The Doll Shop Downstairs (5 page)

Read The Doll Shop Downstairs Online

Authors: Yona Zeldis McDonough

On the Fourth of July, along with Mama and Papa, we climb up onto the roof to watch the fireworks. Although it is usually forbidden, Papa allows us to bring our special dolls and the tea set up with us. We give the dolls root beer in the cups and broken pretzel sticks on the plates; of course, we do the drinking and eating for them. We tap the cups together in a toast, just like we have seen grown-ups do, and we rub our fingers over the plates to get up every last bit of salt. Above us, the night sky blooms with glittering streaks of red, blue, and gold.

By the end of July, we are all tired of the heat. One Sunday we take the streetcar to Coney Island, where we splash in the waves and eat cotton candy on the boardwalk. But most days, we are content to play quietly with the dolls. Sometimes we pretend they are dancers or singers on the stage; other times, they are princesses in a royal court. We use the tea set in almost all our games; Trudie always says how glad she is that we bought it. One day, she accidentally drops a plate and it breaks in two. Her face pales with fear as we both wait for Sophie to explode. But Sophie only says, “If Papa can fix china dolls, I'll bet he can fix china plates, too.”

Trudie is so relieved that she jumps up and hugs Sophie, who looks surprised, but hugs her back.

During the school year, Papa always gets up early and goes to the newsstand on the corner to get his newspaper. In the summer, though, it is my job to get the paper for him. I don't mind at all; getting the paper is kind of fun. Solly, the man at the newsstand, usually rolls the paper into a cone and hands it to me with a bow, like it's a bunch of flowers. Sometimes he even gives me a piece of penny candyâa peppermint ball or a lemon dropâand I get to eat it on the way home.

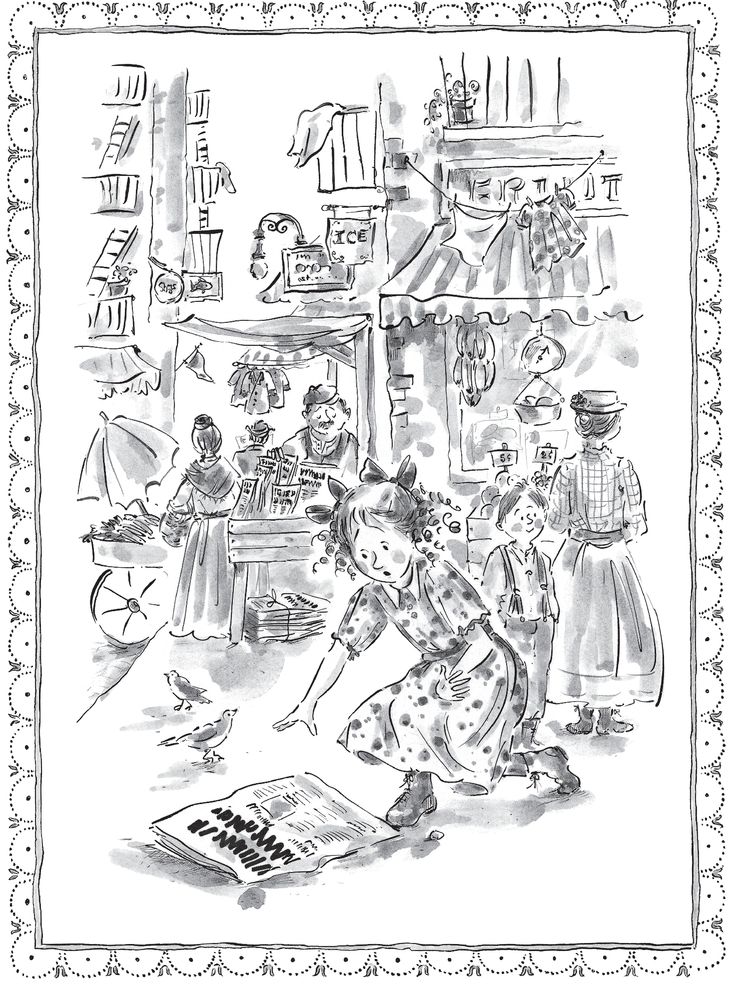

But on the morning of August second, I go to the newsstand and Solly doesn't even seem to know who I am. He just hands me the paper in an absentminded sort of way, and if I didn't tell him twice, he would have forgotten to take my money. I look longingly at the rock candy, the gumdrops, and licorice but Solly doesn't pay any attention. I check my pocketâsometimes I have a penny tucked insideâbut no such luck. I sigh and walk home slowly in the heat, paper tucked under my arm. Then I see it: a penny on the sidewalk, winking up at me. A penny! Now I can run back to Solly's and buy candy after all. As I kneel down to get the penny, I drop the paper, which flops open. The headline is in huge letters:

GERMANY DECLARES WAR ON RUSSIA

FEAR THAT FRANCE IS NEXT

FEAR THAT FRANCE IS NEXT

I have never seen such big letters on a newspaper before. This must be important. Very important. I forget about going back to Solly's for candy and instead run the rest of the way home and take the stairs two at a time. By the time I reach our door, I am out of breath and panting a little. Everyone is at the breakfast table. Sophie is dipping her bread into her tea, and Trudie is taking advantage of Mama's turned back to stick her spoon into the jam jar. I hand Papa the newspaper. I see his eyes get wide and his mouth shrink to a tight, worried line. Silently Papa hands it to Mama. She looks at the headline and then pushes the paper away. “So it's finally come,” Papa says quietly. Mama doesn't reply.

