The Eternal Flame (22 page)

Authors: Greg Egan

Tags: #Science Fiction, #General, #Space Opera, #Fiction

“Either my first target’s died, or something on the window obscured it,” Ada explained.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” Tamara was confused. They needed to communicate everything clearly, but Ada knew that perfectly well. In all of the drills, she’d been scrupulous.

“Ivo was telling us about his injuries, I didn’t want to interrupt him.”

“But once he’d stopped—”

“I know,” Ada said. “I apologize.” Her tone was even, with no trace of resentment, but Tamara still felt awkward to be reprimanding her.

There were contingency plans for all the observations to be performed out on the hull if there was serious damage to the windows from an encounter with orthogonal dust, but that was an extreme measure that would make the whole procedure much more arduous. Stray particles from the

Gnat

’s own exhaust might have left a smattering of subtle defects in the clearstone, but Tamara had never really thought through the proper response to such a minor vitiation.

“Once we’ve finished with the beacons, we should do a systematic check for pitting,” she decided.

“Good idea,” Ada said. A moment later she added, “Ah, first sighting acquired! Within the expected region.”

An ache in Ivo’s arm. A few flaws on a window pane.

Tamara had no intention of becoming complacent, but these were the kind of problems she could live with. In the drills, they’d rehearsed the complete disintegration of the

Gnat

’s cabin, flailing around the mock-up in their cooling bags until they’d learned to use their air cylinders as rockets to bring themselves together on the engine module, ready to make the flight home without a single wall to protect them. She should not be unsettled by anything less.

When they’d both computed their estimates of the

Gnat

’s trajectory, Tamara’s agreed with Ada’s to within the error bounds. The results implied that they would need to fire the engines again, briefly, in order to aim the

Gnat

squarely at the rendezvous point, but they could refine their measurements even further by waiting a few bells before repeating them.

To quantify the pitting on the windows, they each made observations of two gross stars that should have been visible from their respective posts, checking for any images that were obscured or distorted. Tamara found two cases where she could see a faint, blurred oval of light in place of a portion of one of the star trails—and by shifting the theodolite sideways while retaining its direction, she could move this aberration across the field, a sure sign that the flaw was in the window itself.

Ada found three. It was not a bad rate. And when the beacon Ada had missed was due to repeat, they were able to use the trajectory data to anticipate its location in the sky much more precisely. This time it did show up, in the dead center of the targeted star field. Whatever the original problem had been, the navigational procedure itself was proving to be as robust as Tamara had hoped.

Carla fetched four loaves from the storage cupboard and the whole crew ate together. The women had agreed to double their usual food intake; they could return to fasting once the mission was over, but for now nothing mattered more than a clear head.

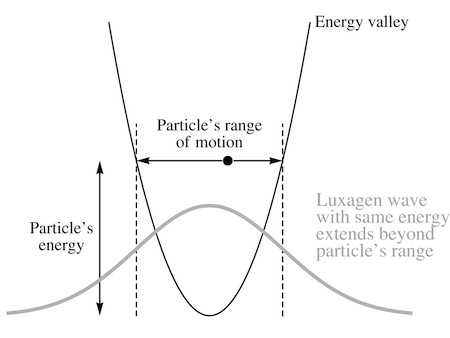

“I’ve been thinking about your luxagen waves,” Ivo told Carla. “They’re not confined entirely to the energy valleys, are they?”

“Not entirely,” Carla agreed. “The bulk of the wave lies in the part of the valley where a particle with the same energy would be rolling back and forth—but at the point where the particle would come to a halt and move back toward the center, the wave doesn’t instantly drop to zero. It just becomes weaker as you follow it out past that point.”

She sketched an illustration, but no one could see it clearly in the starlight so Tamara lit a small lantern and aimed the beam at Carla’s chest.

“And the same is true for a luxagen outside the valley, trying to get in?” Ivo wondered. “The energy ridge around the top of the valley won’t keep out a luxagen wave entirely—even if that ridge would be insurmountable to a particle with the same energy?”

