The Flamingo’s Smile (7 page)

Read The Flamingo’s Smile Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

LA GRANDE GALERIE

of the Muséum d’histoire naturelle in Paris has been closed for fifteen years. This great space, supported by iron and roofed in glass, is no longer structurally sound. Like the capacious nineteenth-century railroad stations that served as its model, La Grande Galerie has passed into history. Its exhibits, too, reflect the thoughts and concerns of another age, the expansive and aggressive Victorian era that took so seriously, as a guide for collection and display, the words of Genesis (1:22): “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas, and let fowl multiply in the earth.” If modern museums emphasize intimacy, good lighting, tasteful display, and well-chosen words, their Victorian predecessors judged quality by quantity and crammed as many large animals as possible into their vast open spaces. At Lord Rothschild’s museum in Tring, the stuffed zebras are supine, so that several tiers may be fitted from floor to ceiling.

La Grande Galerie is the granddaddy of this superseded style. Built in 1889, and unchanged since, its skeletons and stuffed animals occupy every available inch. The great central pyramid almost reaches the high glass ceiling. One side is all zebras, another all antelopes; six giraffes crown the summit. The dust is thick, the hall dark and empty; eerie silence marks a dingy majesty.

The companion hall, La galerie d’anatomie comparée, is smaller, well lit, and still open. Its style is identical—row upon endless row, tier upon tier of blanched skeletons. I wandered up and down the aisles, marveling at a long row of walruses and five superposed tiers of monkey skulls. Then I passed by cabinet 106 and stopped short. It contains a sideshow to offset the neighboring forest of sleek lions, and to remind complacent Victorians that nature can be capricious and cruel, as well as bountiful. Cabinet 106 holds a collection of teratological specimens, skeletons of deformed and abnormal births. Most are human and most represent that puzzling and frightening phenomenon of joined birth, or “Siamese” twinning. Skeleton A8597 has two heads, three arms, and two legs; A8613 has four arms, two legs, and two heads projecting from the ends of a joined vertebral column; A8572 is almost normal, but a tiny, headless brother with arms and legs projects from his chest. All are small and clearly died at birth or soon thereafter.

One skeleton stands out for its considerably larger size. A8599 is (or are)—and this is the issue we shall soon discuss—twin girls with two well-formed heads and upper bodies with four full arms. Two distinct vertebral columns nearly join at their base, and only two well-formed legs extend below. The label reads

monstre humain dicéphale

, or “two-headed human monster.” But A8599 was born live and survived several months. The twins were baptized and given names. The label records this poignant detail and includes, under the number and description, the simple identification “Ritta-Christina.”

I mused much over Ritta and Christina, wondering about their life and death. Yet I would not have made the transition from troubled thought to essay had I not discovered, quite by accident, a dusty old tome in a bookstore two days later—volume 11, for 1833, of the

Memoirs of the Royal Academy of Sciences

. It contained a long monograph by the great medical anatomist Etienne Serres:

Théorie des formations et des déformations organiques, appliquée à l’anatomie de Ritta Christina, et de la duplicité monstrueuse

(“Theory of organic development and deformation, applied to the anatomy of Ritta Christina, and to duplicate monsters in general”).

Anyone who does not grasp the close juxtaposition of the vulgar and the scholarly has either too refined or too compartmentalized a view of life. Abstract and visceral fascination are equally valid and not so far apart. Two days before, I had seen young schoolchildren standing before Ritta-Christina in open-mouthed awe or horror, soon masked by forced humor. Now I learned that France’s finest medical anatomist had dissected Ritta-Christina and used her to support a general theory of organic (not only human) embryology. Both themes seemed equally compelling to me; indeed, I had wallowed in both myself for two days. The children might not have generalized, but I have no doubt that M. Serres once gulped, as well as thought. I bought the book.

Ritta and Christina were born on March 23, 1829, to poor parents in Sardinia. Times were hard and social mobility scarcely possible in ordinary circumstances. Parents today would receive pity and experience only sorrow; in 1829, realistic people, whatever their private feelings, must have recognized that such a child represented potential and substantial revenue, otherwise quite unobtainable.

*

Thus, the parents of Ritta-Christina scraped together some funds and brought her to Paris, hoping to display her at fancy prices. The Hottentot Venus had provoked enough protest fifteen years earlier (see essay 19); but she was whole, however exotic. Public sensibilities had limits, and the authorities forbade any open display of Ritta and Christina. But she was shown privately, many times too often—for she died, in part from overexposure, after five months of life.

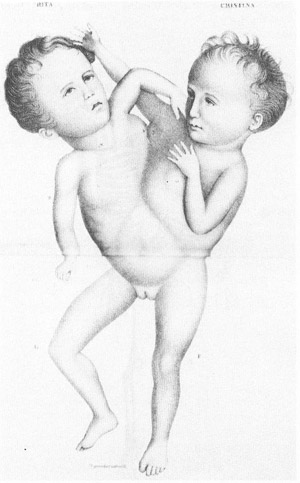

Ritta-Christina, drawn from life.

FROM SERRES

, 1833.

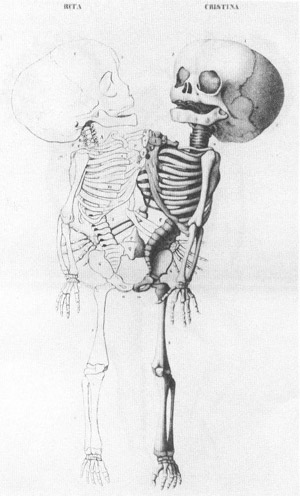

The skeleton of Ritta-Christina after Serres’s preparation and still on display in Paris.

FROM SERRES

, 1833.

