The Egypt Code (25 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

So, did anything happen in 1321 BC that could be interpreted as the ‘return of the phoenix’ to Heliopolis? And if so, then from where was this ‘phoenix’ returning?

And who was the ‘phoenix’?

CHAPTER FIVE

The Return of the Phoenix

Afterwards I went up the river, and made some observations which

carried the conviction with them and strengthened the idea in my mind

that in the orientation not only of Edfu, but of all the large temples which

I examined, there was an astronomical basis.

Sir Norman Lockyer,

The Dawn of Astronomy

The Dawn of Astronomy

. . . strange to say, the whole number of buildings in stone, as yet known and examined, which were erected on both sides of the river by Egyptians and Ethiopian kings, furnish incontrovertible proof that the long series of temples, cities, sepulchres, and monuments in general, exhibit a distinct chronological order, of which the starting point is found in the pyramids, at the apex of the Delta.

H. Brugsch,

Egypt Under the Pharaohs

Egypt Under the Pharaohs

In modern European reckoning, when we travel north we use terminology such as ‘going up north’, while when travelling south we say ‘going down south’, without quite knowing why exactly. This concept comes, in fact, from the way that seventeenth-century cartographers decided to place north at the top of their maps. But there is no scientific reason for this. The earth is a globe floating, and all directions can be considered as being ‘up’ depending on how one chooses to perceive them. The decision to place north ‘up’ is just a choice and not a scientific reality, as all cartographers would agree. There is no good reason why south should not be placed at the top of a map if one wants it so. The ancient Egyptians decided that south rather than north was ‘up’ through observation of their world. South was ‘up’ because the Nile flowed

down

from the south, and because the sun reached its highest point at noon in the south. Indeed, the southern part of their country was perceived as ‘Upper Egypt’ and the northern part ‘Lower Egypt’.

1

down

from the south, and because the sun reached its highest point at noon in the south. Indeed, the southern part of their country was perceived as ‘Upper Egypt’ and the northern part ‘Lower Egypt’.

1

Another peculiarity of the Egyptian geography is that it has always been perceived not only as ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ but as two distinct lands. According to Egyptologists, the land we now call Egypt was very early divided into two distinct although united kingdoms, one in the north or in ‘Lower Egypt’ and the other in the south or ‘Upper Egypt’. In all guidebooks on Egypt you will be told unequivocally that in 3000 BC or thereabouts, a powerful king of Upper Egypt called Menes (or Narmer or Scorpion) invaded Lower Egypt and united it with Upper Egypt, thus creating the ‘Kingdom of the Two Lands’, a sort of pharaonic merger of north and south. You will also be told with the same assurance that Menes or Narmer or Scorpion built the capital of this double kingdom at Memphis, 15 kilometres south of modern Cairo. As I.E.S. Edwards, for example, explains:

Menes, at first king of Upper Egypt only, overcame the northern kingdom and united the two former kingdoms under one crown, established himself as ruler over the whole land. Memphis would thus have been the natural place for him to build a strong fortified city . . . In unifying the two kingdoms, Menes performed a military feat that may have been attempted by others before his time, but never with more than temporary success. Menes, however, both achieved the military victory necessary for uniting the two kingdoms and ensured that its effects would be lasting by following it up with an astute policy, on which the greatness of Egypt in the subsequent dynasties was founded. Nevertheless, the historical fact that Egypt had once consisted of two separate kingdoms was never entirely forgotten by its people, for down to the latest times the pharaohs still included among their titles that of ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt’.

2

Edwards, like many Egyptologists of his generation, seems to have accepted that the ‘unification’ of Upper and Lower Egypt was an actual historical event. There are, however, some Egyptologists who are not so sure of this, and consider it to have probably been a ‘semimythical anecdote’. For example, Michael Hoffman, who is an accredited authority on the predynastic history of ancient Egypt, insists that there is precious little contemporary evidence that supports a historical ‘unification’. According to Hoffman, the story of the ‘unification’ event ‘is culled from documents that come from hundreds if not thousands of years after the alleged event, by which time Menes, if he ever existed, had been transformed into a culture-hero whose life and accomplishments were embroidered with semi-mythical anecdotes.’

3

This is also the view of the Czech Egyptologist Miroslav Verner, who admits that ‘some researchers consider Menes a purely legendary figure’,

4

and of the influential Dr Jaromir Malek of the Griffith Institute, who went as far as to suggest that the origin of the idea of two separate kingdoms ‘may be a projection of the pervasive dualism of Egyptian ideologies, (and) not a record of a true historical situation’.

