Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

The Food of a Younger Land (38 page)

Liberty Orchards Company

Cashmere, Washington

Cashmere, Washington

December 13, 1941

Mr. Glenn H. Lathrop,

State Supervisor,

Washington Historical Records Survey,

Work Projects Administration,

819 Western Avenue,

Seattle, Washington

Mr. Glenn H. Lathrop,

State Supervisor,

Washington Historical Records Survey,

Work Projects Administration,

819 Western Avenue,

Seattle, Washington

Dear Sir:

We are in receipt of a letter from Viola Lawton, Area Supervisor of District No. 1, in Spokane, requesting that we furnish your office with data on Aplets, as a food product peculiar to our state. Not knowing just what type of data you desire makes it rather difficult for us to determine just what to give you in this letter.

Aplets were first put on the market in late 1919 and early 1920, by two naturalized citizens of Armenian parentage, Mr. M. S. Balaban and Mr. A. L. Tertsagian, brothers- in- law, who for a few years previous to that time had been putting out evaporated apples in a small plant located in Cashmere, Washington. When the new confection caught the public fancy, this evaporating business was discontinued and the factory given over to the manufacture of the candy alone. In 1923, a larger and more convenient factory was built adjoining the old frame building in which the industry was started. This new factory was damaged by fire in 1928, and rebuilt after the fire, with an office addition built on at that time.

Aplets are based on apple juice extracted from the lower grades of the fruit grown so abundantly in the Wenatchee Valley, sugar, the finest quality of California and Oregon walnut meats, and other ingredients of correspondingly high grade. In 1932 another fruit-nut confection, called Cotlets, because it contains sun-dried apricots, and apricot pulp, was added to the line, and is also becoming most popular with the buying public. Both products meet the high quality demanded by the Pure Food and Drug Act, and are healthful, satisfying sweets for all ages and classes.

We trust this is the information desired, and are

Very truly yours,

Liberty Orchards Co.,

By: Blanche Wood

By: Blanche Wood

“The Unique Fruit-Nut Confections of the Golden West”

Colorado Superstitions

E

very state has numerous folklore traditions that have been handed down from generation to generation. Colorado is no exception. Many of these traditions and superstitions were brought here by our pioneer ancestors and probably were products of another environment. Among the more commonly known superstitions are these:

very state has numerous folklore traditions that have been handed down from generation to generation. Colorado is no exception. Many of these traditions and superstitions were brought here by our pioneer ancestors and probably were products of another environment. Among the more commonly known superstitions are these:

1. If apple butter is made in the dark of the moon, it will not splash in cooking.

2. In stirring butter or in churning butter, the motions must be sun-wise. Reversing the direction will invite bad luck.

3. Do not burn bread crust in the kitchen fire, or bad luck will come to that household.

4. In killing meat of any kind, it should be done near the full of the moon, and the meat will not shrink up when cooked.

5. Always make vinegar in the full of the moon.

6. Make sauerkraut in the sign of the feet, and it will always cook tender and remain sweet.

7. Set the home so that the chickens come out in the full of the moon.

8. Potatoes planted in the “light” of the moon run to stalk. Those placed in the “dark” of the moon will make better potatoes.

9. A Ute Indian superstition is: “Plant all root plants, like beets, potatoes, onions in the dark of the moon, and all plants like spinach, lettuce and corn in the light of the moon. If you plant these vegetables in the light of the moon, they will be all tops.

10. In moving to another house, take a loaf of bread and a small bag of salt to the house first; hide these articles somewhere in the house. Privation and want will never enter that house.

11. Vegetables or fruit that produce above the ground should be planted on the increase of the moon. Roots and vegetables that produce in the earth should be planted on the decrease of the new moon.

12. You will receive mail from the direction in which your pie is pointing, when it is set down at your place at the table.

13. A piece of pie set with the point toward you meant a letter; with point to one side, a package; if directly away from you, it means nothing.

14. If a piece of silver falls to the floor from the dining table, it means that someone is coming hungry.

15. A long thin tea-leaf in a cup of tea means a stranger is coming to see you. If you put it on the back of your hand and stamp it with your other fist for each day of the week, you can tell when he is coming (by the day at which the leaf adheres to the fist).

