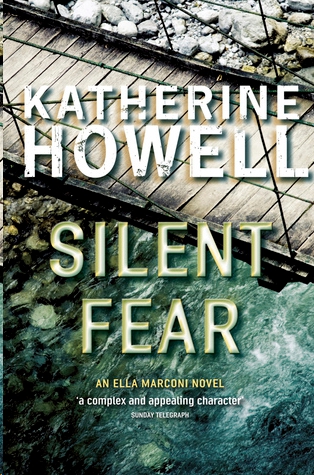

Silent Fear

Authors: Katherine Howell

On a searing summer’s day paramedic Holly Garland rushes to an emergency to find a man collapsed with a bullet wound in the back of his head, CPR being performed by two bystanders, and her long-estranged brother Seth watching it all unfold.

Seth claims to be the dying man’s best friend, but Holly knows better than to believe anything he says and fears that his reappearance will reveal the bleak secrets of her past—secrets which both her fiancé Norris and her colleagues have no idea exist, and which if exposed could cause her to lose everything.

Detective Ella Marconi suspects Seth too, but she’s also sure the dead man’s wife is lying, and the deceased’s boss seems just too helpful. But then a shocking double homicide makes Ella realise that her investigations are getting closer to the killer, but also increasing the risk of an even higher body count.

CONTENTS

For Benette

ONE

T

he radio crackled. ‘Thirty-two.’ Paramedic Holly Garland grabbed the microphone off the ambulance dash. ‘Thirty-two’s on Missenden Road near King Street in Newtown.’

‘Thanks, Two,’ Control said. ‘Head to Beaman Park in Vera Avenue in Earlwood, cross street is Flinders. Twenty-nine-year-old male collapsed while playing touch. Call-taker’s giving CPR instructions. You’re the closest but I’m searching for backup.’

‘Two’s on the case.’ Holly rehooked the mike, her heart already increasing its pace.

They were three cars back from a red light, traffic packed in around them on every side. The cars on King Street were a solid line across the intersection. She looked at her shift partner, Joe Vandermeer, sitting up straight with both hands on the wheel, his black sunglasses pushed up hard on his face. She’d worked with him only a couple of times before. He put his hand on the switches for the lights and siren. In traffic like this, with no room at all for anyone to move, you sometimes just had to wait until a space opened up, but Holly guessed he was thinking what was in her mind too: a cardiac arrest. In a twenty-nine-year-old.

Joe flipped the switches. Holly saw the driver of the blue Ford in front jerk in his seat, look around, and edge forward a few centimetres. Nobody could go anywhere.

‘Shit,’ Joe said.

Then the southbound lane on the far side of the intersection started to crawl along. Joe punched the horn to change the siren to yelp. People crept their cars forward and tried to squeeze into the next lane. Joe inched along, flashing the high beams. Holly shifted in her seat as if that could help.

‘You know the way?’ she asked.

‘As far as Dulwich Hill.’

The GPS fixed to the dash was broken. She opened the street directory and ran her finger down the route to Earlwood – King Street and Enmore Road, then Stanmore Road and New Canterbury Road, turn off at Wardell, then over the Cooks River. Main shopping streets. She could just imagine the swerving and near-misses that awaited them there, but taking the back streets would be worse – slower, twistier and potentially full of playing kids, especially at this time of year and on a day like this, so hot and bright. It was Saturday, three weeks before Christmas, and every second person seemed to be out and about. She herself wanted to be at home, in the pool to be precise, lolling in the shallow end with a book in one hand and a mojito chilling the other. She bet that was where Norris was, though with the radio and a beer. He’d had an inspection on a unit that morning but he would’ve been home by eleven, half past at the latest. Fine for him to make her take overtime shifts, to claim that his job kept him busy at all hours, but they were short stints, not the ten- or fourteen-hour shifts she had to do. And on a stinker like this. It’d been pushing thirty degrees by 7 am and she’d mused aloud about calling in sick, but he’d started on about their Plan and how every little bit helped and didn’t she want and couldn’t she see, and she’d put up her hands and walked away. Now it had to be close to thirty-five and the heat coming in the window was practically burning her arm though the aircon was cranked all the way up, and ahead of them was a sea of brake lights, and time was ticking away, and if the poor guy really was in cardiac arrest his chances were ticking right away with it.

‘Come on,’ Joe said, edging the ambulance forward.

Holly’s mobile vibrated in her shirt pocket. The screen showed the message envelope and the name Lacey.

Trouble here.

Holly texted back

Wassup?

but got no reply.

Lacey was a roster coordinator in Control and helped out on the boards sometimes. Maybe there was a big prang happening somewhere, or a bushfire – something she wanted them to know about. Though she’d never texted about jobs before.

‘Come

on

,’ Joe said again.

