The Food of a Younger Land (47 page)

Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

The dish—at first a general preparation designed to use appetizingly the best parts of a freshly killed calf—developed specialists with varying recipes. Aging men with slightly bowed legs and handle-bar mustaches still argue, and will until they die, as to the relative merits of what these super-cooks worked out. John Snyder, of Amarillo in the Texas Panhandle, who is nationally famous as a barbecue artist, is also held in high esteem for his son-of-a-gun, and this is his recipe:

“You kill and dress the fattest calf that can be found. Then you take parts of the liver, heart, sweetbreads, narrowgut, tongue, and some of the tenderloin, and choice bits of flank steak. You start the cooking by putting some bits of suet in the round-up kettle, to be frying while you cut the ingredients into small pieces. You add the pieces, cover well with warm water, and add hot water from time to time, as needed. Season with salt, pepper, and a little onion. Last of all, you add the brains. Cook until tender, which will take about two hours.” He and all the other experts seem to agree that the result can never be satisfactory unless the cooking begins at the earliest possible moment after the killing of the calf.

Many a one-time cowboy will maintain that there positively is no other dish on land or sea with which this can be compared. Driven to it, he may admit that you can get a mild and altogether imperfect idea of how it tastes by thinking of the best chicken giblets and gravy you ever ate. Serious offense could be given in the old days by claiming that any part of the concoction was better than any other, and it was not etiquette to be in the slightest degree choosey. When it was served from beside the chuck wagon the cook was wont to announce: “Come and get it! Get all you want—but don’t pick!”

John Arnot, also of the Texas Panhandle and a former president of the T Anchor cowboy reunion, who ate his first son-of-a-gun at a Cimarron River cow camp in 1884, observed through the years the reactions of womenfolk to the dish, and was quoted on the subject by the

Amarillo Sunday News

in 1938:

Amarillo Sunday News

in 1938:

“First the ladies act suspicious of it, as if they thought there was something mean and ornery about it—because of the name, I suppose. Then they see everybody eating, and they get a whiff of how it smells, and they say, ‘I believe I’ll take just a small spoonful, please.’ And in a few minutes their plates come back, and they don’t say anything about a small spoonful.”

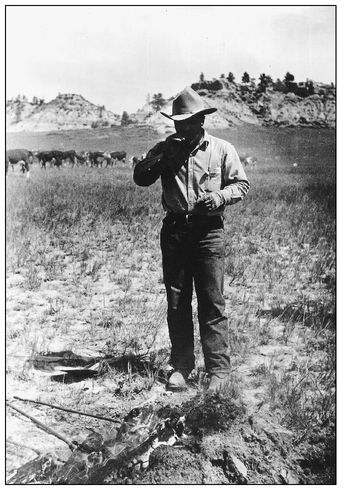

COWBOY EATING “ROCKY MOUNTAIN OYSTERS,” QUARTER CIRCLE U RANCH ROUNDUP, MONTANA. (PHOTOGRAPH BY ARTHUR ROTHSTEIN)

Oklahoma Prairie Oysters

JOHN M. OKISON

In 1938 John M. Okison published his biography of Tecumseh, the Indian leader.

M

ountain oysters, yes; this seasonal by-product of the sheep business is well established in respectable circles as lamb fries. But the prairie oyster, which is eaten by a more limited number of initiates at fall branding time in the cattle country, is not yet to be spoken of freely as a delectable morsel in mixed company. Usually, it is cooked only at branding fires or in kitchens from which women are banished either voluntarily or by diplomatic hints that what is to take place there is wholly a man’s affair.

ountain oysters, yes; this seasonal by-product of the sheep business is well established in respectable circles as lamb fries. But the prairie oyster, which is eaten by a more limited number of initiates at fall branding time in the cattle country, is not yet to be spoken of freely as a delectable morsel in mixed company. Usually, it is cooked only at branding fires or in kitchens from which women are banished either voluntarily or by diplomatic hints that what is to take place there is wholly a man’s affair.

By early November, at the ranches of Oklahoma, whitefaced calves are lusty, fat, and over-ripe for weaning from restive mothers. With these mothers, they are rounded up and driven to a corral; here the cows are separated from their 400-to-600-pound babies and, lamenting, driven back to pasture. To hold the suddenly bereft calves the corral must be stout, for the young ones are as strong, and nearly as agile, as overgrown wildcats; frantic, too, at being deprived of their doting female parents’ attention and their, by now, rather skimpy portions of milk on demand.

