The Egypt Code (15 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

At long last here was a prominent and well-respected Egyptologist who was proposing nothing less than ‘a re-examination of the location’ of the pyramids which could account for ‘the oscillation in the location of pyramid sites’ or, in other words, the scattering of pyramid clusters along the 40 kilometre strip of desert which is the Memphite Necropolis. It was nothing short of a major breakthrough. This is because it brought on to the academic table the strong possibility that pyramids - at the very least those with lines of sight to Heliopolis - were interrelated by the same surveying motive, implying a master plan that took into account the vast area encompassed by the Memphite Necropolis and Heliopolis.

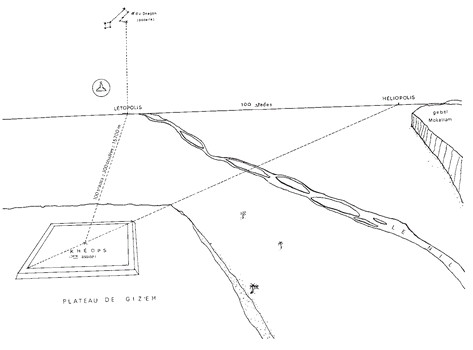

Having worked in the construction industry for many years in the Middle East, often surveying vast areas of open desert for new roads and remote military bases, I knew that a project as vast as that suggested above would require a fixed point or datum from which a topographic survey grid could emanate. The location of this datum point would, ideally, be at the intersection of a prime latitude and a prime meridian that would become the X-Y axes of a huge grid. Since the principal objective of the project would be the positioning of pyramids along a strip of desert running from Abu Ruwash to Abusir, with the added requirement of them having clear lines of sight to Heliopolis, the ideal location for this datum point would be somewhere due west of Heliopolis and due north of Giza. Working with a good map of the region, I easily established that this point would fall within the modern town of Ausim, once called by the Greeks Letopolis and Khem by the ancient Egyptians.

Little is known about Letopolis other than that it had been an important religious centre dedicated to the god Horus the Elder as early as the First or Second Dynasties, perhaps even harking back to the late prehistoric period. Today nothing remains of Letopolis except for a few dilapidated ruins dating from the late period attributed to the last indigenous pharaohs, including Nectanebo I (380-362 BC). Ausim is now a typical slum of Greater Cairo (sadly the same fate has befallen ancient Heliopolis, the modern Matareya).

15

At any rate, it is very tempting to postulate that there might once have existed here at Letopolis an observation tower from which the ancient surveyors could have projected their grid lines towards Heliopolis in the east and the various pyramid fields in the south. George Goyon, the director of the Centre National de Recherches Scientifiques in Paris and professor at the Collège de France, certainly thinks so . . .

15

At any rate, it is very tempting to postulate that there might once have existed here at Letopolis an observation tower from which the ancient surveyors could have projected their grid lines towards Heliopolis in the east and the various pyramid fields in the south. George Goyon, the director of the Centre National de Recherches Scientifiques in Paris and professor at the Collège de France, certainly thinks so . . .

In the early 1970s George Goyon took a keen interest in the writings of the Roman geographer Strabo, who had visited Egypt in

c

. AD 30. According to Strabo:

c

. AD 30. According to Strabo:

. . . the city of Kerkasore, which is located near the observatory of Eudoxus, is in the Libyan side (i.e. western bank) of the Nile, where there is a sort of watch-tower which can be seen from Heliopolis [and] from which Eudoxus made his observations of the movement of the celestial bodies. There is the Letopolite Nome.

16

Goyon had not heard before of this mysterious city of Kerkasore, but because of the description and location details that Strabo gave, Goyon suspected that he was in fact talking about the ancient site of Letopolis, and that the watch tower he was referring to was some kind of observation tower used by the ancient astronomer-priests of Heliopolis. Since Strabo had called this tower the ‘observatory of Eudoxus’, Goyon decided to investigate whether it was indeed at Letopolis that Eudoxus might have made his famous observations of ‘the movement of the celestial bodies’.