“Right,” Carla said. “Energy barriers aren’t absolute for these waves, the way they are for particles.”

Ivo chewed on his loaf for a while, thinking this over. “Then why are solids stable under pressure?”

“Under pressure?”

“You’ve solved the original stability problem,” Ivo said. “You’ve explained why luxagens in a solid don’t gain energy by radiating, which would blow the whole structure apart. But there’s another problem now: if you squeeze a solid hard enough, why doesn’t it collapse? With the old particle mechanics you could expect the energy ridge between two valleys to keep the neighboring luxagens out. But if a luxagen wave has some probability of getting past that ridge, then over time, under pressure, shouldn’t the luxagens be squeezed together into fewer and fewer valleys? Shouldn’t the rock at the center of every world end up as a tiny, dense core too small to see?”

Carla said, “If you pack more luxagens into each valley, the ridges grow higher, making it harder for the waves to get past them. But the valleys do grow deeper as well, which will help to draw the waves in. I’m not sure if those two effects balance out…”

“And the gravitational pressure grows stronger, as the rock becomes more dense,” Ivo added.

“Yes. So it’s complicated. Let me do some calculations when we get back to the

Peerless

.”

“Hmm.” Ivo seemed pleased that Carla had no immediate answer to his puzzle. “And in spite of all these new ideas, the power of orthogonal matter to act as a liberator remains as mysterious as ever.”

“It does.” Carla was beginning to sound a bit besieged. “An ordinary, plant-derived liberator must have a distinctive shape that allows it to bind to a particular solid and modify its energy levels—rearranging the rungs on the ladder so a luxagen can climb all the way to freedom, radiating just one photon at a time. A rare fifth- or sixth-order phenomenon becomes a first-order event; a faint trickle of light over eons becomes an instantaneous avalanche.

“But what are the chances that the orthogonal dust that fell on the

Peerless

before the spin-up had just the right geometry needed to modify the energy levels of calmstone? If you pick some mineral at random, that certainly won’t do the job. If you swap its positive luxagens for negative ones, its structure will be exactly the same as the original. It might interact with ordinary calmstone a bit differently—each will see the other’s energy valleys as peaks, and vice versa, so grains of the two minerals might stick together half a wavelength closer than usual—but that would still be a weak and distant bond. So I don’t see how it could compare to the kind of chemical tricks that plants took eons to learn… and in fact, no plant ever gave us a liberator for calmstone.”

Ada said, “How elusive can the answer be, once we have a mountain of orthogonal matter to play with?”

“We’ve been playing with ordinary matter for generations,” Tamara pointed out. “And we don’t have all the answers there.”

“If the Object turns out to be inert,” Carla argued, “that could mean that we do understand both kinds of matter reasonably well. We’ll just be left with the historical curiosity of the dust that threatened to light up the

Peerless

… and I suppose that could turn out to have been some kind of freakish bad luck.”

Tamara wasn’t inclined to argue when she had no better ideas herself. But she did not believe in that kind of luck.

Tamara gathered six new beacon sightings, then merged them with Ada’s to sharpen their estimate of the

Gnat

’s trajectory. A few brief squirts of air from the attitude-control jets reoriented the craft so the engines could deliver a small push in the required direction. She set the parameters of the burn into the controlling clockwork, then the crew donned their helmets and strapped themselves into their couches again.

The glare from the exhaust through the windows was as bright as it had been at the launch, but Tamara had barely registered her weight against the couch when the burn was over. She’d been worried that using the engines again might exacerbate Ivo’s problem, but he assured her that he was completely unharmed this time.

A bell later, the observations showed their modified trajectory to be as good as they could have wished for. There was no point trying to aim the

Gnat

down to the last saunter yet, when they still hadn’t pinned down the rock they were aspiring to reach with the same precision. The infrared color trails taken from the

Peerless

could only tell them so much—but they’d soon be able to make a fresh determination of the Object’s trajectory, with the aid of some decent parallax at last.

