The Egypt Code (6 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

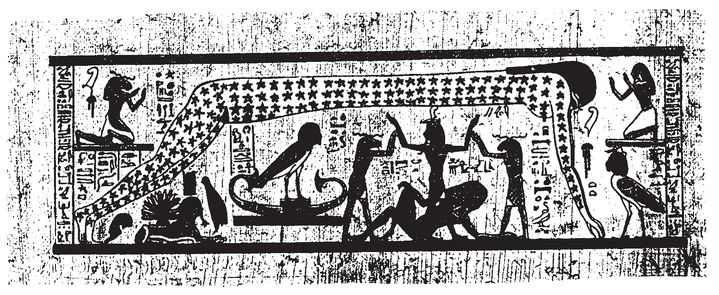

The goddess Nut (the sky)

There exist ancient Egyptian teachings dating from the first century known as the

Corpus Hermeticum

, which, as we have briefly mentioned earlier, express the fundamentals of this belief system which saw a connection or ‘influence’ between the cycle of the stars and that of men and all things on earth:

Corpus Hermeticum

, which, as we have briefly mentioned earlier, express the fundamentals of this belief system which saw a connection or ‘influence’ between the cycle of the stars and that of men and all things on earth:

God arranged the Zodiac [the twelve seasonal constellations] in accord with the cycles of nature . . . (and) . . . devised a secret engine (‘viz. the system of the stars’) linked to unerring and inevitable fate, to which all things in men’s lives, from their birth to their final destruction shall of necessity be brought into subjection; and all other things on earth likewise shall be controlled by the working of this engine . . .

29

Mulling over this archaic perception of the visible world, I knew that I was trying to somehow get into the mindset of the ancient Egyptians. I had to stop thinking as scientific man and begin thinking like cosmic man. I had to bring myself to believe, like they did, that the constellations were the wheel of a cosmic engine that could influence events on earth. I had to believe, like they did, that the king and his

ka

could control the working of this cosmic engine. Finally I had to believe, like they did, that the Step Pyramid complex was not a cemetery as such but a ‘centre of regulation’ from which the king could control the cosmos. It was, I knew, the only way to truly understand the ancient Egyptians and their legacy of pyramids and temples.

ka

could control the working of this cosmic engine. Finally I had to believe, like they did, that the Step Pyramid complex was not a cemetery as such but a ‘centre of regulation’ from which the king could control the cosmos. It was, I knew, the only way to truly understand the ancient Egyptians and their legacy of pyramids and temples.

Another inscription from Rawer’s

serdab

provided a further missing piece from this strange and elaborate puzzle. According to Blackman there was, just above the squint on the north face of the

serdab

, a line of hieroglyphs that simply stated: ‘the eyes of the

ka

house’.

30

But the term ‘

ka-

house’, according to Egyptologists, referred not to the

serdab

alone but to the whole

mastaba

complex to which it was attached. This, of course, implied that the two peepholes on the north face of Djoser’s

serdab

were also regarded as the ‘eyes’ of the whole Step Pyramid complex. From my previous studies I was aware that pyramids were not only thought of as stars on earth but also as

being

the pharaoh himself. In the Pyramid Texts there are numerous claims that the soul, or

ba

, of a dead king became a ‘star’.

31

Also, as Richard Wilkinson further pointed out, ‘Nut (the sky-goddess) also became inextricably associated with the concept of resurrection in Egyptian funerary beliefs, and the dead were believed to become stars in the body of the goddess.’

32

serdab

provided a further missing piece from this strange and elaborate puzzle. According to Blackman there was, just above the squint on the north face of the

serdab

, a line of hieroglyphs that simply stated: ‘the eyes of the

ka

house’.

30

But the term ‘

ka-

house’, according to Egyptologists, referred not to the

serdab

alone but to the whole

mastaba

complex to which it was attached. This, of course, implied that the two peepholes on the north face of Djoser’s

serdab

were also regarded as the ‘eyes’ of the whole Step Pyramid complex. From my previous studies I was aware that pyramids were not only thought of as stars on earth but also as

being

the pharaoh himself. In the Pyramid Texts there are numerous claims that the soul, or

ba

, of a dead king became a ‘star’.

