Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

The Food of a Younger Land (21 page)

Moonstone glances in the direction of Doak. “I knows of some folks what would eat ’em any way a’tall, jes like they come from the hawg, even.”

This brings a round of uproarious laughter that drowns out Doak’s reply.

Aunt Orianna has remained silent during this argument, scratching the wart on her ear meditatively. Now the old woman takes a dip of snuff, and peeping over the brass-rimmed glasses set aslant her flat nose, she speaks in a thin treble voice: “When I come in the do, I didn’t smell no collards cookin, nor turnips neither. ’Course,” she glances at Mehitable politely, then grins at the empty plate on her knee, “Mehitable’s chitlins is purest and best of any in this whole Cape Fear country. They is most tasty as possum gravy.”

Truletta Spoon, belle of chitlin struts for the past two seasons back, sits beside Aunt Orianna. Truletta is wearing a bright yellow cotton dress, which goes well with her russet skin. A wide red belt encircles her slim waist. Red slippers are dyed with “sto-bought” colors.

“My Granny say chitlin dinner sets better iffen a mess of collards and green vinegar pepper goes long with. I likes mine seasoned with red pepper. I have eat sweet taters and biscuit served at strut suppers, but my fambly likes to refresh our hawg meat with corn pone.”

“Does you cut yo chitlins afore they is cooked, Auntie?” Mehitable asks respectfully, “or does you cook ’em afore you cuts ’em?”

“I cooks ’em whole, honey, and cuts ’em after. After we takes the intrils from the hawg, I rids

a

’em and empties the waste in a big ol hole dug in my yawd. I gits back to where there is water aplenty, and I fills them chitlins full, and rinses ’em up and down, up and down.” Aunt Orianna motions with her skinny arms, and makes a sucking noise with her lips to imitate the water washing through.

a

’em and empties the waste in a big ol hole dug in my yawd. I gits back to where there is water aplenty, and I fills them chitlins full, and rinses ’em up and down, up and down.” Aunt Orianna motions with her skinny arms, and makes a sucking noise with her lips to imitate the water washing through.

“My Granny soaks ’em in clean cold water without salt not less than four to six hour, then she soak ’em in salt water from twelve to fourteen hour. My Granny turn her chitlins on a switch.

b

”

b

”

Truletta shuffles her feet self-consciously. “I knows hawgs is moon-killed.”

“Everybody know that, honey. Hawg meat aint fitten to eat if it aint killed either three days afore or after moon turns. Grease will all fry out iffen you kills a hawg on too ol a moon. Same’s a body must mind not to pity no hawg at butcherin, lessen it die hard.”

The women remove the table cloths and the men pitch in, moving chairs back against the walls and taking down the tables, which are carried outside the cabin. While the house is cleared for the dancing, jugs of cider are brought out and guests are served from tin cups.

The banjo boys are tuning up, taking much time in the process, while the guests fret for the fun to begin.

After a few preliminary flourishes the musicians swing into the rapid tempo of “Left Footed Shoo Round.” The strut is on.

Hands clap softly, and bodies sway back and forth with the music. Men move toward the women, inviting partners. The leader, standing by the banjo boys, calls out in a sing-song tenor:

“Ketch you partner by the arm,

Swing her round, ’twont do no harm.”

Into the center of the floor jumps Carter Dunlap, a town Negro who never misses a strut. Dunlap is dressed in a tightly fitting suit of black and grey checks, padded substantially at the shoulders. His light tan shoes are well polished. Shirt and tie are checked, but of lighter tones than the suit.

With a glass of cider in each hand, and a third balanced on the top of his head, Carter begins shifting his feet on the floor. At first the tan shoes move but slightly. Then, as the banjoists swing into “Guinea Walk” Carter moves with more energy. He slides one foot forward and draws up with the other. Round he spins, faster and faster, now squatting, now leaping toward the rafters. Sometimes the glass on his head teeters precariously, but he finishes up without spilling a drop, a feat that draws a round of noisy applause.

