The Egypt Code (14 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

I took out a map of the Memphite region showing all the pyramid fields on the west side of the Nile, and on the east side the solar city of Heliopolis from where had emanated, in all probability, the impulse to build all those giant pyramids that were scattered seemingly randomly in the desert. I gazed intently at the location of Heliopolis, then at the Giza pyramids, then at the other pyramid fields further south. There was a ghost hidden in this map. I could feel it, almost see it. Slowly a mist began to lift in my mind and also from the whole Memphite region. Beneath it shimmered a weird starry landscape. Suddenly I knew that I was looking at the ‘Splendid Place of the First Time’ . . .

CHAPTER THREE

The Duat of Memphis

Did the Egyptians of the Pyramid Age have much more astronomical and geographical knowledge than hitherto assumed by us?

George Goyon,

Kheops

:

Le Secret des Batiseurs des Grandes Pyramides

Kheops

:

Le Secret des Batiseurs des Grandes Pyramides

The idea that the distribution of the pyramids is governed by definable ideological (religious, astronomical, or similar) considerations is attractive. After all, if there were such reasons for the design of the pyramid and for the relationship of monuments at one site, why should we shut our eyes to the possibility that similar thinking was behind the apparently almost perverse scatter of the pyramids over the Memphite area? The argument that the Egyptians would not have been able to achieve this had they set their mind to it cannot be seriously entertained.

J. Malek, ‘Orion and the Giza Pyramids’

The founder of the great Fourth Dynasty was the pharaoh Snefru, the son of Djoser. But instead of building a step pyramid like his father at Saqqara, Snefru invented the new design of the ‘true’ or smooth-faced pyramid and built not one but two pyramids seven kilometres south of Saqqara, at a site called Dashur. Oddly enough, the site of Dashur is not on a promontory like Saqqara, nor does it have any special geological features that may have warranted a move so far away from the Step Pyramid. Immediately after Snefru died, his son, the pharaoh Khufu, did the opposite of his father: he moved 12 kilometres

north

of Saqqara, and built his giant pyramid on the high promontory we call the Giza plateau. This curious moving around continued with his son, Djedefra, who decamped another eight kilometres north and built his own pyramid at a place called Abu Ruwash. His two successors, Khafra and Menkaura, returned to Giza and build their pyramids next to Khufu’s. Then the Fifth Dynasty came along. Its first pharaoh, Userkaf, returned to Saqqara and built his pyramid next to Djoser’s Step Pyramid. His six successors, however, all moved north of Saqqara and raised their pyramids at a place called Abusir. Yet the last king of the Fifth Dynasty returned to Saqqara to build his pyramid south of the Step Pyramid of Djoser.

north

of Saqqara, and built his giant pyramid on the high promontory we call the Giza plateau. This curious moving around continued with his son, Djedefra, who decamped another eight kilometres north and built his own pyramid at a place called Abu Ruwash. His two successors, Khafra and Menkaura, returned to Giza and build their pyramids next to Khufu’s. Then the Fifth Dynasty came along. Its first pharaoh, Userkaf, returned to Saqqara and built his pyramid next to Djoser’s Step Pyramid. His six successors, however, all moved north of Saqqara and raised their pyramids at a place called Abusir. Yet the last king of the Fifth Dynasty returned to Saqqara to build his pyramid south of the Step Pyramid of Djoser.

What drove these kings to play musical chairs with their pyramids all over the Memphite region? Take the case of Khufu. The standard explanation is that he chose the Giza plateau because it had a commanding view over the whole Memphite region. But if that was the true motive behind his choice of location, then we may well ask why his father Snefru or, for that matter, his grandfather Djoser, did not grab this prime afterlife site for themselves. Miroslav Verner, the eminent Czech Egyptologist, puzzled over this enigma in another way:

The reasons why the ancient Egyptians buried their dead on the edge of the desert on the western bank of the Nile are evident enough. The same, however, cannot be said of the reasons for their particular choice of sites for pyramid-building. Why, for example, did the founder of the Fourth Dynasty, Snefru, build his first pyramid at Meydum then abandoned the place, building another two of his pyramids approximately 50 kilometres further north of Dashur? Why did his son Khufu build his tomb, the celebrated Great Pyramid, still further to the north in Giza? . . . the questions are numerous, and, as a rule, answers to them remain on the level of conjecture.

