The Food of a Younger Land (46 page)

Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

Menudo is good, wholesome and nourishing, his mother often said. To feed so many relatives and friends menudo would provide a delightful meal at comparatively less cost. Besides, who is the Mexican who does not relish menudo? When Mike’s family wants to eat menudo, there’s always the problem of buying the entire tripe of a beef. It weighs from fifteen pounds or more. It comes already cleaned and dressed for cooking from the slaughter-house. In the old days a Mexican family killed their own beef, that was at a special fiesta or celebration. So when a Mexican family wants to eat the delicious menudo it was best to get all the relatives together and all the friends.

On the afternoon of the twenty-fourth, Mike brought home the tripe, the whole entrails of a beef, including the intestines. They were white and cleaned. His mother and his wife washed the tripe over to be sure it was thoroughly clean. Mike’s wife has heard that if you soaked it in salt-water it would be cleaner. The mother agreed, although she explained the menudo would taste better with full flavor of the tripe in it. When they were satisfied the tripe was well cleaned, they chopped it up in small pieces, piling it over in a large basin.

Before they had their supper, they had already started boiling the tripe in a huge kettle or cauldron. The tripe has to boil at least four hours. Sometimes when it has been boiling long enough they pour in corn (hominy) and flavor it with pepper and salt to taste. By midnight the menudo would be tender and tasty enough to eat. The hominy would then be so steeped in the juice of the tripe and the tripe cooked in the corn that both make a complete and appetizing meal.

Mike took his wife and mother to the Midnight Mass. His mother always takes her Communion, and the three of them took Communion on this important holiday. When the Mass was over, the air had become chilly. It was good to hurry home. On the way they met some of their friends and they went home together. Aunts and uncles with the children and in-laws began coming, coming from the Mass. They exchanged felicitations.

On the table were set glasses and wine and tequila or brandy. Mike began filling the glasses up and distributing drinks around. Many preferred wine, and more wine. Port, said one of Mike’s uncles, is also good for the health. But what the entire party was interested most in was the hot menudo, which they could smell—mealy and brothy.

Mike’s wife, assisted by her friends, dished the menudo in wide bowls. It was steaming hot. It is best to eat menudo while it is hot, when you could get the full goodness and flavor of it. Among the tripe bits, curled and tender, swam bursting corn kernels, swollen with the rich soup of the tripe. The soup glistened with globules of fat and substance boiled out of the tripe. One could hardly wait for it to cool before one sipped it. Ah! sighed Mike’s uncle, there’s nothing like menudo for a good meal of a chilly evening. You can feel it warm inside you and feel its strength nourishing your body. It peps you up.

But one of Mike’s aunts stared at her bowl with an air that did not agree with Mike’s uncle. She had in her bowl mostly soup and drifts of corn. She wanted to tell Mike’s uncle that no wonder he appreciated his bowl of menudo so much—he had a bowlful of the tripe itself. But she remembered her manners and kept her peace. However, it would break no etiquette to accept a second bowl and one could suggest that she could do with a lot of tripe. It is always understood that everybody relishes menudo, and one could eat all one can.

When one eats menudo, one seasons it with crushed herb seasoning and chile. The herb seasoning may be enough for those who could not stand the stinging hotness of chili sauce. Mike shook chili sauce in his bowl until it turned deep pink. When he ate it, his face flamed up very red, water starting in his eyes. One may season his menudo to his individual taste—and capacity for endurance. Bread was served with the menudo for anyone who wanted it and [was] not satisfied with eating the bready hominy in the soup. Coffee and dessert came next.

Tucson’s Menudo Party

T

o celebrate the world’s premiere of the movie

Arizona

, filmed in Tucson, the town held a public menudo party after the first show. For fifty cents, one could eat all he wanted of menudo. But on the night of the menudo party, they served bowls of menudo to whoever came and wanted to eat. Tucson intends to hold menudo parties during the town’s festivals and during the Rodeo day—menudo at night and barbecue at day time. The movie personalities and the excitement of the first world premiere the town ever had so dazzled the midnight menudo party that it is hard to draw a balanced perspective of the actual menudo eating part of the party. It seemed that the public was too excited to appreciate the flavor and appetizing values of the menudo. The menudo party was better reading at the time the publicity releases were published. From corners of the nation requests were made for the menudo recipe.

o celebrate the world’s premiere of the movie

Arizona

, filmed in Tucson, the town held a public menudo party after the first show. For fifty cents, one could eat all he wanted of menudo. But on the night of the menudo party, they served bowls of menudo to whoever came and wanted to eat. Tucson intends to hold menudo parties during the town’s festivals and during the Rodeo day—menudo at night and barbecue at day time. The movie personalities and the excitement of the first world premiere the town ever had so dazzled the midnight menudo party that it is hard to draw a balanced perspective of the actual menudo eating part of the party. It seemed that the public was too excited to appreciate the flavor and appetizing values of the menudo. The menudo party was better reading at the time the publicity releases were published. From corners of the nation requests were made for the menudo recipe.