Moonstone Peeley gives a demonstration of “cutting the buck,” then turning, he takes Truletta Spoon in his arms and swings her dizzily in the middle of the room. Couples vie with each other in cutting didos. Some of the men lift their partners off their feet and whirl them rapidly around.

On goes the dance, the banjos strumming faster and faster. The hearth fires blaze brightly, and soon the dancers are perspiring freely. Men take off their coats and throw them over chairs. Sweat flows from cheek and jowl; shirts become wet through. The women mop their faces with damp handkerchiefs. The floor boards creak, the lanterns bob up and down. More tunes and more dances until past midnight, when the strut breaks up.

Mehitable and Doak stand at the door, bidding their guests good-night.

“She glad everthing went off good and social and no trouble.”

“No use fightin like they done over to Uless Sherman’s. Reckon Uless ever goin to get outten the jailhouse?”

“Was sure a tasty feast, sister. Must have took a lot of cawn to fatten yall’s pig-tail.”

“Glad it set well. See you at meetin.”

The slim crescent moon rides high behind the slender trunks of spindly pines. Bare gourd-vines on the cabin porch are dimly etched in the pale light. Across the river a hound bays. Mehitable and Doak turn to enter the cabin.

“Les let the dishes res till mornin come,” sighs Mehitable.

Menu for Chitterling Strut

(A North Carolina Negro Celebration)

25¢

Chitterlings

—Cold boiled with vinegar and red pepper sauce.

Hot boiled with barbecue dressing.

Fried crisp and brown.

Cold slaw.

Cucumber pickle, sweet or sour.

Hot corn pone and butter.

Sweet potato custard.

Hard cider.

—Cold boiled with vinegar and red pepper sauce.

Hot boiled with barbecue dressing.

Fried crisp and brown.

Cold slaw.

Cucumber pickle, sweet or sour.

Hot corn pone and butter.

Sweet potato custard.

Hard cider.

15¢

Chitterlings

—Served any way.

Pickle.

Corn pone.

Cider.

—Served any way.

Pickle.

Corn pone.

Cider.

T

hese struts are held in the homes of the Negro for the purpose of making money to be used for anything from paying church to buying a winter coat. The meal is served on a long table reaching across the room. Wash tubs of cider sit on each end of the table where it is served with tin dippers. The pickle, slaw and potato custards are placed at intervals along the white cloth, but the chitterlings and corn pone are served hot from the kitchen.

hese struts are held in the homes of the Negro for the purpose of making money to be used for anything from paying church to buying a winter coat. The meal is served on a long table reaching across the room. Wash tubs of cider sit on each end of the table where it is served with tin dippers. The pickle, slaw and potato custards are placed at intervals along the white cloth, but the chitterlings and corn pone are served hot from the kitchen.

The Negroes begin to gather by sundown. The host walks around barking:

“Good fried hot chitlins crisp and brown,

Ripe hard cider to wash dem down,

Cold slaw, cold pickle, sweet tater pie,

And hot corn pone to slap your eye.”

Ripe hard cider to wash dem down,

Cold slaw, cold pickle, sweet tater pie,

And hot corn pone to slap your eye.”

By nine o’clock the feed is over and the shoo round strut begins. The table is pushed aside. The banjo pickers take their places back under the stair steps out of the way. With the first clear notes a high brown leaps to the center of the floor and cuts the buck. Couples form, then comes the steady shuffle of feet and the strut is on.