5

3

This is also the view of the Czech Egyptologist Miroslav Verner, who admits that ‘some researchers consider Menes a purely legendary figure’,

4

and of the influential Dr Jaromir Malek of the Griffith Institute, who went as far as to suggest that the origin of the idea of two separate kingdoms ‘may be a projection of the pervasive dualism of Egyptian ideologies, (and) not a record of a true historical situation’.

5

But if the ‘unification’ was not historical, then from where or from what did the ancient Egyptians themselves cull such a dualism for their country?

In the year 1800, during the French occupation of Egypt, a large black stone with rows of hieroglyphic inscriptions on it, was discovered in a field just a few kilometres south of modern Cairo by marauding French soldiers in Napoleon’s army. The black stone, which apparently had been used by local farmers to grind wheat, was at first kept in the army barracks at Alexandria, but when the French surrendered to the British forces in 1801, the mysterious stone was taken as spoils of war and promptly dispatched to Earl Spencer in England, who, probably not knowing what to make of it, eventually donated it to Egyptology. Today the black stone is displayed on the south wall of the ground floor of the Egyptian gallery at the British Museum in London. A rectangular block of granite measuring 92 x 137 cm, it has carved on it 64 lines of hieroglyphic text. Although much of the original inscription has been severely damaged through the ages, enough nonetheless remains to provide us with an invaluable insight into how the ancient Egyptians perceived the origins of their double kingdom of Upper and Lower Egypt and also the genesis of the ‘divine’ kings who ruled it. The text is known to Egyptologists as the Memphite Theology, and according to Frankfort, it mainly expounds a ‘theory of kingship’ based on a mythical ancestry.

6

The stone and the inscriptions on it date from about 750 BC during the reign of King Shabaka; hence its occasional name of the Shabaka Stone. But some Egyptologists believe that the text was culled from a much older source, which, in any case, is confirmed by the ancient scribe himself who copied it:

6

The stone and the inscriptions on it date from about 750 BC during the reign of King Shabaka; hence its occasional name of the Shabaka Stone. But some Egyptologists believe that the text was culled from a much older source, which, in any case, is confirmed by the ancient scribe himself who copied it:

This writing was copied out anew by his majesty (King Shabaka) in the house of his father Ptah-South-of-his-Wall (Memphis), for his majesty found it to be a work of the ancestors which was worm-eaten so that it could not be understood from beginning to end. His majesty copied it anew so that it became better than it had been before . . .

7

Egyptologist and philologist Miriam Lichtheim, who studied the writings on the Shabaka Stone, concluded that the ‘text is a work of the Old Kingdom but its precise date is not known. The language is archaic and resembles that of the Pyramid Texts.’

8

This view is shared by Frankfort, who was of the opinion that certain doctrines found in the Memphite Theology came from ‘traditions of the greatest antiquity’. Also according to Frankfort, ‘the text is a cosmology . . . it describe the order of creation and makes Egypt . . . an indissoluble part of the order’.

9

8

This view is shared by Frankfort, who was of the opinion that certain doctrines found in the Memphite Theology came from ‘traditions of the greatest antiquity’. Also according to Frankfort, ‘the text is a cosmology . . . it describe the order of creation and makes Egypt . . . an indissoluble part of the order’.

9

The first part of the inscriptions narrates how the creation of the land of Egypt had taken place when the primeval waters receded and the ‘Mound of Creation’ first appeared at Heliopolis. The story then moves quickly to the epic conflict between Horus, the son of Osiris, and his uncle the god Seth, over the legitimate right to rule Egypt. The conflict ends by being resolved by the earth-god Geb, father of Osiris, nonetheless under the aegis of the Council of Gods or Great Ennead:

