The Doll Shop Downstairs (2 page)

Read The Doll Shop Downstairs Online

Authors: Yona Zeldis McDonough

“I'm having trouble getting the right color eye for this doll,” Papa said, pointing to Angelica Grace. “The blues I find are always wrong.” He frowned slightly. “But I keep trying. One day, I'll find an eye that's a perfect match.”

“And the others?”

“Well, the owners of this doll,” he said, looking at Victoria Marie, “told me they were going on a long trip. No one will be able to pick the doll up for quite a while so there's no rush in fixing her.” He smoothed the doll's tangled hair gently. “Now this doll,” he said, picking up Bernadette Louise and looking into her face, “is very oldâmuch older than the other two. Getting the right parts for her has been very difficult. They don't make legs or arms the way they used to; I keep hoping I'll find the perfect ones. But so far, I haven't.”

Sometimes, Papa can fix a broken part with his file or one of his other tools. But when he can't fix a part, he has to get a new one. He orders them all the way from Germany, where most of the dolls are made. The doll parts arrive in huge boxes brought by the postman, Mr. Greevy.

Sophie, Trudie, and I are always thrilled when a box arrives, and if we are not in school, we stop whatever we are doing to help Papa open and sort through it. Inside, there are doll arms and legs of different sizes and shapes, all packed in straw and shredded paper. There are lots of wigsâblonde, brown, red, black; braids, buns, curls. Doll bodies are in the box, too, and sometimes clothes. Even though Mama could make or repair anything, a customer sometimes requests a special outfit. Once we found a doll-sized fancy gray silk ball gown and matching evening coat. Another time, there was a satin bridal dress with a train, veil, and the most adorable tiny white leather gloves.

But the very best things in the box are the glass eyes. Because they are so fragile, the eyes are packed first in tissue, then straw, and then finally in their own tiny boxes. Each glass eye is a hollow white ball with a different color in the center. Some are dark, inky blue, while others are sky blue, chocolate brown, amber, or green.

“I wish our dolls had a bed,” says Trudie now, the whine just beginning to creep into her voice. Sophie, who has found Victoria Marie and is busy trying to smooth out her hair, ignores her. “We need a bed.” Now Trudie really is whining.

I want to shake her. But if I do, I will get in trouble with Mama. So instead, I say, “Guess what? We

have

a bed.”

have

a bed.”

“We do?” Trudie asks, eyes wide. Even Sophie looks interested. “Where is it?”

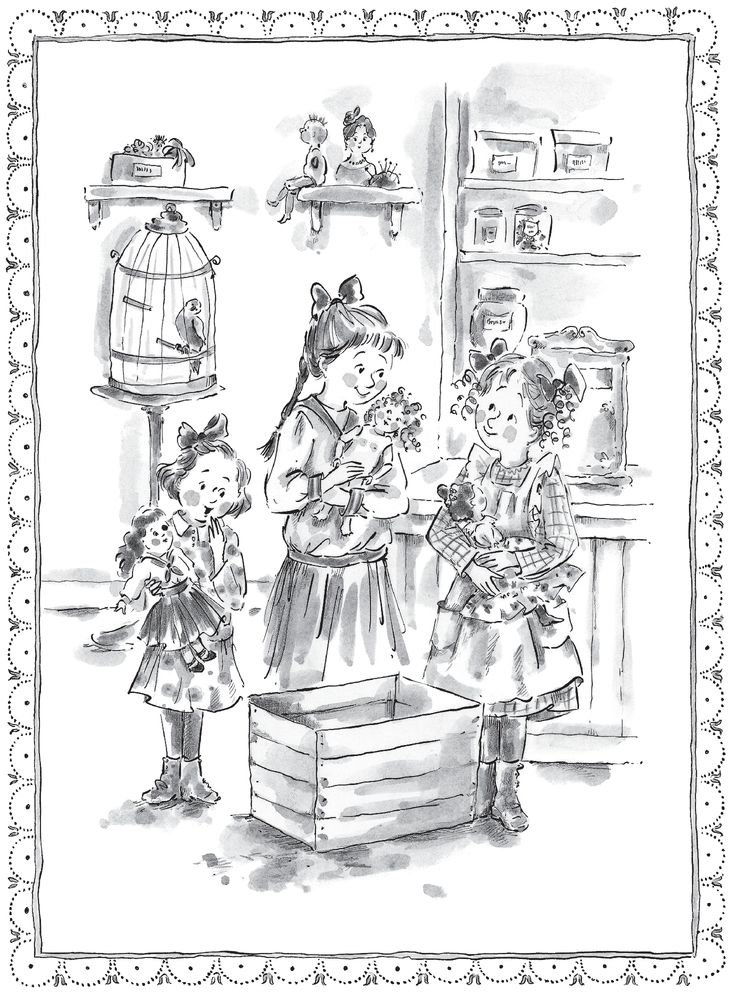

“Right here!” I say, and drag something out from behind the glass-topped counter.