1

In 1983 I came up with some conjecture of my own. I wrote to a selection of eminent Egyptologists and suggested to them that the reason for this apparent unruly scattering of pyramids along the 40-kilometre strip of desert they call the Memphite Necropolis had little if anything to do with engineering or geological practicalities, as is often suggested, but rather with religion. To be more specific, I proposed a controversial new idea: that the religious motive was to replicate on the land the scattering of stars that were said to be in the Duat. Not too unexpectedly, I was patronisingly told to mind my own business.

2

In any case, according to Egyptologists the pyramids had nothing or very little to do with the stars, but were symbols of the sun. This ‘solar’ tag was so entrenched in Egyptology that anyone suggesting otherwise, and especially an outsider speaking of a connection with the stars, was bound to be ignored at best or severely pilloried and ridiculed at worst. As for the bizarre random scattering of pyramids in clusters in the open desert, this, virtually all Egyptologists insisted, had nothing to do with imaginary stellar plans (or any plan for that matter), but rather with a pharaoh’s whim to have his pyramid near his palace or because of the discovery of a better supply of limestone. There was, however, no convincing evidence that the pharaohs had palaces at different locations, and as Miroslav Verner argued, ‘limestone occurs almost everywhere in the area of the Memphite necropolis and the technical difficulties in obtaining it and transporting it to the building site did not vary substantially between the different places’.

3

2

In any case, according to Egyptologists the pyramids had nothing or very little to do with the stars, but were symbols of the sun. This ‘solar’ tag was so entrenched in Egyptology that anyone suggesting otherwise, and especially an outsider speaking of a connection with the stars, was bound to be ignored at best or severely pilloried and ridiculed at worst. As for the bizarre random scattering of pyramids in clusters in the open desert, this, virtually all Egyptologists insisted, had nothing to do with imaginary stellar plans (or any plan for that matter), but rather with a pharaoh’s whim to have his pyramid near his palace or because of the discovery of a better supply of limestone. There was, however, no convincing evidence that the pharaohs had palaces at different locations, and as Miroslav Verner argued, ‘limestone occurs almost everywhere in the area of the Memphite necropolis and the technical difficulties in obtaining it and transporting it to the building site did not vary substantially between the different places’.

3

By 1994, however, some second thoughts on the ‘religious’ idea were beginning to be aired. We have seen how the director of the Griffith Institute at Oxford, Dr. Jasomir Malek, after reviewing my book

The Orion Mystery

, felt that ‘the idea that the distribution of the pyramids is governed by definable ideological (religious, astronomical, or similar) considerations is attractive.’

4

The Orion Mystery

, felt that ‘the idea that the distribution of the pyramids is governed by definable ideological (religious, astronomical, or similar) considerations is attractive.’

4

Mark Lehner also relented a little by offering that ‘some religious or cosmic impulse beyond the purely practical may also have influenced the ancient surveyors’, although he remained sceptical about a stellar-based plan.

5

As far as Lehner is concerned, the possible ‘cosmic impulse’ that may have influenced the choice of location for a pyramid site came from the emerging powerful sun-religion of Ra at Heliopolis that had apparently reached its peak in the Fourth Dynasty. His colleague Dr Zahi Hawass even went so far as to claim that Khufu, its second king, demanded to be venerated as Ra on earth-a theory that, for a while at least, gained much support among other Egyptologists. There is, admittedly, much that invites such views. For example, it is true that after Khufu’s death, many of his successors incorporated the name of Ra to their own - Djedefra, Khafra, Menkaura, Sahura and so on. They also took the title ‘Son of Ra’.

6

According to Mark Lehner:

5

As far as Lehner is concerned, the possible ‘cosmic impulse’ that may have influenced the choice of location for a pyramid site came from the emerging powerful sun-religion of Ra at Heliopolis that had apparently reached its peak in the Fourth Dynasty. His colleague Dr Zahi Hawass even went so far as to claim that Khufu, its second king, demanded to be venerated as Ra on earth-a theory that, for a while at least, gained much support among other Egyptologists. There is, admittedly, much that invites such views. For example, it is true that after Khufu’s death, many of his successors incorporated the name of Ra to their own - Djedefra, Khafra, Menkaura, Sahura and so on. They also took the title ‘Son of Ra’.

6

According to Mark Lehner:

. . . the pyramid built by Djededfre, Khufu’s son and successor, [is] 8 kilometre (5 miles) to the north on a hillock overlooking the Giza plateau. By moving to this spot (Abu Roash), Djedefre’s pyramid was nearer due west of Heliopolis, centre of the sun cult, than Giza. Perhaps he was motivated by religious reasons since Djedefre is the first pharaoh to take the title ‘Son of Re’.

