The Edge (24 page)

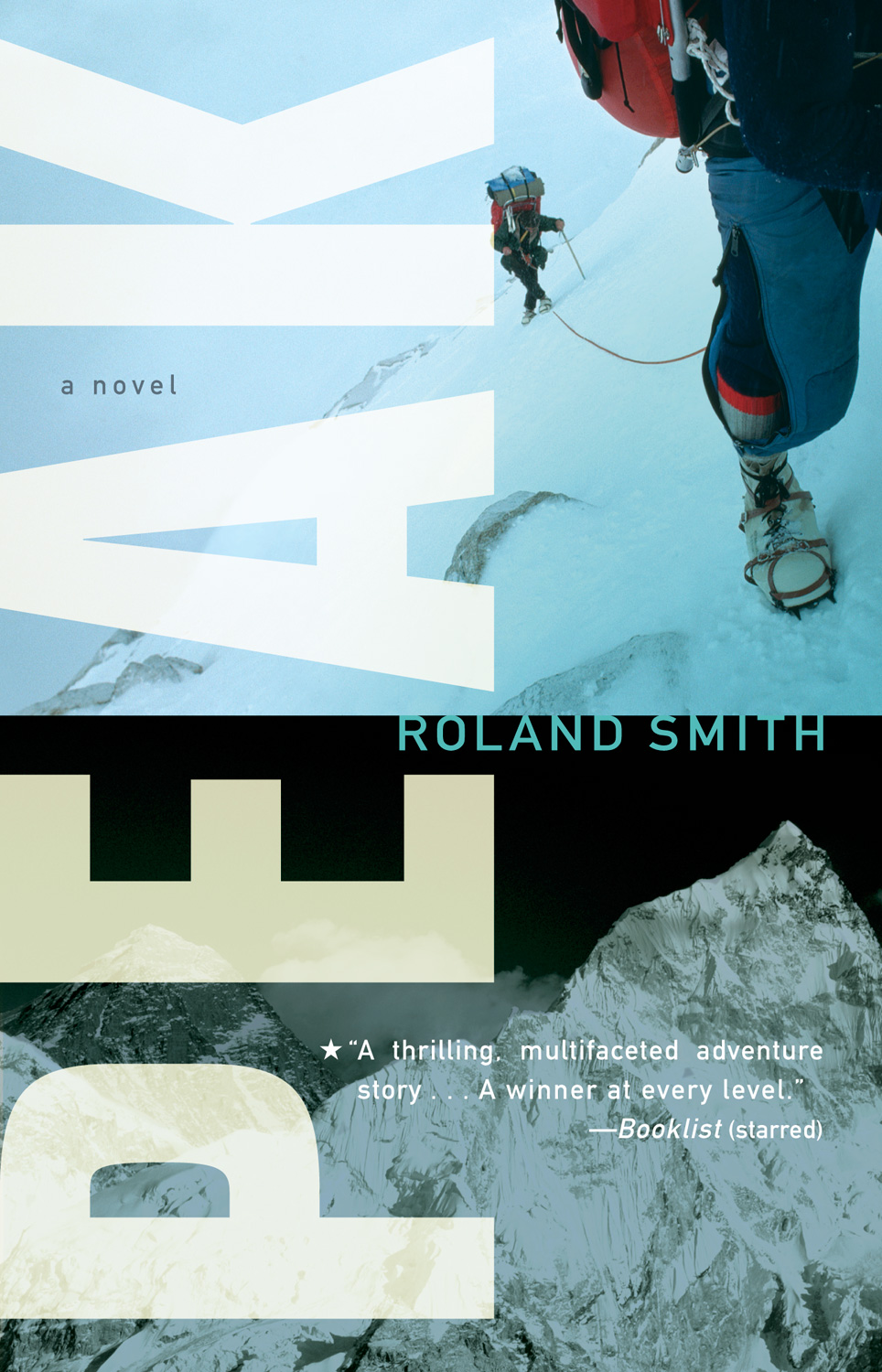

Authors: Roland Smith

He put his hand on my shoulder, looked me in the eye, and said, “You ended the story well.”

But I guess stories never really end.

Alessia comes into the kitchen, where I'm writing.

“The show is starting.”

She and her mother are in New York for the holidays. Alessia is staying with us.