31

Also, as Richard Wilkinson further pointed out, ‘Nut (the sky-goddess) also became inextricably associated with the concept of resurrection in Egyptian funerary beliefs, and the dead were believed to become stars in the body of the goddess.’

32

This intriguing stellar connection of the king and his pyramid is made even more evident by a series of inscriptions and engravings found on the capstone (pyramidion) of a royal pyramid from Dashour that belonged to a Twelfth Dynasty pharaoh, Amenemhet III. On the east side of the pyramidion are engraved two large ‘eyes’ and a line of hieroglyphs that read: ‘May the face of the king be opened so that he may see the Lord of the Horizon when he crosses the sky; may he cause the king to shine as a god, lord of eternity and indestructible.’

33

The name of the pyramid that bore this capstone was ‘Amenemhet is beautiful’, which, not surprisingly, meant to Egyptologist Mark Lehner that ‘Like the names of the pyramids . . . the eyes (on the pyramidion) tells us that the pyramids were personifications of the dead kings who were buried within them.’

34

The American Egyptologist Alexander Piankoff, well known for his translation of the Pyramid Texts of Unas (a Fifth Dynasty king who built a pyramid at Saqqara), also wrote that ‘the embalmed body of the king lay in or under the pyramid, which together with its entire compound, was considered his body. The pyramids were personified . . .’ In addition Piankoff also showed the personification of the king’s pyramid with the title that queens of the Sixth Dynasty adopted. As an example he gives the title of King Unas’s daughter as being ‘the royal daughter of the body of “Perfect are the places of Unas”’, the latter epithet being the name of Unas’s pyramid. According to Piankoff, the dead king rested in or under his pyramid ‘as Osiris in the Netherworld, and received his sustenance through an elaborate ritual’.

35

33

The name of the pyramid that bore this capstone was ‘Amenemhet is beautiful’, which, not surprisingly, meant to Egyptologist Mark Lehner that ‘Like the names of the pyramids . . . the eyes (on the pyramidion) tells us that the pyramids were personifications of the dead kings who were buried within them.’

34

The American Egyptologist Alexander Piankoff, well known for his translation of the Pyramid Texts of Unas (a Fifth Dynasty king who built a pyramid at Saqqara), also wrote that ‘the embalmed body of the king lay in or under the pyramid, which together with its entire compound, was considered his body. The pyramids were personified . . .’ In addition Piankoff also showed the personification of the king’s pyramid with the title that queens of the Sixth Dynasty adopted. As an example he gives the title of King Unas’s daughter as being ‘the royal daughter of the body of “Perfect are the places of Unas”’, the latter epithet being the name of Unas’s pyramid. According to Piankoff, the dead king rested in or under his pyramid ‘as Osiris in the Netherworld, and received his sustenance through an elaborate ritual’.

35

There are several pyramids, as we have already seen, that bore unequivocal stellar names, such as ‘Djedefre is a

sehedu

star’, ‘Horus is the Star at the Head of the Sky’ and ‘Nebka is a Star’. We have also seen how Alexander Badawy argued that other pyramids which were identified with the king’s

ba

, or soul, must be taken as stellar since the

ba

becomes a star in the firmament. By simple transposition, if A equals B, and B equals C, then A must equal C. In other words, if the king becomes a star in the sky and he also becomes his pyramid in the Memphite necropolis, it must follow that his star is also to be regarded as his pyramid and vice versa. This would certainly indicate that certain clusters of pyramids such as those of Giza and Abusir may represent clusters of stars, i.e. constellations. Let us leave this intriguing possibility for a moment, however, and return to the two peepholes of Djoser’s

serdab

.

sehedu

star’, ‘Horus is the Star at the Head of the Sky’ and ‘Nebka is a Star’. We have also seen how Alexander Badawy argued that other pyramids which were identified with the king’s

ba

, or soul, must be taken as stellar since the

ba

becomes a star in the firmament. By simple transposition, if A equals B, and B equals C, then A must equal C. In other words, if the king becomes a star in the sky and he also becomes his pyramid in the Memphite necropolis, it must follow that his star is also to be regarded as his pyramid and vice versa. This would certainly indicate that certain clusters of pyramids such as those of Giza and Abusir may represent clusters of stars, i.e. constellations. Let us leave this intriguing possibility for a moment, however, and return to the two peepholes of Djoser’s

serdab

.