“What's come? What's happened?” says Trudie. There is a dot of jam on her chin.

“The war,” Papa answers.

“What war, Papa?” asks Sophie.

“In Europe,” he explains. “Germany and Russia are fighting .”

“Will it come here?” I ask. I sit down at my place, next to Sophie. To my surprise, she grabs my hand and squeezes it tightly before letting go. Mama has placed a slice of jam-covered bread on my plate, but I suddenly seem to have lost my appetite.

“I don't think so,” Papa says. “But the Germans will invade France, tooâthat much is clear. And we have family in Russia: Mama's brothers and sister, my two brothers. You girls have a lot of cousins you've never even met.”

“I don't want them to get hurt, Mama,” Trudie says.

“We don't want anyone to get hurt,” Mama says, more to herself than to Trudie.

Trudie looks at Mama, and her bottom lip quivers. But before she can actually begin crying, I reach over and touch her on the shoulder. “Don't be scared,” I tell her, trying to sound calm. It isn't easy; I am scared, too. “Everything will be all right.” Will it? I don't really know, but it is the only thing I can think of to say. Trudie's lip stops quivering as she gets up from the table, walks over to me, and plops down in my lap. I let out a loud, showy sigh. But secretly, I am glad. Ever since that day at F.A.O. Schwartz, things have been different with Trudie and me. It's as if now she looks up to me, too, not just Sophie. “Just don't get any jam on me,” I tell her. She nods and then uses my napkin to wipe her face.

Despite the news about the war, everything seems to be normal for the next few weeks. Summer vacation will be over soon. Sophie, Trudie, and I spend our time helping Mama, playing in the doll shop, or trying to stay cool in the stifling heat. Sophie and I take turns putting each other's hair up, and we both comb and style Trudie's hairâanything to get it off our necks. But one night, after dinner, Papa asks us to join him in the parlor. He looks so serious that my heart starts to thump a little faster as we follow him in.

“You all know about the war,” Papa begins.

“We do, Papa,” says Sophie.

“Well, even though America is not fighting, the war will still affect us here.”

“How, Papa?” I ask.

“Doll parts,” he says. “The parts we use come from Germany. And because of the war, we won't be able to get them. Not for a long time, anyway.”

“Why not?” asks Trudie.

“Because America is going to stop trading with Germany. That's what happens when countries go to war. Everything suffers.”

There is a long, heavy silence while we try to make sense of what he has just said.

“How can you fix the dolls without the parts, Papa?” Trudie finally asks.

“I can't,” says Papa. “At least, I can't repair any dolls whose parts I don't have here already.”

“How many dolls is that?” Sophie asks. I glance over at her worried face.

“I'm not sure,” he says. “I'll have to check.”

“If you and Mama can't fix dolls, what will happen to the shop? And what will happen to us?” asks Sophie. Those are the exact questions I want to ask, but I am afraid to hear the answers.

“I'm not sure,” Papa says again, looking down at his hands as if he doesn't quite know what to do with them anymore.

It turns out that there are twenty-three dolls in the shop. For the next week, Papa and Mama work extra hard to fix all the ones whose parts are thereâthat totals ten. When they are done, the mended dolls are picked up or sent back to their homes. Thirteen dolls are left stranded.

Papa takes out a box of file cards. The cards have the names and addresses of the dolls' owners printed in black ink. Papa and Mama write notes to each of the owners, asking what to do with the dolls. Some of the owners come into the shop and take their broken dolls home. I think the dolls seem sad to be leaving before they have been made whole again. Some owners who live in far-off places like New Jersey or Connecticut ask that Papa mail back their dolls, which he does, packing them carefully in double boxes and lots of straw. In the end, there are six dolls left in the shop: Angelica Grace, Victoria Marie, and Bernadette Louise are among them.

“How odd that they all stayed,” says Sophie. Papa has just left for the post office with the last of the dolls to be mailed, Mama is upstairs, and we girls are in the doll shop. With so many of the dolls gone, the shop looks empty and unfamiliar.

“It's like they wer meant for us,” I say.

“Wouldn't it be wonderful if it were true?” asks Sophie.

“If only we could keep them ...” says Trudie, looking deep into Angelica Grace's face. I touch my finger to the crack in Bernadette Marie's glazed white arm but say nothing more.

We stop going down to the doll shop to play. Instead, we try extra hard to help Mama. She has started taking in sewing for some of our neighbors, like Mrs. Kornblatt and Mrs. Mirsky, who live upstairs, and Mrs. Rogoff, who is my friend Esther's mother. Soon our apartment is filled with baskets of clothes to be mended or altered. I overhear Papa and Mama arguing in Yiddish. I hear one wordâ

gelt

âover and over again, so I ask Sophie what it means. She tells me it means

money

.

gelt

âover and over again, so I ask Sophie what it means. She tells me it means

money

.

Other books

Zombies Ever After: Sirens of the Zombie Apocalypse, Book 6 by E.E. Isherwood

The Candy Cookbook by Bradley, Alice

Deon Meyer by Dead Before Dying (html)

Volpone and Other Plays by Ben Jonson

Love, Chloe by Alessandra Torre

Being Emerald by Sylvia Ryan

The Figaro Murders by Laura Lebow

Kin by Lili St. Crow

The Alchemist's Pursuit by Dave Duncan