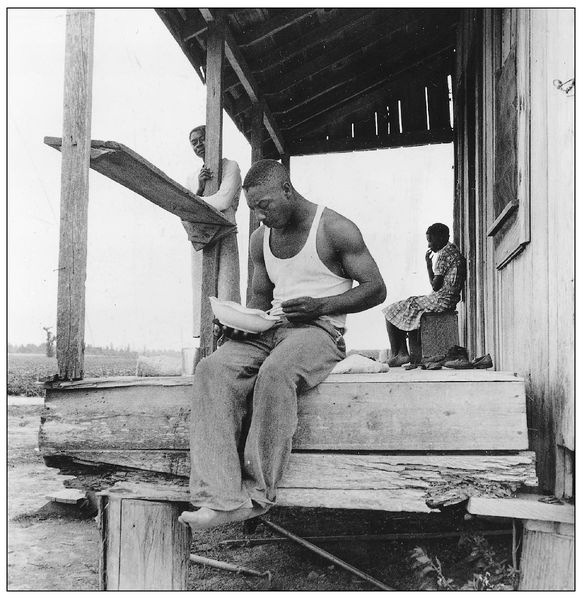

SHARECROPPER EATING NEAR CLARKSDALE, MISSISSIPPI. (PHOTOGRAPH BY DOROTHEA LANGE )

Mississippi Chitlins

I

t has been said that hog meat, in one form or another, is the Mississippian’s staple diet. And considering how we eat it fresh in winter, cured in spring, and salted in summer, and how we use the belly fat with vegetables the year round, we have to admit that pork is certainly our dish. It is all good eating, from the hog jowls to the squeal, but come a cold January day and hog-killing time, what we hanker after is the chitlins.

t has been said that hog meat, in one form or another, is the Mississippian’s staple diet. And considering how we eat it fresh in winter, cured in spring, and salted in summer, and how we use the belly fat with vegetables the year round, we have to admit that pork is certainly our dish. It is all good eating, from the hog jowls to the squeal, but come a cold January day and hog-killing time, what we hanker after is the chitlins.

We favor the small intestines for our chitlin feast but the small ones come in right handy for casing the sausage meat, so the large intestines will do. It takes a keen knife to split the intestines from end to end, then they must be scraped and washed until they are good and white. They have to soak overnight in salted water but since we, ourselves, are too tired from hog sticking to do the dish justice, we can wait.

By sun-up Ma has drained the chitlins and put them to boil in fresh salted water. She does this outdoors since boiling chitlins have a right high stench and she won’t have them smelling up her kitchen. After they boil tender, Ma takes them out and cuts them into pieces two or three inches long. She says you can meal them or flour them according to your fancy, but she always meals hers and fries them crisp in deep fat. Those that like ’em extra hot put red pepper and sage in the boiling water, and everybody sees that there’s plenty of catsup and salt and pepper on the table.

There is a state organization which calls itself the Mississippi Chitlin Association. Mr. Dan B. Taylor is president and Mr. Pat V. James, of Hot Coffee, is secretary. Mr. Si Corley, State Commissioner of Agriculture and an enthusiastic member, says that the sole object of the meeting is chitlin eating and that the members waste no time getting down to the business at hand.

Kentucky Oysters

This was an interview by the Kentucky Writers’ Project with G. R. Mayfield and his wife, whose name was not given. They had worked as cooks in a number of prominent Louisville restaurants for forty years, and at the time they were interviewed for

America Eats

they were retired. Notice the delicacy with which the cut of meat in question is never identified by name.

America Eats

they were retired. Notice the delicacy with which the cut of meat in question is never identified by name.

N

egroes of Kentucky look forward to the fall of the year for their annual treat, “Kentucky Oysters.” Every fall, just after the first frost, comes “hog killin’,” a time when hogs on the farm are slaughtered for winter use. “Kentucky Oysters” are the porcine equivalent of lamb fries. Placed in cans for commercial use, this part of the hog is in season according to the same tradition as the salt water bivalve from which it gets its name. It is in season during all the calendar months with an “R” in the spelling.

egroes of Kentucky look forward to the fall of the year for their annual treat, “Kentucky Oysters.” Every fall, just after the first frost, comes “hog killin’,” a time when hogs on the farm are slaughtered for winter use. “Kentucky Oysters” are the porcine equivalent of lamb fries. Placed in cans for commercial use, this part of the hog is in season according to the same tradition as the salt water bivalve from which it gets its name. It is in season during all the calendar months with an “R” in the spelling.

