The Egypt Code (27 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

Author at the Temple of Karnak, west entrance.

Sir Norman Lockyer

c

. 1899.

c

. 1899.

Elephantine Island at Aswan in the background. Author and view from the gardens of the Old Cataract Hotel.

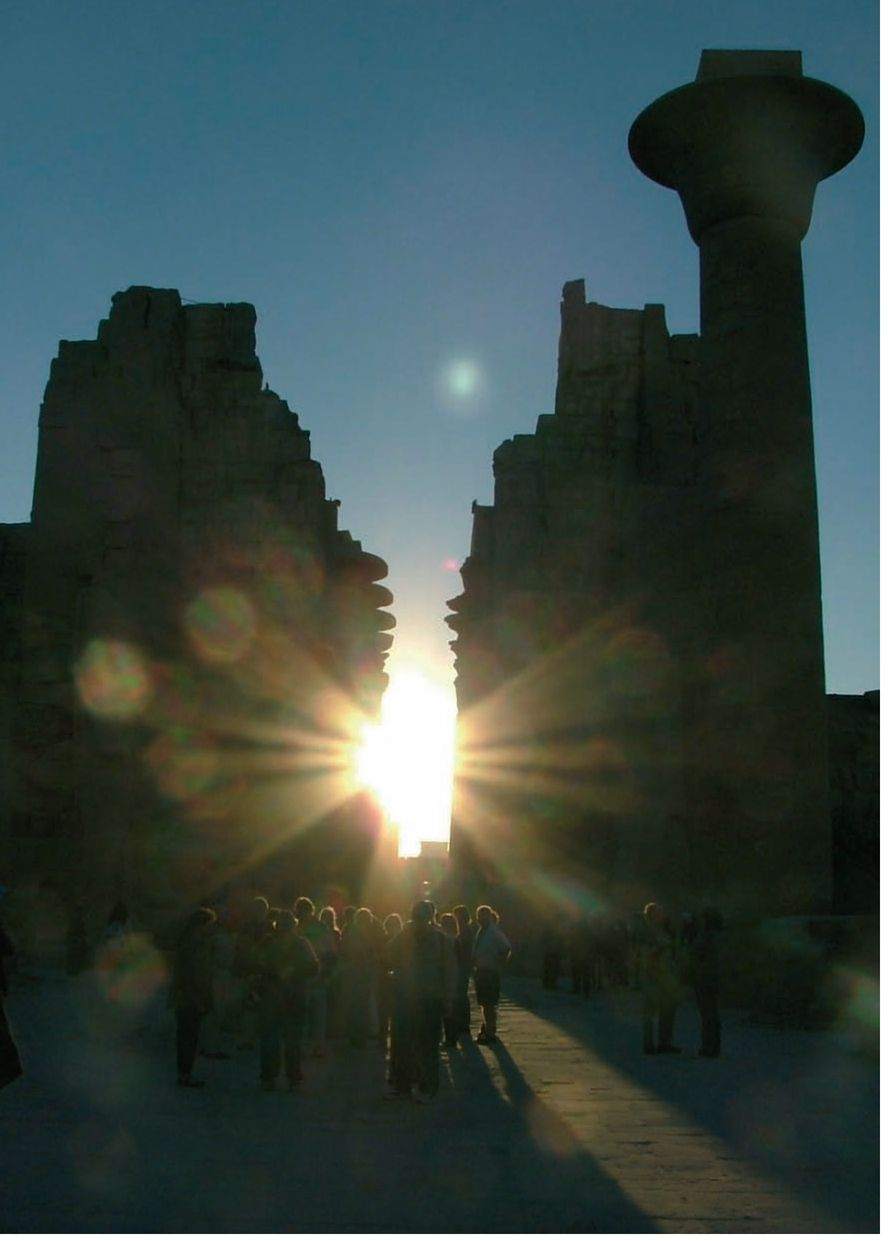

Sunrise at winter solstice, Temple of Karnak.

This surely raises a question: could the idea of an Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt be rooted in astronomy?

In 1891 the English astronomer Sir Norman Lockyer developed a deep fascination for ancient Egypt and its mysterious pyramids and temples. He was puzzled as to why a people who so deeply venerated the sun, and who especially observed its rising in the eastern horizon fluctuating throughout the yearly cycle from a point in the north at summer solstice to one in the south at winter solstice, should also have their country similarly disposed with a distinct north and a distinct south concept. After giving much reflection to this geographical peculiarity, as well as to the ancient Egyptians’ intense religious focus on the sky, Lockyer began to suspect that ‘the double origin of the people thus suggested on astronomical grounds may be the reason for the name of the “double country” used specially in the title of kings’.