Isometric view of the Giza Plateau, Letopolis and Heliopolis

Eudoxus of Cnidus (408-355 BC) was one of Greece’s most eminent mathematicians, and it is recorded that he visited Egypt in

c

. 370 BC for two years as a student at the sun temple of Heliopolis, there to learn the science of astronomy from the Egyptian priests. From an analysis of Strabo’s commentary and also those of other ancient writers who mentioned the mysterious location of Kerkasore in passing (Herodotus, Pomponius Mela, and Quintus Curtius), Goyon was able to establish that it had been located about 100 stadium (15.7 kilometres) due north of Giza and 100 stadium due west of Heliopolis. These coordinates mark a spot very near the present modern town of Ausim. Seeing that Ausim was due north of the Great Pyramid, Goyon became convinced that the tower from which Eudoxus had studied the stars might have been the remnants of a very ancient bollard that had served as a sighting point for the ancient pyramid-builders to maintain the monument in a true north orientation during its construction.

17

He suggested that the Eudoxus tower had been, in probability, very similar to the squat obelisk-shaped towers that stood at the sun temples at Abu Ghorab, and that, like them, its top was probably fitted with a polished metal disc from which reflected the sun’s rays like that of a lighthouse.

18

c

. 370 BC for two years as a student at the sun temple of Heliopolis, there to learn the science of astronomy from the Egyptian priests. From an analysis of Strabo’s commentary and also those of other ancient writers who mentioned the mysterious location of Kerkasore in passing (Herodotus, Pomponius Mela, and Quintus Curtius), Goyon was able to establish that it had been located about 100 stadium (15.7 kilometres) due north of Giza and 100 stadium due west of Heliopolis. These coordinates mark a spot very near the present modern town of Ausim. Seeing that Ausim was due north of the Great Pyramid, Goyon became convinced that the tower from which Eudoxus had studied the stars might have been the remnants of a very ancient bollard that had served as a sighting point for the ancient pyramid-builders to maintain the monument in a true north orientation during its construction.

17

He suggested that the Eudoxus tower had been, in probability, very similar to the squat obelisk-shaped towers that stood at the sun temples at Abu Ghorab, and that, like them, its top was probably fitted with a polished metal disc from which reflected the sun’s rays like that of a lighthouse.

18

What made Goyon’s hypothesis so convincing was that it was well-known that Letopolis, since earliest times, had been the capital of the second Nome of Lower Egypt, whose emblem was a bull’s thigh, which, according to Goyon, ‘means the constellation of Ursa Major’ (or rather the Plough, as we have seen earlier).

19

British Egyptologist G.A. Wainwright had also shown that the deity known as ‘Horus of Letopolis’ was the traditional keeper of the ritualistic adze used in the ‘opening of the mouth’ that was shaped like the Plough and bore the same name, i.e.

meskhetiu

, or bull’s thigh.

20

We should recall that this constellation was, of course, the celestial target for the ‘stretching of the cord’ ceremony to align pyramids and temples towards the north. But there was, too, another important constellation involved in this alignment ceremony and which, according to Richard Wilkinson, relied on sightings not only of the Great Bear but also of ‘the Orion constellations’.

21

Evidence of such astronomical symbolism to denote the north and south of a place is found at the temple of Horus at Edfu, where an inscription referring to the ‘stretching of the cord’ ceremony also states that the north side of the temple was the ‘bull’s thigh’ and the south side was ‘Orion’.

22

The same north-south symbolism is also found in many of the so-called astronomical ceilings of the New Kingdom where north is symbolised by the bull’s thigh and south by Orion (and also Sirius).

19

British Egyptologist G.A. Wainwright had also shown that the deity known as ‘Horus of Letopolis’ was the traditional keeper of the ritualistic adze used in the ‘opening of the mouth’ that was shaped like the Plough and bore the same name, i.e.

meskhetiu

, or bull’s thigh.