I have consciously switched back and forth from singular to plural in describing Ritta-Christina. When the vulgar and scholarly meet, a common question often underlies our joint fascination. One question has always predominated in this case—individuality. Was Ritta-Christina one person or two? This issue inspired the feeble jokes of my terrified schoolchildren. It also motivated Serres’s scientific investigation. The same question underlay public fascination in 1829. When Ritta-Christina died, a Parisian newspaper wrote: “Already it is a matter of grave consideration with the spiritualists, whether they had two souls or one.”

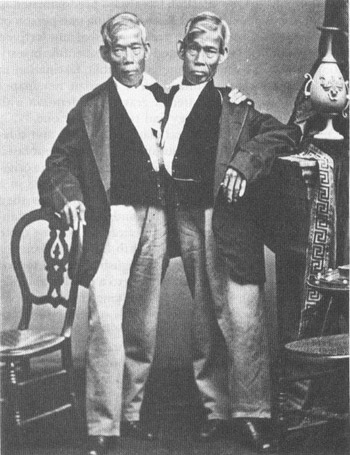

One or two? Through all scholarly excursions and sideshow huckstering, this single question has focused our fascination since Siamese twinning received its name. The originals, Eng and Chang, were born of Chinese parents in a small village near Bangkok in 1811 (Thailand was then called Siam). During the late 1820s and 1830s, they exhibited themselves in Europe and America and became quite wealthy. They decided to live in North Carolina where, at age 44, they married two sisters of English birth and settled down in two neighboring households to a comfortable life as successful (and, yes, even slaveholding) farmers. They switched houses at three-day intervals, traveling the one-and-a-half-mile distance by carriage. By the customs of the day, Chang was unquestioned master in his domicile, while Eng gave the orders

chez lui

. The unions were undeniably productive, for Chang had 10 children and Eng 12.

Chang and Eng were physically complete human beings connected by a thin band of tissue, three and a quarter inches at its widest and only one and five-eighths inches at its thickest. Each had a full set of parts down to the last toenail. They carried on independent conversations with visitors and had distinct personalities. Chang was moody and melancholy and finally took to drink; Eng was quiet, contemplative, and more cheerful. Yet even they, history’s most independent Siamese twins, apparently harbored private doubts about their individuality. They signed all legal documents “Chang Eng” and often spoke about their ambiguous feelings of autonomy.

Eng and Chang, the original Siamese twins.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE GRANGER COLLECTION

.

But what of Ritta and Christina, whose bodily independence did not extend below the navel? They seemed, at first glance, to be two people above and only one below. The old cultural criterion of head and brain might have suggested an easy resolution—two heads, two people. But as a scientist, Serres resisted this facile answer, for he had also studied Siamese twins with one head, two arms, and four legs. He reasoned that a uniformity of process must underlie both types of twinning and could not accept the simplistic resolution—one person if zipped halfway but starting from the top; two if zipped from the bottom.

Serres struggled with this momentous issue for 300 pages and finally concluded that Ritta

and

Christina were two people. His arguments and basic style of science belong to another era in the history of biology. They are worth recounting if only because few intellectual exercises can be more rewarding than an examination of how radically different systems of thought treat a common subject of mutual interest. I also believe that Serres was at least half wrong.

Serres represented the great early nineteenth-century tradition of romantic biology, called

Naturphilosophie

(“nature philosophy”) in Germany and transcendental morphology in his native France. If modern morphologists study form either to determine evolutionary relationships or to discover adaptive significance by examining function and behavior, Serres and his colleagues pursued markedly different goals. They were obsessed with the idea that some overarching, transcendental law must underlie and regulate all the apparent diversity of life.

These laws, in the Platonic tradition, must exist before any organism arises to obey their regularities. Organisms are accidental incarnations of the moment; the simple, regulating laws reflect timeless principles of universal order. Biology, as its primary task, must search for underlying patterns amidst the confusing diversity of life. In short, biologists must seek the “laws of form.”

Serres contributed to the transcendental tradition by extending its concerns to embryology. Most of his colleagues had emphasized the static form of adults by searching for underlying patterns in final products alone. But organisms grow their own complexity from egg to adult. If laws of form regulate morphology, then we must discover principles for dynamic construction, not merely for relationships among finished creatures.

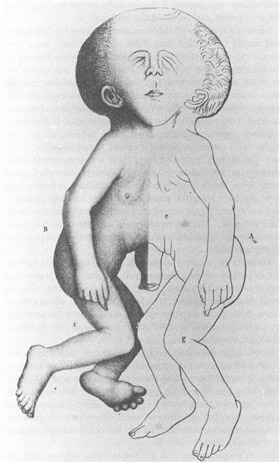

A Siamese twin pair of conformation opposite to Ritta-Christina: one upper and two lower bodies.

FROM SERRES

, 1833.

Serres’s monograph on Ritta-Christina begins with an abstruse 200-page dissertation on the principles of morphology and their application to embryology. Unless we sneak a peek at the alluring plates in the back (including the three figures reproduced with this essay), we hear nothing of the famous Sardinian twins until our senses are numbed by generality. This organization, in itself, reflects a style of science strikingly different from our own. We maintain an empirical perspective and like to argue that generalities arise from the careful study and collation of particulars. Any modern embryologist would discuss Ritta-Christina first and only venture some short and cautious conclusions at the end. But Serres, as a transcendentalist, believed that laws of form existed before the animals that obeyed them. If abstraction preceded actuality in nature, why not in human creativity as well? Thought and theory first, application later. (Neither extreme well represents the intricate interplay of fact and theory that regulates our actual practice of science. Still, I suspect that Serres’s “inverted” order is no worse a distortion of complex reality than our modern stylistic preferences.)