Just as Holly looked up their light turned green, but the northbound cars in King Street sat like they were parked across the intersection, keeping the three cars in front of the ambulance stuck firmly in place.

Ticking, ticking.

Then the cars heading the opposite way down Missenden rolled forward and Joe squeezed into the gap they left. The siren echoed off the buildings. The light turned red but Joe babied the ambulance along and finally they were in the intersection, the whole world of traffic stopped for them. Holly checked left and said ‘Clear’ and raised her hand in thanks to those drivers while Joe swung into the southbound lane of King Street and they were away.

‘Love this city,’ Holly said.

‘It’s too hot to be playing touch.’ Joe bumped the horn to put the siren back to wail.

Holly clipped her trauma pouch onto her belt. ‘Some Christmas for his family.’

Joe accelerated through the bend into Enmore Road, the truck swaying on its wheels on the turn. Jaywalkers scurried out of their way. He slowed at a red at the intersection of Stanmore, and checking left Holly saw waiting cars and on the corner a boy of about five in a Santa hat dancing with his fingers in his ears. ‘Clear.’

Her phone buzzed with another text. Lacey again.

Don’t talk to anyone till you talk to me.

A shiver of anxiety ran down Holly’s spine.

‘Straight on?’ Joe said.

‘Yes.’

There was no time to worry about what might be happening at Control. Joe barrelled into Lewisham and she saw the traffic getting thicker ahead of them.

‘Take the next left into Wardell.’

The siren was loud in the cabin. Some days she didn’t really hear it, it was just background noise, but days like this, when the heat beat down and the job was too far away and people everywhere watched them pass by, she felt conspicuous. And insufficient. They were just two people rushing in a noisy truck.

She pulled on gloves. ‘Think he’ll really be in arrest?’

‘Good luck to him if he is.’

They shot under the railway line. She looked at the directory. ‘First left after the bridge.’

The Cooks River was wide and brown. In the gaps between the shrubs beside the road she could see the grass in Beaman Park was already beige from the heat and lack of rain. It was a wide expanse on which a lone small child pedalled a bicycle in sweeping loops.

‘Spot them?’ Joe said.

‘Go further round.’ She looked at the map as he screeched left on the roundabout into Riverview. ‘Cross street’s Flinders. Go past the laneway there and take the next left at the roundabout.’

Joe tore onward then around the corner. In the dead-end of Flinders Street Holly saw five cars and a motorbike in a small car park. There was play equipment shaded by trees to the right, and more trees and a low building to the left. A man ran waving from behind it and Joe flipped off the lights and siren.

Holly grabbed the microphone. ‘Thirty-two’s on scene.’

‘Thanks, Two, time is eleven fifty-five. Still looking for backup.’

‘Copy.’ She hung up the mike.

Beyond the building lay a brown sports field. Three people stood by a few others on the ground in the centre. She released her seatbelt and jumped out as Joe stamped on the park brake.

The waver was anxious-eyed and in his late twenties. ‘He looks really bad.’ He brushed his fingertips across a big flat mole on his cheek.

Holly pulled the Oxy-Viva and monitor out of the back of the ambulance. ‘What happened?’

‘He just went down. No warning, didn’t say he felt sick or anything. Just was on the ground all of a sudden, completely out of it.’

The air was hot and dry in Holly’s lungs and the grass crunched under her boots as she hurried onto the field, squinting through the glare to the scene. A blond man stood with two others with dark hair, all of them in shorts and T-shirts, watching a fourth man and a woman kneeling by the supine body. The man was doing compressions, the woman mouth-to-mouth. Holly could see even from that distance that they weren’t much good at it – the compressions were too jerky and too shallow, and the head tilt on the victim was extreme, probably so far past the point of opening his airway that it was actually blocking it.

She said to the man beside her, ‘Does he have any health problems?’

‘I don’t think so.’

They reached the group with Joe close behind. Holly glanced at the standing men, getting their measure. She’d been threatened and hit by friends and relatives before and trusted nobody. These men’s faces were white and strained, then she saw something extra in the last. Familiarity. Recognition. She looked away and looked back.

Seth?

‘Hi, Jade,’ he said.

‘Holly,’ she said, a flush starting.

A slight smile crossed his face. ‘My mistake.’

She turned her back and knelt by the patient. He appeared younger than twenty-nine. He lay flat on his back, arms and legs sprawled, dirt on his knees, one shoelace undone, his short light brown hair wet with sweat and stuck to his grey face, his eyes half-open in the dead stare Holly knew so well.