Looking deeper into this issue of Djoser’s

serdab

, I was pleased to find that there were many eminent scholars who had also independently arrived at more or less the same conclusion as I had regarding the stellar function of the two peepholes. For example, the French Egyptologist Christiane Ziegler concluded that ‘through the two peep-holes the king would gaze towards the “imperishable” stars near the North Pole’.

36

Although Ziegler did not venture why this was a necessary feature of the complex, she nonetheless recognised that the peepholes had a stellar function. She was echoed by Mark Lehner, who wrote that

serdab

, I was pleased to find that there were many eminent scholars who had also independently arrived at more or less the same conclusion as I had regarding the stellar function of the two peepholes. For example, the French Egyptologist Christiane Ziegler concluded that ‘through the two peep-holes the king would gaze towards the “imperishable” stars near the North Pole’.

36

Although Ziegler did not venture why this was a necessary feature of the complex, she nonetheless recognised that the peepholes had a stellar function. She was echoed by Mark Lehner, who wrote that

On the northern side of his Saqqara Step Pyramid Djoser emerges from his tomb in statue form, into a statue-box, or

Serdab

, which has just such a pair of peepholes to allow him to see out

37

. . . with eyes once inlaid with rock crystal, Djoser’s statue gazes out through peepholes in the serdab box, tilted upwards 13° to the northern sky where the king joined the circumpolar stars . . .

38

To support such a conclusion, Lehner quoted a passage from the

Book of the Dead

in which the dead person is made to say: ‘Open for me are the double doors of the sky, open for me are the double doors of the earth. Open for me are the bolts of Geb, exposed for me are the roof . . . and the Twin Peepholes.’ In addition to Ziegler’s and Lehner’s conclusions renowned Russian astronomer Professor Alexander Gurshtein wrote that ‘On the north side of Imhotep’s Step Pyramid there is a small stone cubicle canted towards the north, with a pair of tiny holes in its façade likely for astronomical observations by the dead pharaoh.’

39

Book of the Dead

in which the dead person is made to say: ‘Open for me are the double doors of the sky, open for me are the double doors of the earth. Open for me are the bolts of Geb, exposed for me are the roof . . . and the Twin Peepholes.’ In addition to Ziegler’s and Lehner’s conclusions renowned Russian astronomer Professor Alexander Gurshtein wrote that ‘On the north side of Imhotep’s Step Pyramid there is a small stone cubicle canted towards the north, with a pair of tiny holes in its façade likely for astronomical observations by the dead pharaoh.’

39

In my experience with such things, it is an excellent sign when several researchers come to the same conclusion on the same issue, because the likelihood is that they are on the right track. Indeed, it had to be admitted that the evidence for a stellar function for the

serdab

was overwhelming, textually, astronomically and architecturally. It now remained to work out which specific star in the northern sky was targeted by the peepholes.

serdab

was overwhelming, textually, astronomically and architecturally. It now remained to work out which specific star in the northern sky was targeted by the peepholes.

And why.

To see Djoser’s

serdab

one has to walk past the east side of the Step Pyramid and then turn left at the far corner. From here one can already get a side view of the

serdab

and even a glimpse at the

ka

statue through a small glassed window on the upper part of its side. Once you stand in front of the

serdab

, you will immediately see the peepholes.

serdab

one has to walk past the east side of the Step Pyramid and then turn left at the far corner. From here one can already get a side view of the

serdab

and even a glimpse at the

ka

statue through a small glassed window on the upper part of its side. Once you stand in front of the

serdab

, you will immediately see the peepholes.