16. Salt spilled toward a person is a lucky omen.

17. Thirteen guests at a dinner-table means a betrayal.

18. If you spill something on the stove, put salt on it to keep from having a fuss.

19. Cook black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day and you will be blessed with plenty all the year.

20. If you put a piece of wedding-cake under your pillow for seven successive nights, on the seventh you will dream of your future husband.

21. If a dandelion (or buttercup) placed under your chin throws a yellow light, you “love butter.”

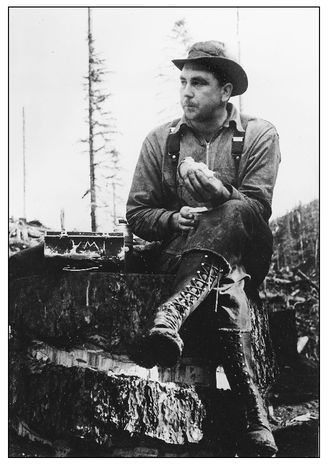

LUMBER JACK EATS LUNCH, LONG BELL LUMBER COMPANY, COWLITZ COUNTY, WASHINGTON. (PHOTO - GRAPH BY RUSSELL LEE)

Washington State Hot School Lunches

P

rior to 1936, in Snohomish County and rural districts of other counties in the Puget Sound Northwest, there was no original plan for “Hot Lunches” for school children. During the early depression period, 1929-36, many plans were tried at the various schools for supplying additional food to undernourished children.

rior to 1936, in Snohomish County and rural districts of other counties in the Puget Sound Northwest, there was no original plan for “Hot Lunches” for school children. During the early depression period, 1929-36, many plans were tried at the various schools for supplying additional food to undernourished children.

In School District #6, Snohomish County (Mukilteo), the custom was instituted in 1930 of having the families take turns in supplying a hot dish for the entire school. The Parent Teachers Association purchased kettles and small electric hot plates to be used for the school lunch purpose and the hot dish generally consisted of one of the following: boiled beans, macaroni and cheese, spaghetti and tomatoes, various kinds of soups, or hot cocoa. No attempt was made at a balanced diet, the main object being to supply undernourished children with at least one hot dish per day.

Families living close to the school building delivered the dish hot at noon time, while those living further away sent the prepared food on the school bus and it was warmed up on the school hot plates by the teacher at lunch time.

This system was adopted by other school districts with variations in manner of handling. At Silver Lake, in 1932, the hot dish was prepared by volunteers of the Unemployed Citizens League, who also solicited foods to be used and served to the children without charge. In other districts the program was sponsored by community clubs, granges, and unemployed groups.

The School Lunch Program, under the Works Progress Administration since 1936, has grown from a few school districts cooperating until in October 1941, 32 separate school lunch projects were operating in second and third class districts throughout Snohomish County, serving an average of 4,112 hot lunches daily at an average cost of 2¢ per lunch. The cooks and helpers are supplied by the Work Projects Administration [the WPA name changed to Work Projects Administration in 1939] and a certain amount of food is supplied by the Surplus Commodities; all other finances are taken care of by the district sponsoring the program, either by per dish charge, weekly or monthly contributions by parents, or donations of foods.

The Basques of the Boise Valley

RAYMOND THOMPSON

The Basques, the oldest European culture, a people who live in a small coastal region of the western Pyrenees between France and Spain, speak an ancient language unrelated to any other known tongue, and have long been at the vortex of whirling controversies over linguistics, anthropology, and politics. But they are largely known in the American West as shepherds or, as they say in the West, sheepherders.

The American West—eastern California, Oregon, Washington, Southern Idaho, and Nevada—has suffered a shortage of sheepherders since the mid-nineteenth century. Sheep will graze and flourish in land too rugged for cattle. But sheep are much more work than cattle because they must be moved from one slope to another to find food. It was and still is a hard and lonely job, working long hours alone in the mountains, living in a crude trailer with only hard-working sheep dogs for companions.

At first the owners recruited Scots for the work, but by the late nineteenth century through to the time of

America Eats

they recruited Basques who had grown up on farms where they looked after a few sheep. Many such farms were on the French side, which is not losing its Basque character as the following article suggested, but more were from the Spanish side. It is also not true, as this Idaho Writers’ Project article suggests, that they came to the United States because they were from an ancient line of shepherds. There were few full-time shepherds in the Basque provinces. The recruits were simply farm people in need of work. Nor is it true, as Thompson states, that they were drawn to the West because it resembled their native land. Basque land—with its velvet green slopes on mountains on the scale of the Adirondacks, though more rugged, and never far from the Atlantic Ocean, a central part of Basque history—is very different from the giant, arid landscape of the landlocked Rocky Mountains.