With the cows driven far from the scene, three men climb the fence and descend among the milling, bawling mass of calves; the roper, flanker, and branding man. A flip of a three-eighths-inch rope noose over a bull calf’s head, a sudden end-for-end reverse as the calf comes to the end of the rope, a rush by the flanker (by preference, let this one be the professional football tackle type) to wrestle the victim down, then the branding man’s sharp, “Hot iron!” From a chunk fire just outside the corral is yanked the long-handled Lazy-J, or whatever hieroglyphic is required, and handed between the planks of the fence—usually by one of the two boys of fourteen or fifteen always on hand at a branding to tend the fire. The almost red-hot iron is pressed firmly to the young bull’s hip, hair sizzles, a smell that only a cattleman loves fills the crisp autumn air, and the sound of agonized bawling that makes strong women shudder shatters the eardrums.

His branding iron withdrawn from quivering hide and handed outside for re-heating, the cruel branding man assumes the necessary role of destiny. With his big razor-sharp knife, he proceeds to turn a bull calf into a baby beef steer by the only successful process known to man.

As the oysters are removed they are tossed over the fence, to be placed in a tin bucket and kept until the last calf is branded and the last bull calf is “altered.” By now the branding fire is a bed of coals, the irons are hanging on the fence and making their annual brown scar on the wood. There is silence among the outraged new young steers and the twitching, merely-branded heifers. The branding man climbs out of the corral, followed by roper and flanker, all sweat-streaked and grimy. The three stand over the oyster bucket, a hungry light in their eyes; one of the boys mutters, “Gee, they goin’ to

eat

’em?,” and the other boy says, “Sure—wha’dya think!” One after the other, the three men lean to take two oysters from the bucket and toss them on the fire. The branding man suggests to one of the boys, “Bud, go on up to the house an’ get us some salt.”

eat

’em?,” and the other boy says, “Sure—wha’dya think!” One after the other, the three men lean to take two oysters from the bucket and toss them on the fire. The branding man suggests to one of the boys, “Bud, go on up to the house an’ get us some salt.”

The salt comes. With a sharpened stick the roasted tidbits are retrieved; they are split, and salted; when cool enough, they are eaten slowly, with the gusto of seasoned ranch epicures. One boy turns to the other, “Dare you to try one!” “Aw—” and the outcome of their dual of dares and double-dares is always a matter of doubt.

If, as is usually the case, the roper and flanker are from another ranch or from among the hardier of the town drugstore cowboys, the remaining oysters are divided among the three, who make up mental lists of other men to be invited to a feast on the evening when the missus remembers, or is reminded, that she really must go over and have supper with granma.

Oklahoma Kush

K

ush,” popular dish among pioneers: Take cornbread and crumble it up, cut up some onions, add black pepper, a pinch of salt, a little lard or butter, put it in a pan, pour boiling water over it (add eggs if desired), then put in the oven and bake.

ush,” popular dish among pioneers: Take cornbread and crumble it up, cut up some onions, add black pepper, a pinch of salt, a little lard or butter, put it in a pan, pour boiling water over it (add eggs if desired), then put in the oven and bake.

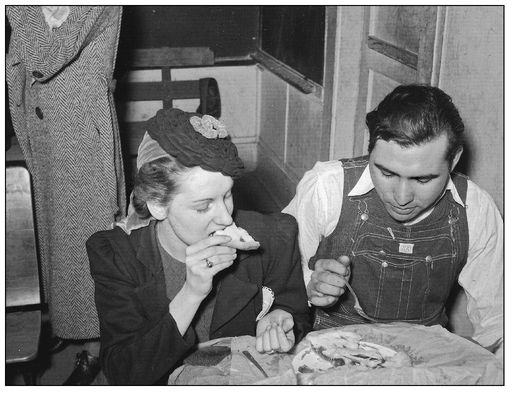

FARM BOY EATING PIE, WHICH HE BOUGHT AT AUCTION AND WHICH WAS MADE BY THE GIRL WITH WHOM HE IS EATING. MUSKOGEE COUNTY, OKLAHOMA. (PHOTOGRAPH BY RUSSELL LEE )

Oklahoma City’s Famous Suzi-Q Potatoes

LILLIE DUNCAN

T

he famous Suzi-Q potatoes originated in Oklahoma City in 1938. The method was worked out by Ralph A. Stephens, owner of Dolores Restaurant and Drive-in. They are now being served in 700 different places, in practically every state in the Union, including the Stork Club in New York City.

he famous Suzi-Q potatoes originated in Oklahoma City in 1938. The method was worked out by Ralph A. Stephens, owner of Dolores Restaurant and Drive-in. They are now being served in 700 different places, in practically every state in the Union, including the Stork Club in New York City.

Café and restaurant operators from San Francisco, from Miami to Boston, and from New Orleans to Montreal are serving these delicious Suzi-Q potatoes.

The cutting machine, made of stainless steel, cuts potatoes in a spiral shape; they are fried in deep fat to a golden brown.

