The Enchanter

Authors: Vladimir Nabokov

Praise for

The Enchanter

“A tale of crime and punishment … a foretaste of one of this century’s great novels.”

—Wall Street Journal

“The Enchanter

is an alarming, sensuous and shimmering forerunner of

Lolita

.… It is a delight to have this early version of Nabokov’s strange, compelling fantasy.”

—USA Today

“Sensuous, amusing, scary … Nabokov lifts [

The Enchanter

] through the exhilarating artistry of his poetic and explicit language.”

—Boston Herald

“[

The Enchanter

is] in the top class of Nabokov’s work.”

—John Bayley,

Spectator

(London)

“Elegantly written and exquisitely shaped.”

—The Sunday Times

(London)

“The Enchanter

exhibits all of [Nabokov’s] cunning and exactness of execution.…

The Enchanter

will indeed enchant.”

—Listener

(London)

“One of the most exciting novellas ever written, Nabokov near, or at least clearly anticipating, his very best.”

—Literary Review

(London)

First Vintage International Edition, July 1991

Copyright © 1986 by Dmitri Nabokov

Author’s Note One copyright © 1957 by Vladimir Nabokov

Author’s Note Two copyright © 1986 by Article 3C Trust

under the Will of Vladimir Nabokov

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, in 1986.

The Enchanter

is translated from Vladimir Nabokov’s unpublished work entitled

Volshebnik

. Copyrights in

Volshebnik

are held by Dmitri Nabokov as trustee of Article 3C Trust under the Will of Vladimir Nabokov. This edition published by arrangement with the Estate of Vladimir Nabokov.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich, 1899–1977.

[Volshebnik. English]

The enchanter / Vladimir Nabokov ; translated by Dmitri Nabokov.

p. cm. —(Vintage international)

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Putnam, c1986.

Translation of: Volshebnik.

eISBN: 978-0-307-78730-9

I. Title.

PG3476.N3V5513 1991

891.73′42—dc20 90-55704

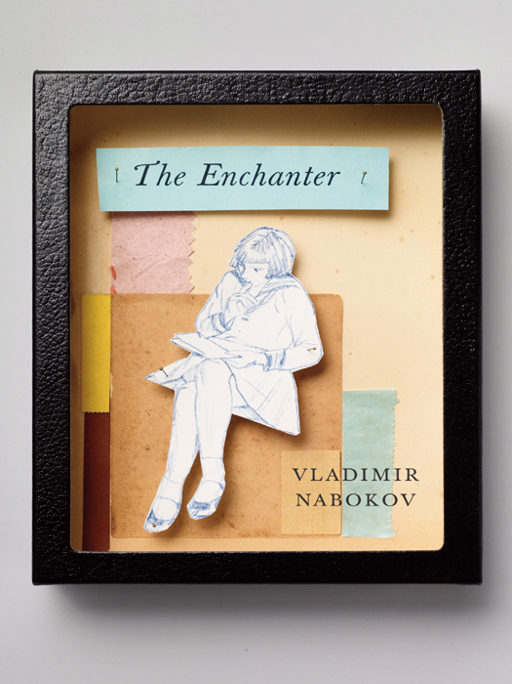

Cover art by Megan Wilson and Duncan Hannah

Cover photograph by Alison Gootee

v3.1

To Véra

CONTENTS

On a Book Entitled

The Enchanter

by Dmitri Nabokov

AUTHOR’S NOTE ONE

1

T

HE FIRST LITTLE THROB

of

Lolita

went through me late in 1939 or early in 1940

2

in Paris, at a time when I was laid up with a severe attack of intercostal neuralgia. As far as I can recall, the initial shiver of inspiration was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage. The impulse I record had no textual connection with the ensuing train of thought, which resulted, however, in a prototype of my present novel, a short story some thirty pages long.

3

I wrote it in Russian, the language in which I had been writing novels since 1924 (the best of these are not translated into English,

4

and all are prohibited for political reasons in Russia

5

). The man was a central European, the anonymous nymphet was French, and the loci were Paris and Provence. [A brief synopsis of the plot follows, wherein Nabokov names the protagonist: he thought of him as Arthur, a name that may have appeared in some long-lost draft but is mentioned nowhere in the only known manuscript.] I read the story one blue-papered

6

wartime night to a group of friends—Mark Aldanov, two social revolutionaries,

7

and a woman doctor

8

; but I was not pleased with the thing and destroyed it sometime after moving to America in 1940.

Around 1949, in Ithaca, upstate New York, the throbbing, which had never quite ceased, began to plague me again. Combination joined inspiration with fresh zest and involved me in a new treatment of the theme, this time in English—the language of my first governess in St. Petersburg, circa 1903, a Miss Rachel Home. The nymphet, now with a dash of Irish blood, was really much the same lass, and the basic marrying-her-mother idea also subsisted; but otherwise the thing was new and had grown in secret the claws and wings of a novel.

V

LADIMIR

N

ABOKOV

1956

1.

Excerpt from “On a Book Entitled

Lolita”

originally published in French in

L’Affaire Lolita

, Paris, Olympia, 1957, and subsequently appended to the novel.

2.