I close the Moleskine journal and follow her into the living room. Rolf and Mom are on the sofa. The two Peas are on the floor with pillows and bowls of popcorn.

“Sit with us, Alessia!” Patrice says.

“Yes, with us!” Paula echoes.

“She doesn't want to lie on the floor,” Mom protests.

“No, no,” Alessia says. “I would love to lie between the two pea pods.”

Patrice turns around just before the documentary starts. “Are we going to the zoo tomorrow to see the

shen

s?”

“Of course,” I answer.

We have gone almost every day since I returned. The cubs are getting big. We watch them playing in the snow.

The Peace Climb begins. No commercials. Just beautiful climbs on different mountains on the same day all over the world. Patrice keeps turning and asking when our climb will appear. They have no idea what happened to us in After Can Stand.

“Soon,” I tell them.

Our climb appears at the very end. It is three minutes long.

“It's a Christmas tree,” Patrice says.

“No it's not,” Paula says. “It's a little mountain. It spells

peace

.”

I look at Mom and Alessia. There are tears in their eyes.

There are tears in my eyes.

The letters do not stand for

peace

, but I wish there were peace.

Aki

Elham     Choma

Phillip             Ebadullah

Books are written in solitude, but published with a great deal of help from hard-working book people. I want to thank Betsy Groban, Scott Magoon, Lisa DiSarro, Hayley Gonnason, and the entire team at HMH, who have stood behind Peak since his climb on Everest in Tibet and now join him on his arduous trek in Afghanistan. Special thanks go to Julie Tibbott who “out of the blue” asked me to write the introduction for the classic Western

Shane

by Jack Schaefer. It was a great honor to be picked to write this introduction, which led me to my old friend, and my fabulous editor, Julia Richardson. If it weren't for Julia, this climb would have never happened.

MY NAME IS PEAK.

Yeah, I know: weird name. But you don't get to pick your name or your parents. (Or a lot of other things in life for that matter.) It could have been worse. My parents could have named me Glacier, or Abyss, or Crampon. I'm not kidding. According to my mom all those names were on the list.

Vincent, my literary mentor (at your school this would be your English teacher), asked me to write this for my year-end assignment (no grades at our school).

When Vincent reads the sentence you just read he'll say:

Peak, that is a run-on sentence and chaotically parenthetical.

(That's how he talks.) Meaning it's a little confusing and choppy. And I'll tell him that my life is (parenthetical) and the chaos is due to the fact that I'm starting this assignment in the back of a Toyota pickup in Tibet (aka China) with an automatic pencil that doesn't have an eraser and it's not likely that I'm going to find an eraser around here.

Vincent has also said that a good writer should draw the reader in by starting in the middle of the story with a

hook,

then go back and fill in what happened before the

hook.

Once you have the reader hooked you can write whatever you want as you slowly reel them in.

I guess Vincent thinks readers are fish. If that's the case, most of Vincent's fish have gotten away. He's written something like twenty literary novels, all of which are out of print. If he knew what he was talking about why do I have to search the dark, moldering aisles of used-book stores to find his books?

(Now I've done it. But remember this, Vincent:

Writers should tell the brutal truth in their own voice and not let individuals, society, or consequences dictate their words!

And you thought no one was listening to you in class. You also know that I really like your books, or I wouldn't waste my time trying to find them. Nor would I be trying to get this story down in the back of a truck in Tibet.)

Speaking of which . . .

This morning we slowed down to get around a boulder the size of a school bus that had fallen in the middle of the road. In the U.S.A. we would use dynamite or heavy equipment to move it. In Tibet they use picks, sledgehammers, and prisoners in tattered, quilted coats to chip the boulder down to nothing. The prisoners smiled at us as we tried not to run over their shackled feet on the narrow road. Their cheerful faces were covered in nicks and cuts from rock shrapnel. Those not chipping used crude wooden wheelbarrows to move the man-made gravel over to potholes, where very old Tibetan prisoners used battered shovels and rakes to fill in the holes. Chinese soldiers in green uniforms and with rifles slung over their shoulders stood around fifty-gallon burn barrels smoking cigarettes. The prisoners looked happier than the soldiers did.

I wondered if the boulder would be gone by the time I came back through. I wondered if I'd ever come back through.