AN INFORMAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Katherine Kellock’s original plan for

America Eats

called for an “informal bibliography” to be created by each state’s Writer’s Project submitting a list of local cookbooks. Most states never sent one, but those that did included many obscure and out-of-print books. Ironically, with the availability of the Internet, today there is a better chance of finding these rare bits of culinary Americana than there would have been at the time of

America Eats

, had it been published in 1942.

America Eats

called for an “informal bibliography” to be created by each state’s Writer’s Project submitting a list of local cookbooks. Most states never sent one, but those that did included many obscure and out-of-print books. Ironically, with the availability of the Internet, today there is a better chance of finding these rare bits of culinary Americana than there would have been at the time of

America Eats

, had it been published in 1942.

Vermont Cookbooks

T

he majority of Vermont cookbooks, or cookbooks used by Vermont housewives, are those brought out by different church societies of the State, supplemented by the innumerable ones offered free by the producers of various food brands.

he majority of Vermont cookbooks, or cookbooks used by Vermont housewives, are those brought out by different church societies of the State, supplemented by the innumerable ones offered free by the producers of various food brands.

For many years

Miss Parloa’s Cook Book

was rated the aristocrat among the many.

The Successful Housekeeper, Lowney’s, Housekeepers’ Guide, The Guide to Good Cooking, Lend-a-Hand Cook Book, The Homekeeper’s Friend

, are even now to be found in Vermont households. Also,

The Universal Common Sense.

Miss Parloa’s Cook Book

was rated the aristocrat among the many.

The Successful Housekeeper, Lowney’s, Housekeepers’ Guide, The Guide to Good Cooking, Lend-a-Hand Cook Book, The Homekeeper’s Friend

, are even now to be found in Vermont households. Also,

The Universal Common Sense.

These all measure up to about the same standard with the same aim, namely, to quote from one of them: “to give the greatest amount of information possible, so arranged that any subject sought can be easily and quickly found and when found shall contain just the information sought.”

The books also tended to emphasize the fact that bad cooking is waste and urged that the rising generation should be taught not to overlook it. Names of contributors were rarely given, as “most of them would be quite unknown and therefore add no authority.”

Cook Books by Texans or Containing Recipes for Texas Foods

NOTE TO EDITOR: The six books here listed are the only notable ones in any list that we have been able to find. In great numbers of Texas communities church cook books have been published, locally and in limited quantities, usually sold at their first printing to members of the church and never available outside the community or listed in any catalogue or library. Such books usually give the favorite recipes of members of the group, but these recipes are not of peculiarly Texas foods except to a very limited extent; each housewife has her own inherited recipes, often brought by her parents from another State. So that even were we able to secure a list of such books, few of them would have any content of value for our purposes.

Title: The Argyle Cook Book.

Author: Alice O’Grady.

Publisher: Maylor Company, San Antonio.

Date: 1940.

Author: Alice O’Grady.

Publisher: Maylor Company, San Antonio.

Date: 1940.

Title: Mammy Lou’s Cook Book.

Author: Betty Benton Patterson.

Publisher: Robert M. McBride and Company, New York.

Date: 1931.

Author: Betty Benton Patterson.

Publisher: Robert M. McBride and Company, New York.

Date: 1931.

Title: First Foods of America

Author: Blanche V. McNeil and Edna McNeil.

Publisher: Sutton House, Ltd., Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York.

Date: 1936.

Author: Blanche V. McNeil and Edna McNeil.

Publisher: Sutton House, Ltd., Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York.

Date: 1936.

(Note: This book contains recipes for Texas-Mexican foods.)

Title: Home Cooking

Author: G. L. Nelson

Publisher: Nealen Sales Service, San Antonio.

Date: 1934.

Author: G. L. Nelson

Publisher: Nealen Sales Service, San Antonio.

Date: 1934.

Title: Menus and Recipes

Author: M. Gleason.

Publisher: Extension Department, College of Industrial Arts, Denton, Texas.

Date: 1928.

Author: M. Gleason.

Publisher: Extension Department, College of Industrial Arts, Denton, Texas.

Date: 1928.

Title: Cooking Recipes of the Pioneers.

Author and Publisher: Under the auspices of the Bandera Library Association,

printed by Frontier Times Magazine, Bandera, Texas.

Author and Publisher: Under the auspices of the Bandera Library Association,

printed by Frontier Times Magazine, Bandera, Texas.

Other books

Firewalker by Josephine Angelini

House of Evidence by Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson

Locked by Morgan, Eva

I Am Scout by Charles J. Shields

A SEAL's Oath (SEALs of Chance Creek Book 1) by Cora Seton

The Year's Best Horror Stories 7 by Gerald W. Page

A Time To Kill (Elemental Rage Book 1) by Jeanette Raleigh

Elegy (A Watersong Novel) by Hocking, Amanda

Soulbinder (Book 3) by Ben Cassidy

Liaison by Natasha Knight