Geb, Lord of the Gods, commanded that the Nine Gods gather to him. He judged between Horus and Seth; he ended their quarrel. He made Seth king of Upper Egypt in the land of Upper Egypt, up to the place where he was born which is Su (a place near Herakleopolis). And Geb made Horus king of Lower Egypt in the land of Lower Egypt, up to the place in which his father (Osiris) was drowned which is ‘Division of the Two Lands’ . Thus Horus stood over one region and Seth stood over one region. They made peace over the Two Lands at Ayan (near Memphis). That was the division of the Two Lands. Geb’s words to Seth: ‘Go to the place in which you were born.’ Seth: ‘Upper Egypt.’ Geb’s words to Horus: ‘Go to the place in which your father was drowned.’ Horus: ‘Lower Egypt.’ Geb’s words to Horus and Seth: ‘I have separated you’ into Lower and Upper Egypt. Then it seemed wrong to Geb that the portion of Horus was like the portion of Seth. So Geb gave to Horus Seth’s inheritance, for he is the son of his first born (Osiris). Geb to the Nine Gods: ‘I have appointed Horus, the firstborn.’ Geb’s words to the Nine Gods: ‘Him alone, Horus, the inheritance.’ Geb’s words to the Nine Gods: ‘To this heir, my inheritance.’ Geb’s words to the Nine Gods: ‘To the son of my son, Horus . . .’ Then Horus stood over the land. He is the uniter of this land, proclaimed in the great name: Ta-tenen, South of his Wall, Lord of Eternity. Then sprouted the two great magicians (crowns) upon his head. He is Horus, who arose as king of Upper and Lower Egypt, who united the Two Lands in the nome of the Wall (Memphis), the place in which the Two Lands were united. Reed and Papyrus were placed on the double door of the House of Ptah (a creator god). This means Horus and Seth, pacified and United. They fraternised so as to cease quarrelling in whatever place they might be, being united in the House of Ptah, the ‘Balance of the Two Lands’ in which Upper and Lower Egypt had been weighed. This is the land (of) the burial of Osiris

. . .

10

It does not require much imagination to see that the ‘unification’ of Upper and Lower Egypt as described in the Memphite Theology has both a mythical and a cosmic ring to it. The land of the ‘burial of Osiris’ which is the Memphite region is almost certainly also the Duat, the starry underworld containing Orion, which, as we have seen, is the celestial form of Osiris. Bearing this in mind, the words of the Canadian Egyptologist Samuel Mercer have a particular resonance when he informs us that ‘the Duat was a kind of duplicate of Egypt. There was an Upper and Lower Duat, and it had a great river running through it.’

11

11

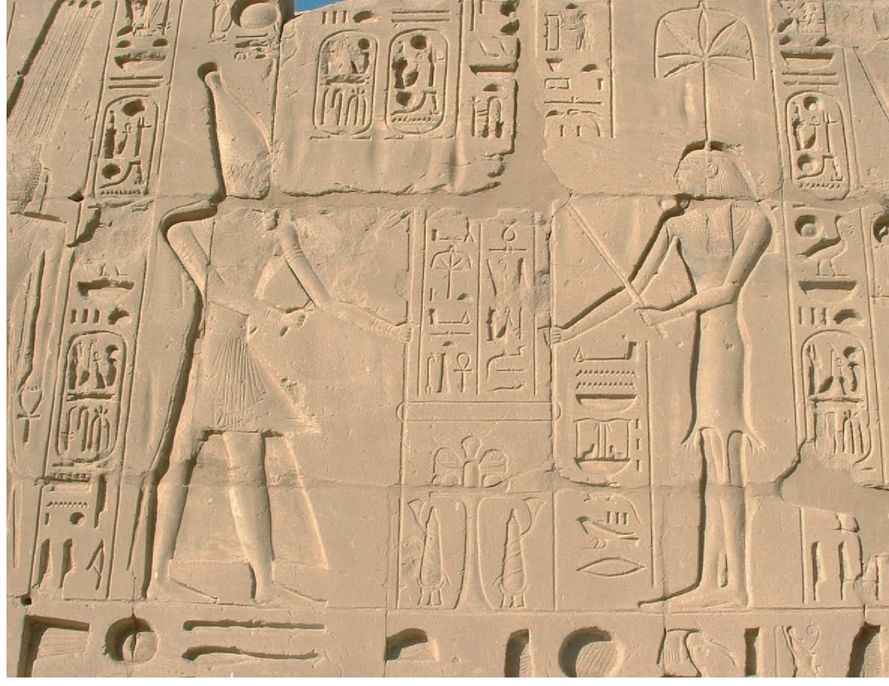

The King and Seshat performing the

Stretching

the Cord

ceremony, Temple of Karnak.

Stretching

the Cord

ceremony, Temple of Karnak.

Reconstruction of the

Stretching the Cord

ceremony, Hilversum Studios, Holland.

Stretching the Cord

ceremony, Hilversum Studios, Holland.

Other books

A Spark Unseen by Sharon Cameron

Sex with Kings by Eleanor Herman

River in the Sea by Tina Boscha

Alpha by Sophie Fleur

NYPD Red by James Patterson

Bones of Faerie by Janni Lee Simner

The Pilo Family Circus by Elliott, Will

The Wolfen by Strieber, Whitley

Anita Mills by The Fire, the Fury