I WAS ONLY TWO-THIRDS

up the wall when the sleet started to freeze onto the black terra-cotta.

My fingers were numb. My nose was running. I didn't have a free hand to wipe my nose, or enough rope to rappel about five hundred feet to the ground. I had planned everything out so carefully, except for the weather, and now it was uh-oh time.

A gust of wind tried to peel me off the wall. I dug my fingers into the seam and hugged the terra-cotta until it passed.

I should have waited until June to make the ascent, but no, moron has to go up in March. Why? Because everything was ready and I have a problem with waiting. I had studied the wall, built all my custom protection, and picked the date. I was ready. And if the date passed I might not try it at all. It doesn't take much to talk yourself out of a stunt like this. That's why there are over six billion people sitting safely inside homes and one . . .

“Moron!” I shouted.

Option #1: Finish the climb. Two hundred sixty-four feet up, or about a hundred precarious fingerholds (providing my fingers didn't break off like icicles).

Option #2: Climb down. A little over five hundred feet, two hundred fifty fingerholds.

Option #3: Wait for rescue. Scratch that option. No one knew I was on the wall. By morning (providing someone actually looked up and saw me) I would be an icy gargoyle. And if I lived my mom would drop me off the wall herself.

Up it is, then.

I timed my moves between vicious blasts of wind, which were becoming more frequent the higher I climbed. The sleet turned to hail, pelting me like a swarm of frozen hornets. But the worst happened about thirty feet from the top, fifteen measly fingerholds away.

I had stopped to give the lactic acid searing my shoulders and arms a chance to simmer down. I was mouth breathing (partly from exertion, partly from terror), and I told myself I would make the final push as soon as I caught my breath.

While I waited, a thick mist drifted in around me. The top of the wall disappeared, which was just as well. When you're tired and scared, thirty feet looks about the length of two football fields, and that can be pretty demoralizing. Scaling a wall happens one foothold and one handhold at a time. Thinking beyond that can weaken your resolve, and it's your will that gets you to the top as much as your muscles and climbing skills.

Finally, I started breathing through my runny nose again. Kind of snorting, really, but I was able to close my mouth every other breath.

This is it,

I told myself.

Fifteen more handholds and I've topped it.

I reached up for the next seam and encountered a little snag. Well, a big snag really . . .

My right ear and cheek were frozen to the wall.

To reach the top you must have resolve, muscles, skill, and . . .

A FACE!

Mine was anchored to that wall like a bolt, and a portion of it stayed there when I gathered enough

resolve

to tear it loose. Now I was mad, which was exactly what I needed to finish the climb.

Cursing with every vertical lunge, I stopped about four feet below the edge, tempted to tag this monster with the blood running down my neck. But instead I took the mountain stencil out of my pack (cheating, I know, but you have to have two free hands to do it freehand), slapped it on the wall, and filled it in with blue spray paint.

This is when the helicopter came up behind me and nearly blew me off the wall.

“You are under arrest!” an amplified voice shouted above the deafening rotors.

I looked down. Most of the mist had been swirled away by the chopper rotors, and for the first time in an hour I could see the busy street eight hundred feet below the skyscraper.

A black rope dropped down next to me, and two alarmed and angry faces leaned over the edge of the roof.

“Take the rope!”

I wasn't about to take the rope four feet away from my goal. I started up.

“Take the rope!”

When my head reached the top of the railing they hauled me up and cuffed my wrists behind my back. They were wearing SWAT gear and NYPD baseball caps, and there were a lot of them.

One of the cops leaned close to my bloody ear. “What were you thinking?” he said, then jerked me to my feet and handed me off to a regular street cop.

“Get this moron to emergency.”

Visit

www.hmhco.com

or your favorite retailer to purchase the book in its entirety.

R

OLAND

S

MITH

is the

author of

Peak

, a best-selling novel that was named an ALA Best Book for Young Adults, a New York Public Library Book for the Teen Age, and a Booklist Editors'

Choice, among other accolades. His other books include

The Captain's Dog,

Jack's Run, Cryptid Hunters, Zach's Lie

, and

Mutation

. He lives on a small farm outside of Portland, Oregon, with his wife, Marie. You can learn more about Roland at

rolandsmith.com

.