The Eagle's Vengeance (49 page)

Read The Eagle's Vengeance Online

Authors: Anthony Riches

Tags: #Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Historical, #War & Military

This decision was almost certainly made by the same emperor who had ordered the move north in the first place, Antoninus Pius, as he approached the end of his reign in the late 150s. Ironically, it is quite possible that one of his advisors (for he is known to have been assiduous in seeking counsel before making the big decisions) may have been Lollicus Urbicus, the man who built the new wall on the Forth-Clyde line for him and who was by now prefect of the city of Rome. It seems from archaeological evidence that the army in Britannia, both legionary and auxiliary, was becoming stretched as men were sent elsewhere in the empire to bolster other frontiers. And the praetorian prefect, a major influence in military affairs, had just retired after twenty years, which in turn may have cleared the way for a thorough and probably long-overdue review of troop commitments.

Given that the initial decision to deploy the army further north had been made mainly for political reasons, it feels likely that the men who formulated Rome’s military strategy would have welcomed the decision to move south again, and that after twenty years of existence the revised northern frontier would no longer have represented new and therefore inviolable imperial policy. After all, Antoninus Pius had already enjoyed the acclamation of senate and people for defeating the northern tribes and taking their land, and there was little more to be gained from keeping that ground, given the paucity of any desirable resources such as gold or lead to be exploited. In purely financial terms the balance sheet on the revised northern frontier in Britannia simply did not add up by comparison to the way in which a province like Dacia could be seen to provide financial benefit to the empire through its abundance of precious metals. After so long on the throne, and with no obvious challenge to his rule, Antoninus Pius would probably have been perfectly relaxed about the apparent benefits of shortening the army’s lines of supply, and pulling back to a line of defence that, with the benefit of experience, was deemed to be more suitable for the long term.

And so the army destroyed what it could, buried what could not be burned or carted away and conducted a controlled withdrawal to the south, reoccupying Hadrian’s Wall and reinstating the previous buffer zone to the old wall’s north through its control of the Selgovae and Votadini kingdoms. The Antonine line may have been reoccupied, with the military expedition into Scotland in

AD

208–210 as the most likely occasion for some refurbishment (and don’t worry, readers, we’ll be there with Marcus Valerius Aquila alongside the emperor Septimius Severus and his warring sons in the fullness of time), but there is no definitive evidence for any such re-occupation. The wall was left to a slow deterioration, its forts destroyed but its major features, the turf wall and ditch, left intact to slowly slide into ruin over the course of the next two millennia.

If you want to know more about this under-regarded piece of ancient history on our doorstep, so to speak, I heartily recommend David Breeze’s excellent

The Antonine Wall

. As with his work on Hadrian’s Wall written with Brian Dobson, he has distilled pretty much everything worth knowing about the subject into an accessible and engrossing book which informs the reader without ever patronising.

One last (but, as before with this issue, important) point, that of place naming. Not very much is known about the names that were given to the wall forts along this short-lived imperial frontier, mainly due to the fact that by contrast with Hadrian’s Wall, which was manned for almost three hundred years, the Antonine Wall’s existence was fleetingly brief. We have two main sources of information in this respect, the

Notitia Dignitatum

(literally a List of the Dignitaries), a record of the empire’s official posts and military units at the end of the 4th century, and the

Ravenna Cosmography

, a list of all towns and road stations throughout the Roman empire which was compiled from a variety of maps in about

AD

700 by an anonymous monk in Ravenna. Whilst the former is a contemporaneous review of the empire it was carried out two hundred years after the wall was abandoned for the last time, while the latter relied on cartographic material no less than five hundred years after that final occupation – which makes it unsurprising that neither provide us with very much help as to what the forts were actually called by the Romans.