The man doing compressions counted loudly, ‘Twenty-eight, twenty-nine, thirty and breathe.’ He was stocky and balding. He wore khaki shorts and a white polo shirt with his chest hair showing in the open collar, and he looked frightened. The woman was dressed in black gym pants and a pink singlet and she shook her head to swing her ponytail out of her way as she bent to the victim’s face, pinched his nose and blew two breaths into his mouth. The chest hardly rose.

Holly unpacked her kit. ‘Bring his head back in more of a normal alignment. It’s too far back and that’s why the air’s not going in. And slower there with the compressions. You want a hundred a minute, and a bit deeper. No, don’t stop.’

She set up the tube kit and the Laerdal bag. Joe set up the monitor and got out the leads. The compressor reached thirty again and the woman fumbled with the victim’s head. A bumbag stuck up above her waist.

‘Keep going,’ Holly said. ‘You’re doing all right, just need a bit of finessing.’

‘Sorry,’ the woman whispered.

Holly measured the victim’s neck with her eyes then chose an eight-millimetre tube. ‘Did he still have a pulse when you got to him?’

‘I don’t think so,’ the woman said.

Joe reached around the compressor’s hands to cut the front of the victim’s white T-shirt from hem to collar, then attached monitoring dots to his skin. He shielded the monitor screen from the sun with his hand. ‘Asystole.’

Holly knelt at the victim’s head with the open laryngoscope, her hands sweaty inside her gloves, the sun hot on her back. ‘Stop for a sec.’

The woman let go of the victim’s head. Holly opened his mouth with her left hand. The light shone down the laryngoscope’s blade and lit his pharynx but she couldn’t see the vocal cords.

‘What’s his name?’ Joe asked.

‘Paul Fowler.’ Holly recognised Seth’s voice. ‘He’s got a little girl.’

Shit.

She released Fowler’s jaw and slid her hand under the back of his neck to change the angle. His skin was slick and she assumed it was with sweat until she went to open his mouth again and saw the darkness on her gloves. Blood.

‘Oh my God,’ the woman said.

Holly felt under his neck again. ‘Did anyone see him get hurt?’

‘No,’ one of the standing men said. ‘Nothing happened. He was doing up his shoe and just fell over.’

Holly slid her fingers carefully along Fowler’s skin.

There.

It felt like . . . She put down the laryngoscope.

Joe stopped taping in the IV line. ‘Okay?’

‘We need to roll him,’ Holly said.

She needed to see it, to check. To be sure. She couldn’t help but glance around.

She got the man and woman to help Joe roll Fowler onto his side, then she scraped aside the blood and matted hair at the back of his neck. The hole was small and round. She’d seen bullet wounds before and had no doubt this was another.

She glanced at Joe. He leaned over to see, then a shadow loomed over them as one of the standing men stepped close.

‘What is it?’

Holly motioned for Joe and the others to roll Fowler onto his back again. ‘Just a little wound.’

‘From what?’ the man said, his voice rising. ‘What’s going on?’

Joe got up and moved away to covertly call the police on the portable radio. Holly glanced around the park, then looked up at the man who’d spoken. He had a thin face and short blond hair. His blue T-shirt and shorts said Nike in different-sized** lettering. He shielded his face from the sun as he looked down at her and she saw tears in his eyes.

‘An old cut,’ she said. ‘I knocked the scab off and it started to bleed.’

Dead men didn’t bleed like that but hopefully none of them knew that. The cops would want to speak to everyone who was here. Knowing Seth, there was a lot more to this situation than there appeared and she couldn’t risk them all rushing off to get revenge on whoever they thought was responsible, nor did she want them to start shouting and maybe getting violent.

‘It looked a bit like a bullet wound,’ the man doing compressions said.

‘Oh my God,’ the woman said again. ‘Someone shot him?’

Holly glared at the man. ‘It was a scab.’

‘I never saw a scab on his neck.’ The guy with the mole clenched his fists.

‘It can’t be a bullet wound,’ Seth said. ‘We were all right here and we heard nothing.’

‘You never heard of a silencer?’ the guy with the mole said.

‘It’s a scab,’ Holly said.

Joe came back and gave her a nod. He looked at the monitor, then reached for the adrenaline. Still asystole, Holly knew. Cactus. She picked up the laryngoscope with tight fingers. Angry friends. A shooter somewhere. And Seth, the bastard.

The guy with the mole stared around the park. ‘What arsehole would do something like that?’

The blond one shook his head. ‘This is fucked.’

The fourth man stood slump-shouldered and silent next to Seth. He looked younger than the others and had an old bruise and abrasion on his face. Seth pulled him close with an arm around his neck and whispered in his ear.

Holly wiped her forehead on her sleeve. Fowler was pretty much dead – probably had been even before the woman had yanked his head so far back she’d possibly snapped whatever spinal cord he’d had remaining – but Holly still had to be mindful of the wound, and so tilted his head back just a little then opened his mouth again.