12

Almost a century later, in 1992, the very same idea came to the astronomer Ronald Wells, who was more specific than Lockyer when he wrote that

12

Almost a century later, in 1992, the very same idea came to the astronomer Ronald Wells, who was more specific than Lockyer when he wrote that

Monitoring the movements of the sun god must have been one of the earliest of predynastic observations in the Nile Valley; and it would have been natural to interpret the sun’s yearly motion along the eastern horizon from the southernmost point at the winter solstice to the northernmost point at the summer solstice and back as journeys or visitations of the god to each of the two kingdoms - the due east point forming at least the heavenly boundary between them.

13

We have seen how the Egyptians started their calendar in 2781 BC with the summer solstice when the latter coincided with the heliacal rising of Sirius and also with the opening of the flood season (Akhet). Not surprisingly, therefore, this first day of the year, or ‘New Year’s Day’, was referred to as

wp rnpt

, literally ‘The Opener of the Year’, and was used as an epithet for Sirius.

14

In the civil calendar it was tabulated as I Akhet 1, i.e. first month, season of Akhet, first day. Eventually it was simply called 1 Thoth, which was the first day of the first month of the year, in the same way we call New Year’s Day 1 January in our current Gregorian calendar.

15

But another, perhaps even more meaningful, name for the New Year’s Day was

ms-wtr

, literally ‘The Birth of Ra’ or, to be more precise, ‘The Birth of Ra-Horakhti’ (Ra-Horus-of-the-Horizon). In 1905 the chronologist Eduard Meyer demonstrated that ‘The Birth of Ra’ had denoted the summer solstice. But this only holds true for the date

c

. 2781 BC when the New Year’s Day coincided with the summer solstice. Because the civil calendar was a drifted calendar which displaced the summer solstice by a quarter of a day each year, the same thing happened to the New Year’s Day and, by extension, to ‘The Birth of Ra’. Simple calculation shows that after 753 years (1506 ÷ 2 = 753 years, half the Great Solar Cycle), the ‘Birth of Ra’ had drifted to the

winter

solstice and thus a massive 54° to the south of the summer solstice sunrise point. In other words, in the year 2028 BC (2781-753 = 2028) the sun disc rose 28°

south

-of-east at the winter solstice and not, as it had done originally in 2781 BC, 28°

north

-of-east at the summer solstice. Surely this conjunction of ‘The Birth of Ra’ with the winter solstice, marked by the extreme southerly position of the sun disc on the horizon, must have had immense religious significance to the priests of the solar cult who were based in the southern extreme of Egypt. It must have seemed as if the cosmic order had ordained that now it was their turn to be controllers of the sun religion and that the reigning pharaoh should now also move the capital of the country from its location in the north to a new location in the south.

wp rnpt

, literally ‘The Opener of the Year’, and was used as an epithet for Sirius.

14

In the civil calendar it was tabulated as I Akhet 1, i.e. first month, season of Akhet, first day. Eventually it was simply called 1 Thoth, which was the first day of the first month of the year, in the same way we call New Year’s Day 1 January in our current Gregorian calendar.

15

But another, perhaps even more meaningful, name for the New Year’s Day was

ms-wtr

, literally ‘The Birth of Ra’ or, to be more precise, ‘The Birth of Ra-Horakhti’ (Ra-Horus-of-the-Horizon). In 1905 the chronologist Eduard Meyer demonstrated that ‘The Birth of Ra’ had denoted the summer solstice. But this only holds true for the date

c

. 2781 BC when the New Year’s Day coincided with the summer solstice. Because the civil calendar was a drifted calendar which displaced the summer solstice by a quarter of a day each year, the same thing happened to the New Year’s Day and, by extension, to ‘The Birth of Ra’. Simple calculation shows that after 753 years (1506 ÷ 2 = 753 years, half the Great Solar Cycle), the ‘Birth of Ra’ had drifted to the

winter

solstice and thus a massive 54° to the south of the summer solstice sunrise point. In other words, in the year 2028 BC (2781-753 = 2028) the sun disc rose 28°

south

-of-east at the winter solstice and not, as it had done originally in 2781 BC, 28°

north

-of-east at the summer solstice. Surely this conjunction of ‘The Birth of Ra’ with the winter solstice, marked by the extreme southerly position of the sun disc on the horizon, must have had immense religious significance to the priests of the solar cult who were based in the southern extreme of Egypt. It must have seemed as if the cosmic order had ordained that now it was their turn to be controllers of the sun religion and that the reigning pharaoh should now also move the capital of the country from its location in the north to a new location in the south.