7

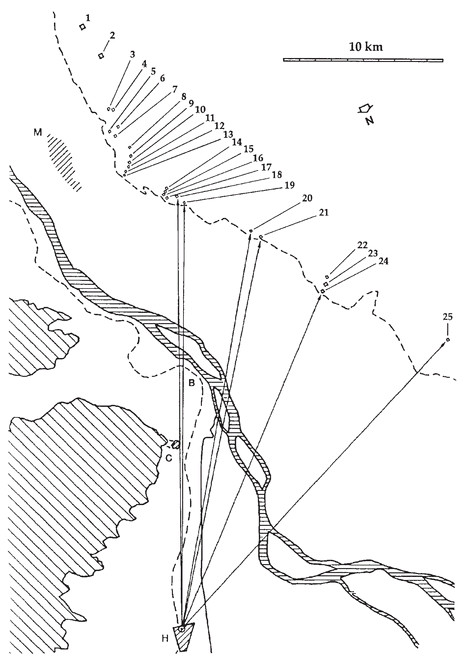

Map of the Memphite Necropolis. 14, 15, 16 and 17 are the Abusir Pyramids. 18 and 19 are the Sun Temples of Abu Ghorab. 22, 23 and 24 are the Giza Pyramids.

Lehner might be right in this supposition. Saying, however, that Djedefra’s pyramid was ‘nearer due west’ of Heliopolis is somewhat off the mark. Measuring from a scaled map of the Memphite Necropolis,

8

it is obvious that Djedefra’s pyramid is nearer 27° south-of-west from Heliopolis. At this latitude this is the orientation of the setting sun at the winter solstice. Alternatively, an observer at Djedefra’s pyramid looking east towards Heliopolis would have seen the sun rising directly over Heliopolis on or very near the day of the summer solstice,

9

which can hardly be taken as a coincidence in these circumstances. The reader will recall from Chapter Two how important the summer solstice was to the feast of the ‘Birth of Ra’, when the civil calendar was inaugurated. At any rate, the transition from the Fourth to the Fifth Dynasty may also have been due to a dynastic

coup d’état

when a priestess called Rudjdjedet, wife of the high priest of Heliopolis, gave birth to triplets which she claimed had been conceived by Ra himself.

10

All three were to become kings. Two of these sun-kings, Sahura and Neferikara, incorporated the name of Ra to their own, and although the third, Userkaf, did not, he nonetheless took the unprecedented step of building a sun temple that was modelled on the great temple of Ra at Heliopolis.

11

The curious thing about Userkaf’s sun temple, however, is that it was not built near his pyramid at Saqqara but at Abu Ghorab, some three kilometres away to the north. Indeed five of the so-called sun-kings of the Fifth Dynasty who followed Userkaf also built temples at Abu Ghorab, even though their pyramids were raised a kilometre or so to the south at Abusir (nearer Saqqara).

12

Until recently no one quite understood why these sun temples were built at all and why, more intriguingly, they were placed away from their corresponding pyramids. Only two of the six have been found by archaeologists - Userkaf’s and Niussera’s. We know of the others only by their names found in contemporary inscriptions: ‘The stronghold of Ra’, ‘The Offering Fields of Ra’, ‘The Favourite Place of Ra’, ‘The Offering Table of Ra’, ‘The Delight of Ra’, and ‘The Horizon of Ra’. This very obvious connection with the sun-god of Heliopolis, however, was not merely spiritual. According to a new theory by British Egyptologist David Jeffreys, it was all about their exact location relative to Heliopolis.

8

it is obvious that Djedefra’s pyramid is nearer 27° south-of-west from Heliopolis. At this latitude this is the orientation of the setting sun at the winter solstice. Alternatively, an observer at Djedefra’s pyramid looking east towards Heliopolis would have seen the sun rising directly over Heliopolis on or very near the day of the summer solstice,

9

which can hardly be taken as a coincidence in these circumstances. The reader will recall from Chapter Two how important the summer solstice was to the feast of the ‘Birth of Ra’, when the civil calendar was inaugurated. At any rate, the transition from the Fourth to the Fifth Dynasty may also have been due to a dynastic

coup d’état

when a priestess called Rudjdjedet, wife of the high priest of Heliopolis, gave birth to triplets which she claimed had been conceived by Ra himself.

10

All three were to become kings. Two of these sun-kings, Sahura and Neferikara, incorporated the name of Ra to their own, and although the third, Userkaf, did not, he nonetheless took the unprecedented step of building a sun temple that was modelled on the great temple of Ra at Heliopolis.

