The Eyes of the Dragon (36 page)

Read The Eyes of the Dragon Online

Authors: Stephen King

Was a day too long to wait?

Perhaps. Perhaps not.

Peter was torn in an agony of indecision. Ben . . . Thomas . . . Flagg . . . Peyna . . . Dennis . . . they whirled in his brain like figures seen in a dream. What should he do?

In the end, it was the appearance of the note itselfânot what was in itâthat persuaded him. For it to come this way, pinned to a napkin on the very night he meant to try his rope made of napkins . . . it meant he should wait. But only for a night. Ben would not be able to help.

Could

Dennis

help him, though? What could he do?

Dennis

help him, though? What could he do?

And suddenly, in a flash of light, an idea came to him.

Peter had been sitting on his bed, hunched over the note, his brows furrowed. Now he straightened up, his eyes alight.

His eyes fell on the note again.

If You have something on which You can rite, then throe down a Note and I will try to retreeve It late this Night.

Yes, of course, he had something to write on. Not the napkin itself, because it might be missed. Not Dennis's note, either, because it was written on both sides, from side to side and top to bottom.

But Valera's parchment was not.

Peter went back into his sitting room. He glanced at the door and saw that the spyhole was closed. Dimly he could hear the warders at cards below. He crossed to the window and waved twice, hoping that Dennis was really out there somewhere, and could see him. He would just have to hope so.

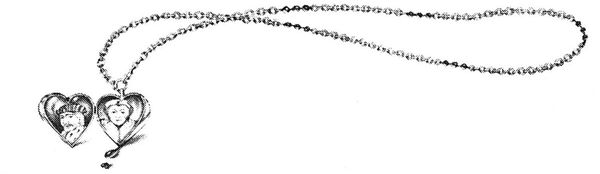

Peter went back to the bedroom, pulled up the loose stone, and after some reaching and fumbling, retrieved the locket and the parchment. He turned the parchment over to the blank side . . . but what was he to do for ink?

After a moment the answer came to him. The same thing Valera had done, of course.

Peter worked at his thin straw mattress, and after some tugging opened a seam. The stuffing was of straw, and before long, he had found a number of good long stalks that would serve as pens. Then he opened the locket. It was in the shape of a heart, and the point at the bottom was sharp. Peter closed his eyes for a moment and said a brief prayer. Then he opened them and drew the point of the locket across his wrist. Blood welled up at onceâmuch more than had come from the pinprick earlier. He dipped the first straw in his blood and began to write.

102

S

tanding in the cold darkness across the Plaza, Dennis saw Peter's shape come to the small window at the top of the Needle. He saw Peter raise his arms over his head and cross them twice. There would be a message, then. It doubledâno, trebledâhis risk, but he was glad.

tanding in the cold darkness across the Plaza, Dennis saw Peter's shape come to the small window at the top of the Needle. He saw Peter raise his arms over his head and cross them twice. There would be a message, then. It doubledâno, trebledâhis risk, but he was glad.

He settled in to wait, feeling numbness slowly creep over his feet and kill the feeling in them. The wait seemed very long. The Crier called ten . . . then eleven . . . finally twelve o' the clock. The clouds had hidden the moon, but the air seemed strangely lightâanother sign of a coming storm.

He was beginning to think that Peter must have forgotten him, or changed his mind, when that shape came to the window again. Dennis straightened up, wincing at a pain in his neck, which had been cocked upward for the last four hours. He thought he saw something arc out . . . and then Peter's shape left the high window. A moment later, the light up there was extinguished.

Dennis looked left and right, saw no one, took all of his courage in his hands, and ran out into the Plaza. He knew perfectly well that there might be someoneâa more alert Guard o' the Watch than last night's tuneless singer, for instanceâwhom he

hadn't seen,

but there was nothing to be done about that. He was also gruesomely aware of all the men and women who had been beheaded not far from here. What if their ghosts were still around, lurkingâ?

hadn't seen,

but there was nothing to be done about that. He was also gruesomely aware of all the men and women who had been beheaded not far from here. What if their ghosts were still around, lurkingâ?

But thinking about such things did no good, and so he tried to put them from his mind. Of more immediate concern was just finding the thing that Peter had thrown. The area at the foot of the Needle below Peter's window was a featureless white snowfield.

Feeling horribly exposed, Dennis began to cast about like an inept hunting dog. He wasn't sure what he had seen glimmering in the airâit had been there only for a secondâbut it had looked solid. That made sense; Peter would not have thrown a piece of paper, which might have fluttered anywhere. But what, and where was it?