By leaning back against the north wall and fixing your eyes at the place in the sky where the peepholes are directed, you can mentally project an ‘X’ to mark the spot. And even though it will be broad daylight, it is not too hard to imagine how the Plough constellation would sweep over the X during its diurnal cycle. Now if the angle of inclination of the

serdab

and its azimuth could be known with a good degree of accuracy, it would be a relatively easy excercise to calculate which one of the Plough’s seven bright stars would superimpose on the X at the time the

serdab

was built,

c

. 2650 BC. Normally such data should be relatively easy to obtain in Egyptological manuals or publications. As it turned out, however, it proved to be a far more complicated matter than I had anticipated.

serdab

and its azimuth could be known with a good degree of accuracy, it would be a relatively easy excercise to calculate which one of the Plough’s seven bright stars would superimpose on the X at the time the

serdab

was built,

c

. 2650 BC. Normally such data should be relatively easy to obtain in Egyptological manuals or publications. As it turned out, however, it proved to be a far more complicated matter than I had anticipated.

Finding the azimuth or orientation of the

serdab

’s north face was the least troublesome task. All I needed was the azimuth of the north face of the Step Pyramid to which the

serdab

was attached. I was aware that the latest study undertaken on the astronomical orientation of Egyptian pyramids was by the German Egyptologist Josef Dorner in the early 1980s. Unfortunately Dorner did not publish his data but simply lodged it in thesis format at the University of Innsbruck. Fortuitously, the Italian astronomer Giulio Magli, of the Politecnico di Milano, whom I know very well, had managed to obtain a copy of Dorner’s thesis and was happy to pass me the data on the Step Pyramid that I needed. I found out that, according to Dorner, the sides of the Step Pyramid ‘

do not exactly face the cardinal points, the northern front being 4°35

′

east of true north

’.

40

Dorner - and other Egyptologists - tend to attribute this rather large deviation from true north to either carelessness or inefficiency on the part of the ancient surveyors. On closer scrutiny, however, this explanation does not hold water. It was well known, for example, that the Egyptians of the Pyramid Age were more than capable of orienting pyramids to much higher levels of accuracy than this. The Giza pyramids are, of course, a prime example of this, with alignments within the 20 arc minute level of accuracy. The Great Pyramid, in point of fact, is accurate within an astounding 3 arc minutes from true north (0.05°), which is almost 100 times more accurate than the 275 arc minutes (4° 35′) for the Step Pyramid! Yet there is no good reason to suppose that the surveyors of the Step Pyramid were either less efficient or did not have the same sighting devices and methodologies that their immediate successors had. Indeed,

mastabas

that were built

before

the Step Pyramid were aligned well within the 1° level of accuracy. Furthermore, any practising surveyor will confirm that an error might be considered if the deviation was no more than 1°, but a deviation of 4° 35′ is far too large to be assumed a mere mistake. Even the most inexperienced surveyor using the most rudimentary of sighting instruments would not make such a slip-up, unless he deliberately wanted to. There are only two realistic explanations for this large deviation: either the surveyors were not interested in true north, or, more likely in my view,

they were aiming at something else in the sky that was at 4° 35

′

east from true north

. My gut feeling was that the second explanation was probably the right one. Experience had shown time and time again that nothing the pyramid builders did was left to chance.

serdab

’s north face was the least troublesome task. All I needed was the azimuth of the north face of the Step Pyramid to which the

serdab

was attached. I was aware that the latest study undertaken on the astronomical orientation of Egyptian pyramids was by the German Egyptologist Josef Dorner in the early 1980s. Unfortunately Dorner did not publish his data but simply lodged it in thesis format at the University of Innsbruck. Fortuitously, the Italian astronomer Giulio Magli, of the Politecnico di Milano, whom I know very well, had managed to obtain a copy of Dorner’s thesis and was happy to pass me the data on the Step Pyramid that I needed. I found out that, according to Dorner, the sides of the Step Pyramid ‘

do not exactly face the cardinal points, the northern front being 4°35

′

east of true north

’.

40

Dorner - and other Egyptologists - tend to attribute this rather large deviation from true north to either carelessness or inefficiency on the part of the ancient surveyors. On closer scrutiny, however, this explanation does not hold water. It was well known, for example, that the Egyptians of the Pyramid Age were more than capable of orienting pyramids to much higher levels of accuracy than this. The Giza pyramids are, of course, a prime example of this, with alignments within the 20 arc minute level of accuracy. The Great Pyramid, in point of fact, is accurate within an astounding 3 arc minutes from true north (0.05°), which is almost 100 times more accurate than the 275 arc minutes (4° 35′) for the Step Pyramid! Yet there is no good reason to suppose that the surveyors of the Step Pyramid were either less efficient or did not have the same sighting devices and methodologies that their immediate successors had. Indeed,