Given this absence of any meaningful information I have been forced to use my imagination in coming up with two of the three fort names used, while one is more probable than definite in its provenance. ‘Broad View Fort’, modern day Mumrills, was, it is hypothesised, probably Volitanio, the ‘rather broad place’. ‘Lazy Hill’, modern day Falkirk, is my own invention in the absence of anything more concrete, as is the use of the name ‘Gateway Fort’ for modern day Camelon. The name felt appropriate for an outpost which, being too close to the wall to offer any significant early warning of an attack from the north, has the look of a customs and border control point.

As usual, any and all errors in these and other historical interpretations are all my own work!

THE ROMAN ARMY IN 182 AD

By the late second century, the point at which the

Empire

series begins, the Imperial Roman Army had long since evolved into a stable organization with a stable

modus operandi

. Thirty or so

legions

(there’s still some debate about the 9th Legion’s fate), each with an official strength of 5,500 legionaries, formed the army’s 165,000-man heavy infantry backbone, while 360 or so

auxiliary

cohorts

(each of them the equivalent of a 600-man infantry battalion) provided another 217,000 soldiers for the empire’s defence.

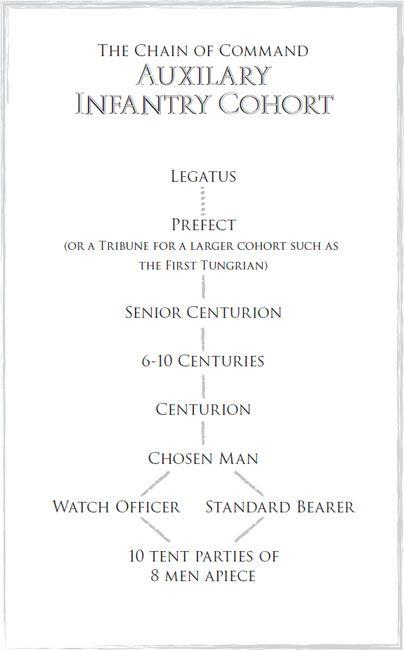

Positioned mainly in the empire’s border provinces, these forces performed two main tasks. Whilst ostensibly providing a strong means of defence against external attack, their role was just as much about maintaining Roman rule in the most challenging of the empire’s subject territories. It was no coincidence that the troublesome provinces of Britain and Dacia were deemed to require 60 and 44 auxiliary cohorts respectively, almost a quarter of the total available. It should be noted, however, that whilst their overall strategic task was the same, the terms under the two halves of the army served were quite different.

The legions, the primary Roman military unit for conducting warfare at the operational or theatre level, had been in existence since early in the Republic, hundreds of years before. They were composed mainly of close-order heavy infantry, well-drilled and highly motivated, recruited on a professional basis and, critically to an understanding of their place in Roman society, manned by soldiers who were Roman citizens. The jobless poor were thus provided with a route to both citizenship and a valuable trade, since service with the legions was as much about construction – fortresses, roads, and even major defensive works such as Hadrian’s Wall – as destruction. Vitally for the maintenance of the empire’s borders, this attractiveness of service made a large standing field army a possibility, and allowed for both the control and defence of the conquered territories.

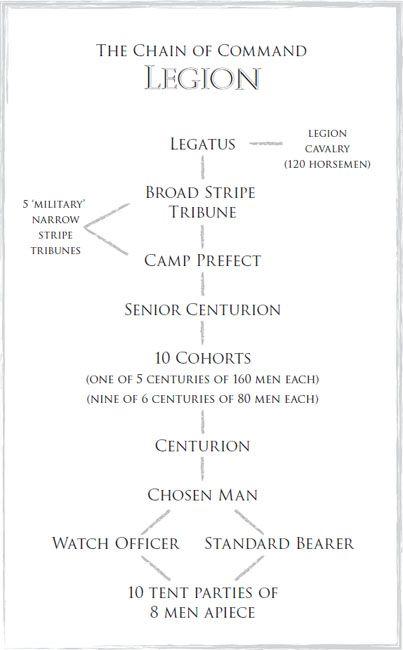

By this point in Britannia’s history three legions were positioned to control the restive peoples both beyond and behind the province’s borders. These were the 2nd, based in South Wales, the 20th, watching North Wales, and the 6th, positioned to the east of the Pennine range and ready to respond to any trouble on the northern frontier. Each of these legions was commanded by a

legatus

, an experienced man of senatorial rank deemed worthy of the responsibility and appointed by the emperor. The command structure beneath the legatus was a delicate balance, combining the requirement for training and advancing Rome’s young aristocrats for their future roles with the necessity for the legion to be led into battle by experienced and hardened officers.

