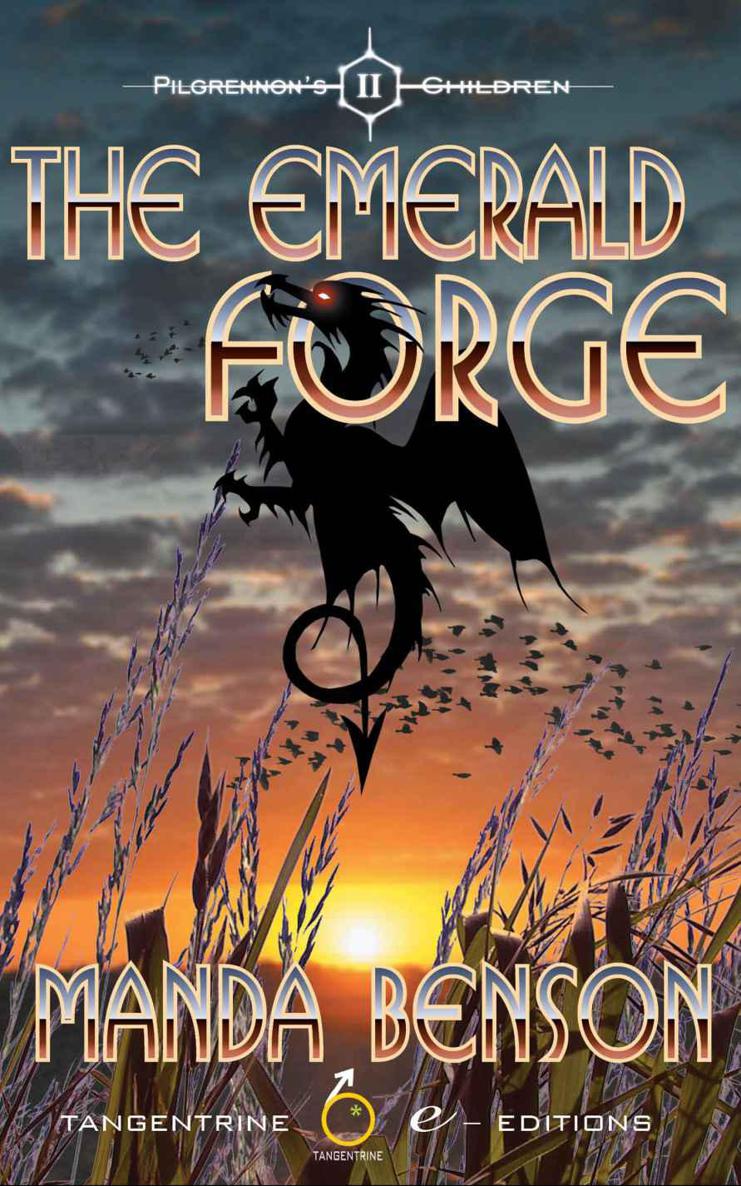

The Emerald Forge (Pilgrennon's Children)

Read The Emerald Forge (Pilgrennon's Children) Online

Authors: Manda Benson

The Emerald Forge

Electronic edition

Published by Tangentrine Ltd

Copyright © 2012 Manda Benson

Manda Benson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

This novel is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to locations, incidents, or persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

ISBN (electronic edition): 978-0-9566080-8-6

The Emerald Forge is also available in print

ISBN (print): 978-0-9566080-7-9

Great effort has been taken in the production of this e-book and in ensuring it is made available at a reasonable price and without intrusive copy protection.

Electronic piracy harms writers and the publishing industry

Please buy e-books only from publisher-approved vendors.

If you think you may have acquired this e-book from an illegal source, please email [email protected], quoting the URL where you downloaded it.

Contents

The Emerald Forge

Appendix

The Emerald Forge

by Manda Benson

With thanks to

J.D. Williams and D.J.Cockburn

-1-

T

HE

graffiti must have gone up last night. Dana would never have missed this if she’d walked past it yesterday.

A roiling black-and-grey mushroom cloud took up the entire wall, its underside shot through with veins of red flame, upon a background of an infernal red sky and a desolate plain of blackened buildings and burned trees. In the foreground of the panorama, uplit by a red glow and with hair appearing to flow in the hot breeze, had been painted the head and shoulders of a woman with an exaggerated cartoon expression of demonic glee. Her fist was raised in triumph, her face sinister behind dark glasses.

It always hit Dana with a stab of longing and apprehension whenever she recognised Jananin Blake’s face on a newspaper or public wall, or when she heard her voice on the radio or television. It wasn’t easing over time, either.

If anything, it got harder.

The painting must be one of Boggsy’s. Yes, Dana could just make out the cursive signature with the long, curled tail on the

y

on the bottom right corner, highlighted in white against Jananin’s shoulder. Boggsy didn’t like Jananin. Indeed, Boggsy didn’t seem to like any of the Spokesmen for the Meritocracy. Graeme used to say Boggsy was like a mirror, reflecting the Spokesmen’s opinions without their high talk. In the last two annual Spokesmen’s referenda, people had even voted for Boggsy enough that he― or she — could have claimed a position as Spokesman, but Boggsy was anonymous and had never come forward to claim or reject that right.