America Eats

they recruited Basques who had grown up on farms where they looked after a few sheep. Many such farms were on the French side, which is not losing its Basque character as the following article suggested, but more were from the Spanish side. It is also not true, as this Idaho Writers’ Project article suggests, that they came to the United States because they were from an ancient line of shepherds. There were few full-time shepherds in the Basque provinces. The recruits were simply farm people in need of work. Nor is it true, as Thompson states, that they were drawn to the West because it resembled their native land. Basque land—with its velvet green slopes on mountains on the scale of the Adirondacks, though more rugged, and never far from the Atlantic Ocean, a central part of Basque history—is very different from the giant, arid landscape of the landlocked Rocky Mountains.

At home their family may have owned a few sheep or even a large flock of several hundred. But in the American West they were left in charge of many thousands of valuable sheep. A flock could be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Today a single sheep is worth about one hundred dollars. A sheepherder had to be both skilled and responsible. The western range, unlike their native European farms, included thousands of miles. Some Basques did not know exactly what they were doing. One Basque, who said he came because he didn’t like the jobs he was finding at home, said, “The only thing I knew about sheep was that they know where they are going. So I followed them.”

The Basques, both in their native Europe and in the West, are widely appreciated for their food and cooking ability. Some of the dishes mentioned here are typically Basque, but many are Spanish. The anisette mentioned is not at all a Basque drink.

The Basque tendency to assimilate in Idaho seems true because today, while they still maintain traditional festivals with Basque music and dance and an entire block of downtown Boise is devoted to Basque culture, few Idaho Basques speak the ancient language. The second, third, and fourth generations are not shepherds but doctors, lawyers, bankers, politicians, building contractors, and, of course, a few restaurateurs. And while they are still appreciated for their culinary abilities, Idaho Basques have evolved their own cuisine, which seldom includes the salt cod, baby eels, or other seafood that typifies Basque cuisine. Instead it is a cuisine largely based on lamb. While lamb is part of the Basque tradition, nowhere is it as central as it is to today’s Idaho Basques. This in turn is a little surprising because in general Americans now eat far less lamb than in the days of

America Eats.

At the time of

America Eats

there were literally more sheep than people in Idaho, but today the sheep population is about one tenth of its pre- World War II population. Before the war so much lamb and mutton was produced in the West that the U.S. Army bought massive amounts, especially of mutton, and froze it, producing such awful meals for World War II G.I.s that many came home vowing never to eat lamb again. The market for lamb rapidly declined after the war, except in New York City, which has always been known for its love of lamb. After the war New York consumed more than half the lamb eaten in America.

America Eats.

At the time of

America Eats

there were literally more sheep than people in Idaho, but today the sheep population is about one tenth of its pre- World War II population. Before the war so much lamb and mutton was produced in the West that the U.S. Army bought massive amounts, especially of mutton, and froze it, producing such awful meals for World War II G.I.s that many came home vowing never to eat lamb again. The market for lamb rapidly declined after the war, except in New York City, which has always been known for its love of lamb. After the war New York consumed more than half the lamb eaten in America.

With Basques too affluent in Europe to emigrate and herd sheep, today the Western sheep owners represented by the Western Range Association recruit Peruvians and a few Mexicans and an occasional Mongolian. They are allowed to bring these people in, as they were the Basques and Scots before them, because of the claim that there is no one in America willing and qualified to do the job. To prove the claim the Western Range Association periodically runs ads looking for American shepherds, but no qualified applicants ever turn up.

Other books

Candied Crime by Dorte Hummelshoj Jakobsen

Darius & Twig by Walter Dean Myers

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Tyger by Julian Stockwin

Exposed: Misbehaving with the Magnate by Kelly Hunter

Doctor Who: The Mark of the Rani by Pip Baker, Jane Baker

Mountain Sanctuary by Lenora Worth

Absolutely Normal Chaos by Sharon Creech

Gold Comes in Bricks by A. A. Fair (Erle Stanley Gardner)