“Oh!” breathes Trudie when she sees it. Of course, if you didn't know, the thing I dragged out might not look much like a bed at all, and instead might seem to be an ordinary wooden box. In fact, it is a box, given to me by Mr. Bloom, who owns the grocery shop on the corner. The box originally held vegetables but now that it was empty, Mr. Bloom was happy to give it to me. Made of smooth golden wood, the box is deep and sturdy. As soon as I saw it, I knew it was a perfect place for three dolls to spend the night.

“That was a good idea, Anna,” Sophie says. I stand up a little straighter when she says that. Even though Sophie can annoy me by being so very perfect, her praise still matters. She doesn't give me much of it, either.

“Go ahead, put her in,” urges Sophie, and Trudie places her doll in the bottom of the box. Sophie and I do the same. Then Trudie bursts out, “But we don't have a blanket! How can they sleep without a blanket?”

“You don't have to cry,” says Sophie. “I have a blanket.”

“Where? Where is it? I want to see!” says Trudie. I'm curious, too. What does Sophie have in mind?

“Here,” Sophie says, and she pulls something white and soft from the pocket of her apron.

“A pillow case!” says Trudie. “How perfect!” She gazes up adoringly at Sophie. “You always know how to fix things,” she adds. Somehow, this makes me feel cross. Trudie didn't get all

that

excited over the bed that I found for us; it's always Sophie this, Sophie that, Sophie, Sophie, Sophie.

that

excited over the bed that I found for us; it's always Sophie this, Sophie that, Sophie, Sophie, Sophie.

“Where did you get it?” I ask.

“From Mama's rag basket,” says Sophie.

Then she tucks the pillowcase up around the dolls' chins.

“Will she mind?”

“No, silly! It's a rag.” Sophie uses that superior, I'm-so-grown-up voice again.

“Can we leave them in the box all night?” asks Trudie, sounding worried.

“Yes,” says Sophie. “They'll be safe. I promise.”

“Good night, Angelica Grace,” says Trudie. She leans over to kiss her doll, loudly, on the cheek.

“Good night,” says Sophie to her own doll as she and Trudie head for the stairs. “Are you coming?” she asks me. Even though she has put the light out, I can feel her looking at me.

“In a minute,” I tell her.

She doesn't say anything else but just takes Trudie's hand and goes upstairs.

I listen to their footsteps as they go, but I don't follow them right away. I want to be alone down here for a little bit. Sometimes it's hard being a middle sister, and I just need to be by myself. Sophie is smart and pretty and good at so many things; Trudie (her real name is Gertrude, though we never call her that) is little and cute and cries to get her way. I'm just the one sort of stuffed in betweenâat nine I'm not old enough to do some things, like light the kitchen stove, but too old to do others, like snuggle in Mama and Papa's bed on a cold morning.

I can hear the sounds of my family moving around above me. In a minute, I know Mama will be calling me to come up. There is a narrow stairway leading up to our apartment, which has four small rooms. Mama does her best to keep our home cheerful and comfortable. “It may not be fancy,” she likes to say, “but it can still be fine.”

She painted our kitchen a color she calls Persian blue, and she grows red geraniums in wooden window boxes. She calls them her “windowsill garden.” In the center of the room is a big table where we eat, and after the dishes are cleared, we do our lessons. The parlor, which is pale peach, has a small settee and two armchairs. Mama keeps a standing lamp between the chairs, so that in the evenings, Papa can read his paper while she does her sewing. Mama and Papa's bedroom is painted mint green. Mama crocheted a white coverlet for the bed, and she made lace trim for the muslin curtains that hang in the windows. The room Sophie, Trudie, and I share is pale pink. The color looks like the inside of a seashell. The apartment has only one sink, which is in the kitchen, and the bathtub is there, too, covered by a hinged white wooden top that can be raised when the tub is in use and lowered when it isn't. Papa designed and made that. The toilet is out in the hall and we have to share it.

I like our apartment, even if it is kind of small. And I love the doll shop. Because I love it, I almost never mind helping with the weekly cleaning. Sophie, Trudie, and I take turns sweeping, wiping the counters and shelves, and polishing the big plate-glass window and the countertop with a rag dipped in sudsy ammonia water. Then we each have our own special chore: Sophie organizes the doll parts, Trudie dusts the dolls with a big feather duster, and I am in charge of the birdcage. Papa has a canary for company while he works, and I am the one to keep the cage fresh and tidy. The canary is named Goldie, because of his color, and he sings all day long. At night, I usually put an old dish towel over the cage, but today I forgot. When I make my way over to the cage in the dark, I see Goldie hopping back and forth from one perch to another.