Dana took a few steps back onto the grass bank so she could see the image in its entirety. Mentally, she drew a rectangle around it and remembered it as a digital photograph. She’d transfer it to a computer when she got home.

There was a plaque at the bottom of the wall. Dana couldn’t read it from this distance, but she knew it had a statement on it saying the surface was a public wall for the expression of the opinions of the public, and something about it being a criminal offence to prevent people from using it, because it was treason to censor the Meritocracy.

Cool pinpricks had begun to flick Dana’s face and hands. A sparse rain rustled the dry grass. She glanced up to the sky, and at the path behind her. A boy was coming this way, but he was still some distance behind. A tall, fat boy, with thick plastic-framed glasses and dark brown hair cut in a puddingbowl style. The bottom of his shirt hung crumpled over his trousers, and he wore the green-and-gold striped tie of Dana’s school, tied so the narrow end was short and the tie so ridiculously long it hung to his knees. He had his coat slung over one shoulder by a finger and carried his school bag on the other arm.

Earlier that day, Dana had been trying to get through a crowded stairwell to go upstairs to Chemistry, and some older boys had yelled “

Falcon Punch

!” and shoved a fat boy into her, and laughed and jeered as though pushing fat boys into smaller girls was a new sport. The boy had stared at her before the motion of the throng pulled him out of sight. This boy looked similar, but Dana wasn’t very good at recognising people, especially people whom she’d seen only once. It could be the boy was angry with her for being there and making him look bad in front of his friends. It hardly made sense, as it wasn’t

her

fault, but then people rarely did make much sense at school. Best to leave now, and avoid the chance of anything happening.

She didn’t look behind as she continued on the path, but she could hear the boy’s footsteps, and his presence just a few paces behind made her nervous. She didn’t like that boy walking there, able to see her.

Dana’s route home brought her through an avenue with cherry trees edging the driveways, and at the end of this avenue was a gate that led to a field of common land and a copse: an alternative route to Pauline and Graeme’s house. She would feel much more at ease in the quiet wood with the bird song and the rustle of the trees instead of the noise of traffic and people, and that boy behind her. Dana passed quickly beneath the branches of the cherry trees, climbed up onto the metal stile, and jumped down into the field. She set off across the wet grass confidently, not looking back.

The rattle of the gate behind told her she was followed.

Dana hurried along the uneven path worn in the grass beside the allotments that backed onto the field. A piebald dog behind the hedge barked, making her jump and quicken her pace. The boy had to be following her. Why else would he be coming this way? Dana didn’t dare look back. She broke into a run as she reached the bottom of the path. Her course took her across wet grass and under the cover of the trees. She scrambled up the gap worn through the undergrowth and glanced back as she turned onto the main path. The boy was still behind her. She ran. When she looked back, he still followed, slower than her. Perhaps she could outrun him. Dana knew these woods well, although Pauline was always telling her not to go into them because there might be murderers and rapists lurking there. If she could get enough of a headstart and break off the path, perhaps she could hide in the wood until he’d gone.

She ran on until the path turned a corner and trees blocked the sight of her pursuer, and leapt down off the path. Her foot landed wrong in the soft soil, her ankle twisted, and sky and ground turned over. Dana sat up, heart pounding. The boy hadn’t caught up with her yet, but a nettle had got her on the wrist. She’d pulled in her hands instinctively when she had fallen, and aside from her ankle she couldn’t feel that she was hurt anywhere else. A large tree trunk stood not far from where she had fallen, bracts of burgundy-and-purple-striped fungi sprouting from it. Her ankle ached as she staggered behind the tree and crouched down. From here she could see the wood of the tree was decomposed and spongy, and its core had rotted away to leave an uneven crater formed from its outermost layers of bark. Keeping her knees bent into a crouching position, she crept inside the hollow and looked through a crack in the wood up onto the path.

Presently the boy appeared. He looked about the path ahead, apparently confused, and turned slowly through 360 degrees to scan the woods. Dana steadied her breathing― the boy was standing not ten yards from her, and he might hear it. She felt safe, ensconced inside the dead tree with the smell of mould and soil surrounding her, and she began to think derisive things about the boy, as she often did about people who bullied her. He was a fat, ugly boy, Dana thought, and probably a stupid boy as well from the look of him. He had a double chin and a spotty face, and he was sweating copiously from a brisk walk and a five-minute run on a summer afternoon. The perspiration had wetted his school shirt, and he had breasts like a girl.

The boy was looking at the ground in front of the path. She must have flattened the ferns when she’d fallen. He lifted his head and his eyes looked straight at Dana. Perhaps the boy wasn’t as stupid as he looked.

The boy put one foot down off the path. He was coming. For a moment, Dana was paralysed. Then she turned and broke from her hiding place and ran down the hill.

“Oi!

Oi

!” the boy shouted. Dana could hear him crashing through the undergrowth behind her. She ignored the stiff pain in her ankle and weaved her way through brambles, pulling the sleeves of her school jersey over her fists to protect skin and pushing tall stems apart with her arms. She was faster and more agile than the boy chasing her, but quickly she began to see he had other things on his side. She had to use effort to force her passage through the vegetation, whilst he simply followed in the trail she had cleared, and his physical bulk gave him more inertia on the downhill run and made it easier for him to trample anything that did get in his way.