G. R. Mayfield, long famous in Louisville as head cook at the old Willard Hotel (22 years), the Louisville Old Inn (4 years), Fontaine Ferry Park (5 years), and for the past decade, until his recent retirement, at the Municipal Airport at Bowman Field, where he prepared the meals for the airline passengers to be picked up here, has prepared hundreds of Kentucky oysters for both the Negro and white trade.

He said recently: “Yes, manys a time I’ve cooked ’em. There’s two ways of cooking ’em. Some folks jist like ’em boiled in two waters, pouring the first water when they are about cooked and then using a second water to make ’em tender. Others like ’em parboiled, then wrapped in a batter of raw eggs with plenty bread crumbs and fried in deep fat. Course if you can get it, rich bacon grease is the best. Either way you cook ’em they is served with cabbage slaw and corndodgers or corn bread.”

Another delicacy high in the esteem of Negroes in Kentucky is roast possum, which grows scarcer every year. According to Mr. Mayfield, the preparation of this dish is simple. The possum is roasted as a young pig is roasted, garnished with sweet potatoes. If dressing is desired it is prepared and cooked separately. But as Mr. Mayfield explained, the only trouble with this dish is “You’all got to cotch your pussum first.”

Louisiana “Tête de Veau”

H. MICHINARD

H. Michinard wrote a great deal about New Orleans, including reminiscences of Creole life in New Orleans, and worked under Lyle Saxon for the Louisiana Writers’ Project on “Negro Narratives” and many other FWP projects.

I

remember when a child, my grandfather was reputed as having the best table in town and of being a “fin gourmet.” He prided himself of buying all the choicest things on the market; he believed also in variety, so there was always something new on the menu. One of the many things he was fond of, also my uncles (six of them), was a “Tête de Veau” (calf’s head) a la _______ .

remember when a child, my grandfather was reputed as having the best table in town and of being a “fin gourmet.” He prided himself of buying all the choicest things on the market; he believed also in variety, so there was always something new on the menu. One of the many things he was fond of, also my uncles (six of them), was a “Tête de Veau” (calf’s head) a la _______ .

We children refused flatly to partake of that dish, and I invariably made a grimace when grandfather began carving the ears and digging out the eyes, which it appears were the choicest morsels. There was a fight over who would have one of the eyes.

The children had great fun after there was only a carcass left to pull out one by one the remaining teeth, some of them having been lost during the process of boiling.

There is a saying that, “C’est la sauce qui fait le poisson,” well to me it was the French dressing that gave rest to the calf’s head.

Kentucky Wilted Lettuce

T

hroughout Kentucky, and particularly in the mountainous area, wilted lettuce is certain to appear on the table of most every household that has a garden. Fresh leaf lettuce is washed, cut crosswise in one-half inch strips and placed in the bowl from which it is to be served. Fresh green onions are cut over the top with sufficient salt and pepper. Hot bacon grease, containing small crisp pieces of bacon, is poured over the lettuce. After it has produced its wilting effect vinegar, diluted with water to the desired strength, is added.

hroughout Kentucky, and particularly in the mountainous area, wilted lettuce is certain to appear on the table of most every household that has a garden. Fresh leaf lettuce is washed, cut crosswise in one-half inch strips and placed in the bowl from which it is to be served. Fresh green onions are cut over the top with sufficient salt and pepper. Hot bacon grease, containing small crisp pieces of bacon, is poured over the lettuce. After it has produced its wilting effect vinegar, diluted with water to the desired strength, is added.

Other books

Public Display of Affection by Emily Cale

Off Sides by Sawyer Bennett

Love at Second Sight by Cathy Hopkins

World Enough and Time by Nicholas Murray

Asesinato en el Comité Central by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán

Muerte y vida de Bobby Z by Don Winslow

Craving Temptation by Deborah Fletcher Mello

REMEDY: A Mafia Romance (Return to Us Trilogy Book 3) by M.K. Gilher

Cat Class (Trick Or Treat) by Slayer, Megan

What an Earl Wants by Kasey Michaels