Looking out at the familiar stars, Tamara realized that she’d never even searched the sky for the

Peerless

. It would have been invisible to the naked eye, but she’d felt no urge to hunt for it, no pang of separation at its disappearance. And why should she have felt lost? The light from the beacons and the stars formed a grid of intangible guide ropes, transforming the void around the mountain into a solid, traversable realm.

If they could find a way to hold this ground, building a permanent framework of beacons and observatories, the sky from the

Peerless

need never be flat again—need never revert to the kind of painted dome that befitted a pre-scientific culture. Whatever triumphs or disappointments the Object had in store, if they could just retain the hard-won benefits of parallax, at least her generation would have that much to its name.

“Four different kinds of rock, at least!” Ada declared excitedly. “Different hues, different textures, different albedos.”

Tamara hung back and let Carla and Ivo take their turns at the telescope first. She didn’t mind waiting, listening to their descriptions before she saw the image; it was like savoring the odor of a seasoned loaf for as long as possible before finally taking a bite.

“The more variegated the better,” Ivo said, squinting through the eyepiece. “Ah… wouldn’t it be perfect if just one of these minerals set calmstone on fire, and the others were inert? Then Silvano could have his new farms out here, alongside the liberator mines.”

He moved aside, and Tamara prepared to take his place. From the

Peerless

, the best view of the Object had given them its rough dimensions but little else. For two days now, she and Ada had been tracking it through their theodolites, treating successive locations of the blurred ellipse as one more set of navigational data, their sightings building up to a family of lines that would complete the elegant geometrical construction that made the rendezvous possible. But now they were close enough for the

Gnat

’s largest telescope—barely the size of Tamara’s own body—to show her the whole point of the exercise.

Tamara closed three eyes and pressed the fourth to the instrument. The ellipse was now a crisply rendered, idiosyncratic oval with a pinched and tilted waist. About a third of one lobe was as red as firestone, but the rest bore patches of brown, of gray and of white. Everything was pale and subdued in the starlight—and any comparisons she made with the sight of mineral samples in a well-lit workshop or storeroom would be unreliable—but the brown outcrops more or less matched the calmstone slopes of the

Peerless

, viewed under similar conditions. There was a sprinkling of small impact craters everywhere—structures Tamara had only ever seen before as sketches in astronomy books, recorded by the ancestors when they’d observed the inner planet Pio.

“We finally have our own sister world,” she said.

“Sister or co?” Ada replied.

“It almost matches us in size,” Carla pointed out. “A co should be smaller.”

Ivo said, “It’s what happens when the two come together that counts.”

“Either way,” Tamara said, “it doesn’t look like a stranger.” After three generations alone in the void, the travelers could hardly dismiss any companion as mundane. But these rocks did appear to be ordinary rocks, old and pitted as they were after a long journey. If their origins really could be traced all the way around the history of the cosmos, back to the primal world’s past-directed disintegration, that only made their similarity to the stuff of the

Peerless

all the more striking. Matter was matter, shaped by the same rules and forces everywhere—and it looked no different even when you encountered it backward.

Two small burns nudged the

Gnat

’s trajectory toward the rendezvous point. The crew kept returning to the telescope as the Object’s slow spin revealed its whole surface: more of the same minerals, more small craters.

“The only thing missing is life,” Carla said. “Not one patch of weed, not one speck of moss.”

“Pio, Gemma and Gemmo were dead worlds too,” Tamara reminded her. “Chemistry might be universal, but life must still be rare.”

Ivo took his turn at the eyepiece. “Forget life,” he said. “I’d be happy with any sign of rubble.”

Tamara felt the same. If the Object had been nothing but a loose pile of stones then they would have had no hope of altering its trajectory—but enough fragmentation to save Ivo from having to chip off samples himself would be a huge advantage. The Object’s spin was slow enough that even its weak gravity could, in theory, maintain a tenuous grip on pebbles scattered across its surface, but the creation and persistence of such things would depend on the whole detailed history of the body. Over time, the radiation pressure of starlight should have pushed away the very tiniest dust grains, but that was no loss: anything too small to see and avoid would only have posed a hazard.