Directly beneath the legatus were a half-dozen or so

military tribunes

, one of them a young man of the senatorial class called the

broad stripe tribune

after the broad senatorial stripe on his tunic. This relatively inexperienced man – it would have been his first official position – acted as the legion’s second-in-command, despite being a relatively tender age when compared with the men around him. The remainder of the military tribunes were

narrow stripes

, men of the equestrian class who usually already had some command experience under their belts from leading an auxiliary cohort. Intriguingly, since the more experienced narrow-stripe tribunes effectively reported to the broad stripe, such a reversal of the usual military conventions around fitness for command must have made for some interesting man-management situations. The legion’s third in command was the camp

prefect

, an older and more experienced soldier, usually a former centurion deemed worthy of one last role in the legion’s service before retirement, usually for one year. He would by necessity have been a steady hand, operating as the voice of experience in advising the legion’s senior officers as to the realities of warfare and the management of the legion’s soldiers.

Reporting into this command structure were ten

cohorts

of soldiers, each one composed of a number of eighty-man

centuries

. Each century was a collection of ten

tent parties

– eight men who literally shared a tent when out in the field. Nine of the cohorts had six centuries, and an establishment strength of 480 men, whilst the prestigious

first cohort

, commanded by the legion’s

senior centurion

, was composed of five double-strength centuries and therefore fielded 800 soldiers when fully manned. This organization provided the legion with its cutting edge: 5,000 or so well-trained heavy infantrymen operating in regiment and company sized units, and led by battle-hardened officers, the legion’s centurions, men whose position was usually achieved by dint of their demonstrated leadership skills.

The rank of

centurion

was pretty much the peak of achievement for an ambitious soldier, commanding an eighty-man century and paid ten times as much as the men each officer commanded. Whilst the majority of centurions were promoted from the ranks, some were appointed from above as a result of patronage, or as a result of having completed their service in the

Praetorian Guard

, which had a shorter period of service than the legions. That these externally imposed centurions would have undergone their very own ‘sink or swim’ moment in dealing with their new colleagues is an unavoidable conclusion, for the role was one that by necessity led from the front, and as a result suffered disproportionate casualties. This makes it highly likely that any such appointee felt unlikely to make the grade in action would have received very short shrift from his brother officers.

A small but necessarily effective team reported to the centurion. The

optio

, literally ‘best’ or

chosen man

, was his second-in-command, and stood behind the century in action with a long brass-knobbed stick, literally pushing the soldiers into the fight should the need arise. This seems to have been a remarkably efficient way of managing a large body of men, given the centurion’s place alongside rather than behind his soldiers, and the optio would have been a cool head, paid twice the usual soldier’s wage and a candidate for promotion to centurion if he performed well. The century’s third-in-command was the

tesserarius

or

watch officer

, ostensibly charged with ensuring that sentries were posted and that everyone know the watch word for the day, but also likely to have been responsible for the profusion of tasks such as checking the soldiers’ weapons and equipment, ensuring the maintenance of discipline and so on, that have occupied the lives of junior non-commissioned officers throughout history in delivering a combat-effective unit to their officer. The last member of the centurion’s team was the century’s

signifer

, the

standard bearer

, who both provided a rallying point for the soldiers and helped the centurion by transmitting marching orders to them through movements of his standard. Interestingly, he also functioned as the century’s banker, dealing with the soldiers’ financial affairs. While a soldier caught in the horror of battle might have thought twice about defending his unit’s standard, he might well also have felt a stronger attachment to the man who managed his money for him!