11

The curious thing about Userkaf’s sun temple, however, is that it was not built near his pyramid at Saqqara but at Abu Ghorab, some three kilometres away to the north. Indeed five of the so-called sun-kings of the Fifth Dynasty who followed Userkaf also built temples at Abu Ghorab, even though their pyramids were raised a kilometre or so to the south at Abusir (nearer Saqqara).

12

Until recently no one quite understood why these sun temples were built at all and why, more intriguingly, they were placed away from their corresponding pyramids. Only two of the six have been found by archaeologists - Userkaf’s and Niussera’s. We know of the others only by their names found in contemporary inscriptions: ‘The stronghold of Ra’, ‘The Offering Fields of Ra’, ‘The Favourite Place of Ra’, ‘The Offering Table of Ra’, ‘The Delight of Ra’, and ‘The Horizon of Ra’. This very obvious connection with the sun-god of Heliopolis, however, was not merely spiritual. According to a new theory by British Egyptologist David Jeffreys, it was all about their exact location relative to Heliopolis.

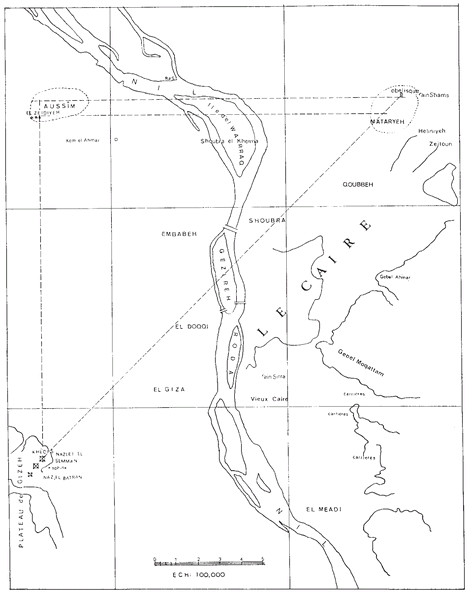

Map of the Giza-Ausim-Heliopolis region

In the late 1990s, Jeffreys was conducting a survey in the area of Memphis on behalf of the Egypt Exploration Society. Armed with the latest topographical maps and good surveying equipment, he was puzzled by the fact that whereas from the sun temples of Userkaf and Niussera he had an unobstructed line of sight to Heliopolis, if he moved just a little further south towards the Abusir pyramids, his view was cut off by the Muqattam hills.

13

In a flash of inspiration Jeffreys realised that perhaps this was the reason why the sun temples were built some distance north of their corresponding pyramids. This also meant, of course, that all the pyramids

north

of Abu Ghorab (which included Zawyat Al Aryan, Giza and Abu Ruwash) also had clear unobstructed views to Heliopolis, whereas those

south

of Abu Ghorab (including Abusir, Saqqara, Dashur and all others up to Meydum) simply did not. It struck him that only the Fourth Dynasty pyramids and Fifth Dynasty sun temples had unobstructed lines of sight to Heliopolis, and that it was these two dynasties that allegedly had special reverence for the sun-god Ra of Heliopolis. In Jeffreys’ own words:

13

In a flash of inspiration Jeffreys realised that perhaps this was the reason why the sun temples were built some distance north of their corresponding pyramids. This also meant, of course, that all the pyramids

north

of Abu Ghorab (which included Zawyat Al Aryan, Giza and Abu Ruwash) also had clear unobstructed views to Heliopolis, whereas those

south

of Abu Ghorab (including Abusir, Saqqara, Dashur and all others up to Meydum) simply did not. It struck him that only the Fourth Dynasty pyramids and Fifth Dynasty sun temples had unobstructed lines of sight to Heliopolis, and that it was these two dynasties that allegedly had special reverence for the sun-god Ra of Heliopolis. In Jeffreys’ own words:

A re-examination of the location of Pyramids whose owners claim or display a special association with the solar cult betrays a cluster pattern for which a political and religious explanation suggests itself . . . The Giza pyramids could also be seen from Heliopolis . . . It is therefore appropriate to ask, in a landscape as prospect-dominated as the Nile Valley, which sites and monuments were mutually visible and whether their respective locations, horizons and vistas are owed to something more than mere coincidence.

14

Other books

The Quiet Game by Greg Iles

Adversaries and Lovers by Watters, Patricia

Courage Tree by Diane Chamberlain

Come, Reza, Ama by Elizabeth Gilbert

The Machine by Joe Posnanski

H.M. Hoover - Lost Star by H. M. Hoover

Sailor & Lula by Barry Gifford

Murder for a Rainy Day (Pecan Bayou Book 6) by Teresa Trent

La sombra del Coyote / El Coyote acorralado by José Mallorquí