Is there any indication that this happened? If my hypothesis is correct, then we ought to find in the south of Egypt a major religious centre rising in prominence at around 2028 BC which not only was dedicated to this new vision of the sun-god but, more especially, whose principal sun temple was orientated to the winter solstice sunrise.

Amazing as it may seem, it was not until the late 1800s that European scholars began to suspect that the ancient temples of Egypt may have had astronomical alignments. And although it had long been known that the bases of the pyramids were aligned to the astronomical cardinal points, no one as yet had suspected that temples also had anything to do with the rising or setting of the sun or the stars. As we have seen, the consensus among Egyptologists was - and to a certain extent still is - that the temples of Egypt were simply made to face the Nile. But all this began to change - or should have done - one cold November evening in 1890, when the astronomer Sir Norman Lockyer read a carefully structured paper at the Royal School of Mines in London to a small audience of middle-aged gentlemen in white collar and black tie.

That evening Lockyer presented what he thought was a completely new and revolutionary idea: that the ancient temples of Egypt had all probably been aligned to the sun or the stars. He visualised the ancients who designed those temples not merely as superstitious priests but rather as

astronomer

s (albeit subjugated to their religion) who had cleverly incorporated their cosmologies and celestial myths into the orientation and symbolism of their religious buildings. It all seemed completely new and very controversial to the learned gentlemen listening to Lockyer - except for one, who, after the lecture, politely informed Locker by letter that a certain Professor Nissen in Germany had beaten him to it by publishing a paper on this topic not long ago. Clearly embarrassed by this news, but being the great gentleman and scholar that he was, Lockyer was later to write in the preface of his famous book,

The Dawn of Astronomy

, the following acknowledgement:

astronomer

s (albeit subjugated to their religion) who had cleverly incorporated their cosmologies and celestial myths into the orientation and symbolism of their religious buildings. It all seemed completely new and very controversial to the learned gentlemen listening to Lockyer - except for one, who, after the lecture, politely informed Locker by letter that a certain Professor Nissen in Germany had beaten him to it by publishing a paper on this topic not long ago. Clearly embarrassed by this news, but being the great gentleman and scholar that he was, Lockyer was later to write in the preface of his famous book,

The Dawn of Astronomy

, the following acknowledgement:

After my lectures were over, I received a very kind letter from one of my audience, pointing out to me that a friend had informed him that Professor Nissen, in Germany, had published some papers on the orientation of ancient temples. I at once ordered them. Before I received them I went to Egypt to make some inquiries on the spot with reference to certain points which it was necessary to investigate, for the reason that when the orientations were observed and recorded, it was not known what use would be made of them, and certain data required for my special inquiry were wanting. In Cairo also I worried my archaeological friends. I was told that the question had not been discussed; that, so far as they knew, the idea was new . . . One of them, Brugsch Bey, took much interest in the matter, and was good enough to look up some of the old inscriptions, and one day he told me he had found a very interesting one concerning the foundation of the temple at Edfu. From this inscription it was clear that the idea was not new, it was possibly six thousand years old. Afterwards I went up the river, and made some observations which carried conviction with them and strengthened the idea in my mind that for the orientation not only of Edfu, but of all the larger temples which I examined, there was an astronomical basis. I returned to England at the beginning of March, 1891, and within a few days of landing received Professor Nissen’s papers. I have thought it right to give this personal narrative, because, while it indicates the relation of my work to Professor Nissen’s, it enables me to make the acknowledgment that the credit of having first made the suggestion belongs, so far as I know, solely to him.

16

In spite of these scholarly niceties, it is Lockyer and not Nissen who has been accredited in the annals of science with the epithet ‘Father of Archaeoastronomy’ - that relatively new branch of archaeology that makes use of astronomy to study ancient temples and sacred sites.