mastabas

that were built

before

the Step Pyramid were aligned well within the 1° level of accuracy. Furthermore, any practising surveyor will confirm that an error might be considered if the deviation was no more than 1°, but a deviation of 4° 35′ is far too large to be assumed a mere mistake. Even the most inexperienced surveyor using the most rudimentary of sighting instruments would not make such a slip-up, unless he deliberately wanted to. There are only two realistic explanations for this large deviation: either the surveyors were not interested in true north, or, more likely in my view,

they were aiming at something else in the sky that was at 4° 35

′

east from true north

. My gut feeling was that the second explanation was probably the right one. Experience had shown time and time again that nothing the pyramid builders did was left to chance.

It was at this point that I could have kicked myself for not remembering earlier a very important and very ancient ceremony related to the astronomical orientation of pyramids and temples. With mounting excitement I realised that the missing piece of this puzzle might well be in the hands of a very unusual and very well-groomed lady surveyor.

Since the beginning of their recorded history the ancient Egyptians had performed a religious ceremony known as ‘the stretching of the cord’ to align the axis of their sacred monuments. This ceremony involved the king and a rather fetching priestess who personified the goddess Seshat. Seshat was the erudite one among the many goddesses of ancient Egypt. Some even think of her as the archetype of female librarians and civil engineers. Tall, slender and very becoming, she was adored and venerated by the royal scribes in the ‘House of Life’ (temple library), for she was among other things the patroness of sacred writing, and also the keeper of the royal annals relating to the coronations and jubilees of kings.

41

She also had another, more technical role, which involved assisting the king in fixing the four corners of his future temples and pyramids and aligning them towards the stars. Oddly, however, you won’t find much written about the goddess Seshat in Egyptological textbooks. For example, Mark Lehner pays no attention to her in his recent book

The Complete Pyramids

, and Richard H. Wilkinson hardly mentions her in his latest book

The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt

.

42

Other Egyptologists either choose to ignore Seshat like Lehner did,

43

or mention her in the most scant of ways, as if she is but a footnote in Egyptian mythology. And even on those rare occasions when she is discussed at greater length, she is generally presented as a pretty bimbo who accompanies the king in the ‘stretching of the cord’ ritual only to give decorum and piquancy to the act. This, of course, is unfortunate; for if the truth be told about Seshat, as one Egyptologist did in the 1940s, this elusive goddess comes across not just as a pretty face in the Egyptian pantheon, by as a high-powered woman who decided on the length of the king’s reign and, according to at least one eminent Egyptologist, probably his life.

44

41

She also had another, more technical role, which involved assisting the king in fixing the four corners of his future temples and pyramids and aligning them towards the stars. Oddly, however, you won’t find much written about the goddess Seshat in Egyptological textbooks. For example, Mark Lehner pays no attention to her in his recent book

The Complete Pyramids

, and Richard H. Wilkinson hardly mentions her in his latest book

The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt

.

42

Other Egyptologists either choose to ignore Seshat like Lehner did,

43

or mention her in the most scant of ways, as if she is but a footnote in Egyptian mythology. And even on those rare occasions when she is discussed at greater length, she is generally presented as a pretty bimbo who accompanies the king in the ‘stretching of the cord’ ritual only to give decorum and piquancy to the act. This, of course, is unfortunate; for if the truth be told about Seshat, as one Egyptologist did in the 1940s, this elusive goddess comes across not just as a pretty face in the Egyptian pantheon, by as a high-powered woman who decided on the length of the king’s reign and, according to at least one eminent Egyptologist, probably his life.

44

Other books

Last Orders: The War That Came Early by Harry Turtledove

An Innocent Abroad: A Jazz Age Romance by Romy Sommer

How I Live Now by Meg Rosoff

Teacher: The Final Act (A Hollywood Rock n' Romance Trilogy #3) by R. L. Merrill

The Pursuit of Other Interests: A Novel by Jim Kokoris

Being Jolene by Caitlin Kerry

Dangerous Grounds by Shelli Stevens

Chasing Justice by Danielle Stewart

The Quickening by Michelle Hoover