“Are you lonely down here by yourself?” I ask him. Goldie stops and cocks his little head, as if he is listening to me. Then he starts hopping again. I pick up the dish towel and cover the cage. I look over at my doll, which is snuggled in the box-that-is-a-bed with the other dolls. “You can keep him company,” I tell Bernadette Louise. And somehow, I know she will.

2

S

CHOOL DAYS

CHOOL DAYS

The next few days are very busy, and we have no time to play in the doll shop. Sophie and I both have arithmetic examinations at school. For me, that means I must work extra hard. I enjoy some of my lessons, like reading. Even though I'm two years younger than Sophie, I can read almost all the books she can. And I'm good at history and geography, too. I can easily memorize the names of all the presidents and the state capitals. But arithmetic makes my head pound and my palms sweat. When I see a whole page of figures I have to add or subtract, I feel like I can't breathe. Multiplication is even worse. I practice the times tables at breakfast, on the way to school, while I am getting ready for bed. “Seven times seven is forty-nine,” I say softly. “Seven times eight is fifty-six....” But they are still all fuzzy in my mind.

Coming home from school on Wednesdayâthe day before the examinationsâI tell Sophie I am worried. She seems impatient. “Well, you just have to memorize the times tables.”

“I know.” I wish she could be a little more sympathetic. “I'm trying.”

“You'd better try harder,” is Sophie's reply. “You don't want to get a D, do you?”

“Of course not,” I say. What I do not say is that I am afraid I will get an F, not even a D.

Trudie picks up on my fear and starts teasing meâ“Anna's getting an F, Anna's getting an F”âwhich makes me feel even worse.

But though I am worried about the examination, I don't want to tell Mama and Papa; they have enough to think about right now. Although it's early April, the weather has been blustery, and Papa has come down with a bad cold. Now he's behind with his repair work in the shop. We have to help out with some of Mama's chores upstairs, while Mama does what she can with the doll repair. I have been washing the dishes, changing the sheets, and sweeping the floor, along with trying to memorize those miserable times tables.

On Thursday morning, I pick at my pumpernickel bread and jam; everyone else is too busy to even notice that I hardly eat a thing. Sophie and Trudie walk ahead of me on the way to school. I lag behind, not at all eager to arrive. Here's Guttman's Pickle Shop, where Mama gets the crunchy pickles we all love; there's Zeitlin's Bakery, where they make the most delicious cinnamon buns. Down one street is the

shul

where we all go for services on Saturdays; down another is an empty lot where we sometimes play when the weather is warm. Other kids from the neighborhood join us: we play tag and stickball, and we jump rope. I wish I could go there now. In fact, I wish I could go anywhere other than where I am going now.

shul

where we all go for services on Saturdays; down another is an empty lot where we sometimes play when the weather is warm. Other kids from the neighborhood join us: we play tag and stickball, and we jump rope. I wish I could go there now. In fact, I wish I could go anywhere other than where I am going now.

When I eventually get to school, my sisters are nowhere to be seen. Sophie must have gone up to her sixth-grade classroom. Trudie is in the second grade. I slip into my seat in fourth grade just seconds before we are about to start the day. I'm lucky the teacher, Miss Morrison, is busy at her desk and doesn't mark me late. Three late marks and you have to stay after school. I already have two.

Quickly I unpack my books into my desk. Then I stand with my hand over my heart when it is time to say the Pledge of Allegiance. Miss Morrison hands out paper and tells us to take out our pencils. I tremble a little when she calls out, “Nine times seven,” but then I take some deep breaths to calm myself and think, hard, about what the answer isâsixty-three. Soon the examination is over. What a relief! When it's time for recess in the yard, I run and skip with Batya and Esther, my two best friends in class. At lunch, I take out the brown paper bag Mama has packed for me: rye bread spread with horseradish, a cold boiled potato, and an apple. I won't know what I got on the examination until tomorrow, so I don't have to worry about it until then. When we get home, we find that Papa is feeling better and is back at work in the shop. We are all grateful for that.

The next day, I get my examination back. There is a big red “B” on the top of the paper. B is not a bad grade, especially when I thought I might get an F. That night, when we welcome Shabbos together, everyone seems happy, like it is a party. Mama makes brisket with carrots and onions, and for dessert, there is spice cake.

Other books

Rush of Blood by Billingham, Mark

Fresh Ice by Bradley, Sarah J.

Sean's Sweetheart by Allie Kincheloe

04 - Shock and Awesome by Camilla Chafer

Hush Hush #2 by Anneliese Vandell

Philip and the Angel (9781452416144) by Paulits, John

Dune. La casa Harkonnen by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson

Up All Night-nook by Lyric James

Bear by Ellen Miles

Blood of an Ancient by Rinda Elliott