Joseph Norman Lockyer was born in 1836 to a middle-class family in Rugby. He was educated at private schools in England and various parts of Europe, and as a young man worked at the War Office in London. It was there that he took an interest in astronomy, building a small observatory at his house in the leafy and fashionable suburb of Hampstead. It was thus, in this modest and quaint way, that Lockyer began his distinguished career in astronomy. By 1862 he had been elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, and two years later, after purchasing his first spectroscope, he was to direct his sharp brain to the study of solar emissions. In 1868, while working at the College of Chemistry in London, Lockyer observed the bright emissions from the sun during a total eclipse and concluded that they were from an unknown element which he named ‘helium’-a quarter of a century before Sir William Ramsay would isolate this gas in his laboratory. In 1885 Lockyer became the world’s first professor of astronomical physics.

17

There is another less known ‘first’ about Lockyer: in 1869 he collaborated with the publishers Macmillan & Company and founded the influential scientific journal

Nature

.

18

For his discovery of helium and his other achievements in science, Lockyer received a knighthood in 1897. An observatory and planetarium which he established at Salcombe Hill in Devonshire in 1912 with his son James still bear their names: ‘The Norman Lockyer Observatory and James Lockyer Planetarium’.

19

17

There is another less known ‘first’ about Lockyer: in 1869 he collaborated with the publishers Macmillan & Company and founded the influential scientific journal

Nature

.

18

For his discovery of helium and his other achievements in science, Lockyer received a knighthood in 1897. An observatory and planetarium which he established at Salcombe Hill in Devonshire in 1912 with his son James still bear their names: ‘The Norman Lockyer Observatory and James Lockyer Planetarium’.

19

It was in the autumn of 1890, at the mature age of 53, that Norman Lockyer began to take a keen interest in the astronomical alignments of ancient Egyptian temples.

20

He delved into the voluminous publications of Napoleon’s expedition of 1798 and the work of the Prussian expedition of 1844, but soon realised that neither had ‘paid any heed to the possible astronomical ideas of the temple builders’. Lockyer himself strongly suspected that ‘there was little doubt that astronomical consideration had a great deal to do with the direction towards which these temples faced’. So, in late November 1890, he decided to go to Egypt and see for himself. Upon his arrival in Cairo he reported to the antiquity authorities, which, at that time, were controlled by the German Egyptologist Emile Brugsch Bey.

21

It so happened that his older brother, the eminent professor Heinrich Brugsch Bey, was the acclaimed authority on the astronomical inscriptions found on ancient temples and tombs, and thus was only too happy to help Lockyer in his investigations.

22

It was from Brugsch’s inscriptions that Lockyer became aware of the ‘stretching of the cord’ ceremony, and he was quick to realise that it was a ritual describing the astronomical orientating of temples. Much encouraged by this, he travelled upriver to Luxor, a journey which in those days took nearly three weeks.

20

He delved into the voluminous publications of Napoleon’s expedition of 1798 and the work of the Prussian expedition of 1844, but soon realised that neither had ‘paid any heed to the possible astronomical ideas of the temple builders’. Lockyer himself strongly suspected that ‘there was little doubt that astronomical consideration had a great deal to do with the direction towards which these temples faced’. So, in late November 1890, he decided to go to Egypt and see for himself. Upon his arrival in Cairo he reported to the antiquity authorities, which, at that time, were controlled by the German Egyptologist Emile Brugsch Bey.

21

It so happened that his older brother, the eminent professor Heinrich Brugsch Bey, was the acclaimed authority on the astronomical inscriptions found on ancient temples and tombs, and thus was only too happy to help Lockyer in his investigations.

22

It was from Brugsch’s inscriptions that Lockyer became aware of the ‘stretching of the cord’ ceremony, and he was quick to realise that it was a ritual describing the astronomical orientating of temples. Much encouraged by this, he travelled upriver to Luxor, a journey which in those days took nearly three weeks.

Other books

Absolute Surrender by LeBlanc, Jenn

Happy Birthday, Mr Darcy by Victoria Connelly

More Than Life (Arcane Crossbreeds) by Vyne, Amanda

Ribblestrop Forever! by Andy Mulligan

Right Wolf, Right Time by Marie Harte

Different Roads by Clark, Lori L.

Moonlight Cove by Sherryl Woods

The Catcher's Mask by Matt Christopher, Bert Dodson

Lackey, Mercedes & Flint, Eric & Freer, Dave - [Heirs of Alexandria 01] by The Shadow of the Lion (v5.0) [html]

Harlan Ellison's Watching by Harlan Ellison, Leonard Maltin