As the seconds ticked by, turning into minutes, Dennis began to feel more and more frantic. He dropped to his hands and knees and began to crawl about, peering into footprints which had melted to the size of dragon prints earlier that day and which were now refreezing, hard and blue and shiny. Sweat coursed down his face. And he began to be deviled by a recurring ideaâthat a hand would fall on his shoulder, and when he turned he would see the grinning face of the King's magician inside his dark cowl.

A little late for hide and seek, isn't it, Dennis? Flagg would say, and although his grin would widen, his eyes would burn a baleful, hellish red. What have you lost? Can I help you find it?

Don't think his name! For the gods' sake, don't think his name!

But it was hard to stop. Where was it? Oh, where was it?

Back and forth Dennis crawled, his hands now as numb as his feet. Back and forth, back and forth. Where was it? Bad enough if

he

was unable to find it. Worse still if the snow held off until morning light and someone else did. Gods knew what it might say.

he

was unable to find it. Worse still if the snow held off until morning light and someone else did. Gods knew what it might say.

Dimly, he heard the Crier call one o' the clock. He was now covering ground he had already covered before, becoming more and more panicky.

Stop, Dennis. Stop, boy.

His da's voice, too clear in his head to be mistaken. Dennis had been on his hands and knees, his nose almost on the ground. Now he straightened up a little.

You're not SEEING anything anymore, boy. Stop and close your eyes for a moment. And when you open 'em, look around. Really look around.

Dennis closed his eyes tight and then opened them wide. This time, he looked around almost casually, scanning the whole snowy, tracked area around the foot of the Needle.

Nothing. Nothing atâ

Wait! There! Over there!

Something glimmered.

Dennis saw a curve of metal, barely poking half an inch out of the snow. Beside it, he could see a round track made by one of his kneesâhe had almost crawled over the thing during his frantic hunt.

He tried to pluck it from the snow and on his first try only pushed it farther in. His hand was almost too numb to close. Digging in the snow for the metal object, Dennis realized that if his knee had come down on it instead of beside it, he would have driven it more deeply into the snow without even feeling itâhis knees were as numb as the rest of him. And then he never would have seen it at all. It would have remained buried until the spring thaws.

He touched it, forced his fingers to close, and brought it out. He looked at it wonderingly. It was a tocketâa locket which might be gold, in the shape of a heart. There was a fine chain attached to it. The locket was shutâbut caught in its jaws was a folded piece of paper. Very old paper.

Dennis pulled the note free, closed his hand gently over the old paper, and slipped the locket's chain over his head. He got creakily to his feet and ran back toward the shadows. That run was, in a way, the worst part of the whole business for him. He had never felt so exposed in his whole life. For every step he ran, the comforting shadows of the buildings on the far side of the Plaza seemed to recede a step.

At last he reached comparative safety and stood in the shadows for a while, panting and shuddering. When he had gotten his breath, he returned to the castle, slinking along the Fourth Alley in the shadows and entering by Cook's Way. There was a Guard of the Watch at the doorway leading into the castle proper, but he was as sloppy about his duties as his mate had been the night before. Dennis waited, and eventually the guard wandered off. Dennis darted inside.

Twenty minutes later, he was safely back in the storeroom of the napkins. Here he unfolded the note and looked at it.

One side was closely writ in an archaic hand. The writer had used a strange rust-colored ink and Dennis could make nothing of it. He turned the note over and his eyes widened. He recognized the “ink” that had been used to write the short message on

this

side easily enough.

this

side easily enough.

“Oh, King Peter,” he moaned.

The message was smeared and blurryâthe “ink” had not been blottedâbut he could read it.

Meant to try Escape tonight. Will wait 1 night. Dare wait no longer. Don't go for Ben. No time. Too dangerous. I have a Rope. Thin. May break. Too short. Will be a drop in any case. 20 feet. Midnight tomorrow. Help me away if you can. Safe place. May be hurt. In the hands of the gods. I love you my good Dennis. King Peter.

Dennis read this note three times and then burst into tearsâtears of joy. That light Peyna had sensed was now shining brightly in Dennis's own heart. That was well, and soon all would be well.

His eyes returned again and again to the tine

I love you my good Dennis,

written in the King's own blood. He had not needed to add that for the message to make sense . . . and yet, he had.

I love you my good Dennis,

written in the King's own blood. He had not needed to add that for the message to make sense . . . and yet, he had.