20

We should recall that this constellation was, of course, the celestial target for the ‘stretching of the cord’ ceremony to align pyramids and temples towards the north. But there was, too, another important constellation involved in this alignment ceremony and which, according to Richard Wilkinson, relied on sightings not only of the Great Bear but also of ‘the Orion constellations’.

21

Evidence of such astronomical symbolism to denote the north and south of a place is found at the temple of Horus at Edfu, where an inscription referring to the ‘stretching of the cord’ ceremony also states that the north side of the temple was the ‘bull’s thigh’ and the south side was ‘Orion’.

22

The same north-south symbolism is also found in many of the so-called astronomical ceilings of the New Kingdom where north is symbolised by the bull’s thigh and south by Orion (and also Sirius).

Bearing this in mind, it follows that an ancient observer placed at the Giza plateau at night looking due north would have seen the Plough transiting directly over Letopolis, while another observer placed at Letopolis looking due south would have seen Orion’s belt transiting over the Great Pyramid. Giza and Letopolis are thus interrelated, and the latter, which is also due west of Heliopolis, must by necessity be added to the master plan that I am proposing. These three locations - Giza, Letopolis and Heliopolis - form a huge Pythagorean triangle, with two of its corners - the north at Letopolis and the south at Giza - appearing to represent two prominent constellations, the Plough and Orion’s belt, on the ground. These two constellations are on the west bank of the Milky Way. Could the third corner of the triangle, at Heliopolis, which lies across the Nile some 18 kilometres due east of Letopolis, also be denoting a prominent constellation that is on the eastern bank of the Milky Way and is seen due east from Letopolis? Which constellation could that be? A fortuitous inscription that refers to the ‘stretching of the cord’ ceremony gives us a clue: ‘The king has built the Great Temple of Ra-Horakhti in conformity with the horizon which bears his disc; the cord was stretched by his Majesty himself, having held the rod in his hand with Seshat . . .’

23

23

Could the Great Temple of Ra-Horakhti-a name applied specifically to the Great Temple of Heliopolis - have represented a prominent constellation that coalesced with the sun disc in the eastern horizon at dawn?

‘An important mythological aspect of the solar god in the heavens,’ wrote Egyptologist Richard Wilkinson, ‘is found in his identity as a cosmic lion.’ Furthermore, Wilkinson was of the opinion that ‘the stellar constellation now known as Leo was also recognised by the Egyptians as being in the form of a recumbent lion . . . (and that) the constellation was directly associated with the sun god’.

24

Wilkinson proposed that when the sun god Ra rose to prominence during the Fourth Dynasty, he was ‘coalesced

’

with the primitive god Horakhti thus ‘becoming Ra-Horakhti as the morning sun’.

25

24

Wilkinson proposed that when the sun god Ra rose to prominence during the Fourth Dynasty, he was ‘coalesced

’

with the primitive god Horakhti thus ‘becoming Ra-Horakhti as the morning sun’.

25

Most Egyptologists will agree with Wilkinson on his last statement, namely that Horakhti (Horus-of-the-Horizon) was coalesced with the sun-god Ra to become Ra-Horakhti, together a symbol of the rising sun in the east. This is, in any case, confirmed by the Pyramid Texts, which refer to the rising of Ra-Horakhti in the ‘eastern side of the sky . . . the place where the gods are born (i.e rise)’.

26

Egyptologists will also readily agree that an important mythological aspect of the sun-god, especially at sunrise and sunset, was that of the cosmic lion. Indeed, as Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson pointed out:

26

Egyptologists will also readily agree that an important mythological aspect of the sun-god, especially at sunrise and sunset, was that of the cosmic lion. Indeed, as Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson pointed out:

Since lions (in Egypt) characteristically lived on the desert margins, they came to be considered as the guardians of the eastern and western horizons, the places of sunrise and sunset. In this connection, they sometimes replaced the eastern and western mountains, symbolic of past and future, on either sign of the ‘horizon’ hieroglyph (

Akhet

) . . . Since the sun itself could be represented as a lion, Chapter 62 of the Book of the Dead states: ‘May I be granted power over the waters . . . for I am he who crosses the sky, I am the lion of Ra’ . . .