It has been established from the manuscript of

The Enchanter

that the year was 1939.

3.

Father had not seen the story for years, and his recollection had telescoped its length somewhat.

4.

This has since been remedied.

5.

This was true until July 1986, when the Soviet literary establishment apparently realized at last that Socialist Realism and artistic reality do not necessarily coincide, and an organ of that establishment took a sharply angled turn with the announcement that “it is high time to return V. Nabokov to our readers.”

6.

As an air-raid precaution.

7.

Vladimir Zenzinov and Ilya Fondaminsky.

8.

Madame Kogan-Bernstein.

AUTHOR’S NOTE TWO

1

As I

EXPLAINED

in my essay appended to

Lolita

, I had written a kind of pre

-Lolita

novella in the autumn of 1939 in Paris. I was sure I had destroyed it long ago but today, as Vera and I were collecting some additional material to give to the Library of Congress, a single copy of the story turned up. My first movement was to deposit it (and a batch of index cards with unused

Lolita

material) at the L. of C., but then something else occurred to me.

The thing is a story of fifty-five typewritten pages in Russian, entitled

Volshebnik

(“The Enchanter”). Now that my creative connection with

Lolita

is broken, I have reread

Volshebnik

with considerably more pleasure than I experienced when recalling it as a dead scrap during my work on

Lolita

. It is a beautiful piece of Russian prose, precise and lucid, and with a little care could be done into English by the Nabokovs.

V

LADIMIR

N

ABOKOV

1959

1.

Excerpt from a letter of 6 February 1959, in which Nabokov proposed

The Enchanter

to Walter Minton, then president of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Minton’s reply expressed keen interest, but apparently the manuscript was never sent. Father was engrossed at the time in

Eugene Onegin, Ada

, the

Lolita

screenplay, and checking my translation of

Invitation to a Beheading

. He probably decided there was no room in his schedule for an additional project.

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

I

N THE INTEREST

of clarifying certain concentrated images (some of which originally stumped me too), and of providing the curious reader with a few informative sidelights, I have prepared a short commentary. In the interest of letting the reader get on with the story, I have placed my comments at the end and have, with one exception, avoided the distraction of footnotes in the text itself.

The Enchanter

H

OW CAN I COME TO TERMS

with myself?” he thought, when he did any thinking at all. “This cannot be lechery. Coarse carnality is omnivorous; the subtle kind presupposes eventual satiation. So what if I did have five or six normal affairs—how can one compare their insipid randomness with my unique flame? What is the answer? It certainly isn’t like the arithmetic of Oriental debauchery, where the tenderness of the prey is inversely proportional to its age. Oh, no, to me it’s not a degree of a generic whole, but something totally divorced from the generic, something that is not

more

valuable but

in

valuable. What is it then? Sickness, criminality? And is it compatible with conscience and shame, with squeamishness and fear, with self-control and sensitivity? For I cannot even consider the thought of causing pain or provoking unforgettable revulsion. Nonsense—I’m no ravisher. The limitations I have established for my yearning, the masks I invent for it when, in real life, I conjure up an absolutely invisible method of sating my passion, have a providential sophistry. I am a pickpocket, not a burglar. Although, perhaps, on a circular island, with my little female Friday …(it would not be a question of mere safety, but a license to grow savage—or is the circle a vicious one, with a palm tree at its center?).

“Knowing, rationally, that the Euphrates apricot

1

is harmful only in canned form; that sin is inseparable from civic custom; that all hygienes have their hyenas; knowing, moreover, that this selfsame rationality is not averse to vulgarizing that to which it is otherwise denied access … I now discard all that and ascend to a higher plane.

“What if the way to true bliss is indeed through a still delicate membrane, before it has had time to harden, become overgrown, lose the fragrance and the shimmer through which one penetrates to the throbbing star of that bliss? Even within these limitations I proceed with

a refined selectivity; I’m not attracted to every schoolgirl that comes along, far from it—how many one sees, on a gray morning street, that are husky, or skinny, or have a necklace of pimples or wear spectacles—

those

kinds interest me as little, in the amorous sense, as a lumpy female acquaintance might interest someone else. In any case, independently of any special sensations, I feel at home with children in general, in all simplicity; I know that I would be a most loving father in the common sense of the word, and to this day cannot decide whether this is a natural complement or a demonic contradiction.

“Here I invoke the law of degrees that I repudiated where I found it insulting: often I have tried to catch myself in the transition from one kind of tenderness to the other, from the simple to the special, and would very much like to know whether they are mutually exclusive, whether they must, after all, be assigned to different genera, or whether one is a rare flowering of the other on the Walpurgis Night of my murky soul; for, if they are two separate entities, then there must be two separate kinds of beauty, and the aesthetic sense, invited to dinner, sits down with a crash between two chairs (the fate of any dualism). On the other hand, the return journey, from the special to the simple, I find somewhat more comprehensible: the former is subtracted, as it were, at the moment it is quenched, and that would seem to indicate that the sum of sensations is indeed homogeneous, if in fact

the rules of arithmetic are applicable here. It is a strange, strange thing—and strangest of all, perhaps, is that, under the pretext of discussing something remarkable, I am merely seeking justification for my guilt.”