Peter, I would die a thousand deaths for you,

Dennis thought. He put the note inside his jerkin, and lay down with the locket still around his neck. It was a very long time before sleep found him this time. And he had not slept long before he snapped wide awake. The door of the storeroom was openingâthe low creak of its hinges seemed an inhuman shriek to Dennis. Before his sleep-fuddled mind even had time to realize he had been found, a dark shadow with burning eyes swept down on him.

Dennis thought. He put the note inside his jerkin, and lay down with the locket still around his neck. It was a very long time before sleep found him this time. And he had not slept long before he snapped wide awake. The door of the storeroom was openingâthe low creak of its hinges seemed an inhuman shriek to Dennis. Before his sleep-fuddled mind even had time to realize he had been found, a dark shadow with burning eyes swept down on him.

103

T

he snow began at around three o' the clock that Monday morningâBen Staad saw the first flakes go skating past his eyes as he and Naomi stood at the edge of the King's Preserves, looking out toward the castle. Frisky sat on her haunches, panting. The humans were tired, and Frisky was tired as well, but she was eager to goâthe scent had grown steadily fresher.

he snow began at around three o' the clock that Monday morningâBen Staad saw the first flakes go skating past his eyes as he and Naomi stood at the edge of the King's Preserves, looking out toward the castle. Frisky sat on her haunches, panting. The humans were tired, and Frisky was tired as well, but she was eager to goâthe scent had grown steadily fresher.

She had led them easily from Peyna's farm to the deserted house where Dennis had spent some four days, eating raw potatoes and thinking sour thoughts about turnips which turned out to be as sour as the thoughts themselves. In that empty Inner Baronies farmstead, the bright-blue scent she had followed this far had been everywhereâshe had barked excitedly, running from room to room, nose down, tail wagging cheerfully.

“Look,” Naomi said. “Our Dennis burnt something here.” She was pointing at the fireplace.

Ben came and looked, but he could make out nothingâthere were only bundles of ash which fell apart when he poked at them. Of course, they were Dennis's early tries at his note.

“Now what?” Naomi asked. “He went to the castle from here, that's clear. The question is, do we follow or spend the night here?”

It had then been six o'clock. Outside it was already dark.

“I think we had better go on,” Ben said slowly. “After all, it was you who said we wanted Frisky's nose, not her eyes . . . and I, for one, would testify before the throne of any King in creation that Frisky has a noble nose.”

Frisky, sitting in the doorway, barked as if to say she knew it.

“All right,” Naomi said.

He looked at her closely. It had been a long run from the camp of the exiles, with little rest for either of them. He knew they should stay . . . but he was nearly frantic with urgency.

“Can you go on?” he asked. “Don't say you can if you can't, Naomi Reechul”

She put her hands on her hips and looked at him haughtily. “I could go on a hundred koner from the place where you dropped dead, Ben Staad.”

Ben grinned. “You may get your chance to prove it, too,” he said. “But first we'll have a bite to eat.”

They ate quickly. When the meal was finished, Naomi knelt by Frisky and quietly told her that she must take up the scent again. Frisky didn't have to be asked twice. The three of them quit the farmhouse, Ben with a large pack on his back, Naomi with one only slightly smaller.

To Frisky, Dennis's scent was a blue mark in the night, as bright as a wire glowing with an electric charge. She began to follow at once, and was confused when THE GIRL called her back. Then it came to her; if Frisky had been human, she would have slapped her forehead and groaned. In her impatience to be off, she had started sniffing up Dennis's backtrail. By midnight she would have had them back at Peyna's farmhouse.

“That's all right, Frisky,” Naomi said. “Take your time.”

“Sure,” Ben said. “Take a week or two, Frisky. Take a month, if you want.”

Naomi cast a sour glance Ben's way. Ben shut upâprudently, perhaps. The two of them watched Frisky nose back and forth, first across the dooryard of the deserted farm, then across the road.

Other books

Islam and Democracy: Fear of the Modern World by Fatima Mernissi, Mary Jo Lakeland

Serpent on the Rock by Kurt Eichenwald

Los ingenieros de Mundo Anillo by Larry Niven

Crown of Renewal (Legend of Paksenarrion) by Moon, Elizabeth

50 Harbor Street by Debbie Macomber

Ask the Dark by Henry Turner

A Loving Spirit by Amanda McCabe

Against Her Will (Dragon's Lair) by Britta Ashley

Bygones by Kim Vogel Sawyer

Leah's Choice by Marta Perry