27

Few, however, have found any significance in the fact that the word

akhet

means both ‘the horizon’ and ‘the flood season’. It was at this special time of year that the constellation of Leo was seen rising at dawn in the eastern horizon, or, as astrologers would say, the sun was coalesced in Leo. In spite of such tantalising clues, however, hardly any Egyptologists agree with Wilkinson that the solar lion of the ancient Egyptians can be equated to our constellation of Leo. But I do. I side with Wilkinson on this issue because I am convinced that the solar lion mentioned in many ancient Egyptian texts and depicted on their astronomical drawings was, in fact, the constellation Leo. I am also convinced that this can be proved.

akhet

means both ‘the horizon’ and ‘the flood season’. It was at this special time of year that the constellation of Leo was seen rising at dawn in the eastern horizon, or, as astrologers would say, the sun was coalesced in Leo. In spite of such tantalising clues, however, hardly any Egyptologists agree with Wilkinson that the solar lion of the ancient Egyptians can be equated to our constellation of Leo. But I do. I side with Wilkinson on this issue because I am convinced that the solar lion mentioned in many ancient Egyptian texts and depicted on their astronomical drawings was, in fact, the constellation Leo. I am also convinced that this can be proved.

The very existence of Egypt, its agriculture, its ecology and the survival of its people, depended on the flood. If ever the flood waters failed to come, total disaster would ensue. Indeed, it would not be any exaggeration to say that the flood was the very lifeblood of Egypt, and that nothing terrorised the ancient Egyptians more than the thought that it would one day fail to arrive, or that its waters would fail to rise to the optimum level measured at Elephantine near Aswan. As Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson explain:

Egypt’s agricultural prosperity depended on the annual inundation of the Nile. For crops to flourish it was desirable that the Nile should rise about eight metres above a zero point at the first cataract near Aswan. A rise of only seven metres would produce a lean year, while six metres would lead to famine. That such famines actually occurred in ancient Egypt is well documented from a number of sources, both literary and artistic.

28

On the small rocky island of Sehel south of Elephantine is the so-called ‘famine stela’, on which is inscribed the story of a terrible seven-year famine that decimated the population and livestock of Egypt during the reign of Djoser. Another protracted famine must have occurred some time during the Fifth Dynasty, for depictions of starving people were found on the walls of the causeway of the pyramid of Unas at Saqqara.

29

These terrible famines were surely caused by too weak a flood. But it was no great boon to have too strong a flood either, for this also spelt a tragedy on a different scale with the torrential waters drowning crops and destroying villages along their ruthless path. The flood, quite simply, had to be just right. Not too weak and not too strong. Yet it was not only that the water level had to rise eight metres at Elephantine, but also, and perhaps more so, that the celestial signs had to be manifest at the right time of year. This right time of year was, of course, the summer solstice, when the sun reached its apogee. Only when these two essential requirements were fulfilled would there be a perfect flood.

29

These terrible famines were surely caused by too weak a flood. But it was no great boon to have too strong a flood either, for this also spelt a tragedy on a different scale with the torrential waters drowning crops and destroying villages along their ruthless path. The flood, quite simply, had to be just right. Not too weak and not too strong. Yet it was not only that the water level had to rise eight metres at Elephantine, but also, and perhaps more so, that the celestial signs had to be manifest at the right time of year. This right time of year was, of course, the summer solstice, when the sun reached its apogee. Only when these two essential requirements were fulfilled would there be a perfect flood.

Other books

Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television by Mander, Jerry

The Summer of Our Discontent by Robin Alexander

Spiralling Skywards: Falling (Contradictions #1) by Jones,Lesley

A Thread So Thin by Marie Bostwick

Queen of the Pirates by Blaze Ward

Ignite (Midnight Fire Series Book One) by Kaitlyn Davis

Brie’s Denver Desires (Submissive in Love, #2) by Red Phoenix

The Bullwhip Breed by J. T. Edson

Gianni - The Santinis by Melissa Schroeder

Where the Broken Lie by Rempfer, Derek