When John Walton Became Governor of Oklahoma

F

rom:

High Lights in the Life of John (Jack) Galloway Walton

, by F. A. Ruth:

rom:

High Lights in the Life of John (Jack) Galloway Walton

, by F. A. Ruth:

“Jack Walton was elected Governor of Oklahoma by the largest majority ever given a candidate up to that time. His inauguration was featured by the famous Jack Walton barbecue, Jan. 8, 1923, the largest event of its kind ever held in the world’s history. It lasted for three days, during which time square dancing, fiddlers’ contest, and free amusements of all kinds were had. For the barbecue, there were built there 10,000 gallon coffee pots that required the steam from six steam fire engines to keep them boiling. Three carloads of coffee were used, and 300,000 tin cups were distributed in the crowds. More than a mile of trenches were dug for barbecuing the meat, which consisted of one carload of Alaskan reindeer, one train load of cattle, chickens, rabbits, and buffalo. One carload of pepper [!] and one carload of salt were used for seasoning. Two hundred and fifty thousand buns were used. The official checkers counted over 250,000 guests who participated.”

From: Okla. City

Daily Oklahoman

, Jan. 10, 1923:

Daily Oklahoman

, Jan. 10, 1923:

“When I am elected governor, there will not be any inaugural ball, and there will not be a ‘tea dansant.’ I am going to give an old-fashioned square dance and barbecue; it will be a party for all the people, and I want you all to come!”

That statement was repeated in each of the 400 campaign speeches of J. G. (Jack) Walton, the candidate. Tuesday [Jan. 8, 1923], his second day in office, Walton, the Governor, had fulfilled that pledge to the utmost and one of the greatest crowds [100,000 or more] ever assembled in Oklahoma [at the State Fair Grounds] stood by to see him make good the first of his campaign pledges . . .

War Dance StagedAt the fair grounds there was color aplenty. Dick Light, soloist with the Walton campaign party, sang “Old Pal, Old Pal,” at the request of the “Bryan County 5,000.” An Indian war dance was staged in front of the grand stand, with Zack Mulhall whirling about on a sweat-streaked steed. Eugene Naple, the 10-year-old orator from Grandfield, delivered a eulogy to the new governor. Senator Robert L. Owen, through the loud speaker, expressed the “greatest hope, the greatest faith, in the success of Jack Walton . . .”

More than 60,000 are fed by:

Barbecue MeatStreaming endlessly through the fifteen serving units, rich man, poor man, women with sealskin coats and diamonds, farm wives and children, swelled the total fed at the barbecue to approximately 60,000 at sundown, according to John R. Boardman, chairman of the serving committee. Fifteen lines of humanity were still surging through the openings and passing the little windows where barbecued beef, bear, deer, rabbit, turkey, chicken and reindeer were being passed out on paper plates with buns, pickles, onions and sugar at dark.

Meat Served All Night“They will be fed as long as it lasts. Another shift of workers is going on and we will continue serving all night,” Boardman said.

The first rush started at 12:30 o’clock and for thirty minutes the mammoth crowd, without guidance, “swamped” the 165 busy workers who were filling plates for the hungry. In thirty minutes the National Guardsmen were thrown in to control the tidal wave of humanity which was soon formed into the fifteen lines which continued pouring through the serving units until late Tuesday night.

“Hot Dawg, some barbecue!” declared a youth . . .

Fifteen Plates a MinuteFifteen plates a minute at each unit were passed out to the visitors, Boardman said. Arrangements were made to serve a plate a second, but the meat could not be sliced fast enough and brought in huge army trucks to the serving units. However, fifteen is a conservative estimate and probably 80,000 persons will be fed before the night is over, Boardman thinks.

Eight girls, two men and a captain at each unit, marshalled by Mrs. Will Owens, sliced pickles and onions, filled plates and passed them out the little windows provided at the fronts of stock sheds.

Mother Earth Serves as TableBaby was robbed of his blanket, overcoats, papers and most anything available were used by the guests who broke the bread of Oklahoma’s governor to sit on the ground and consume the feast. The large basin on the east end of the grounds was black with people who used “Mother earth” as a festive board for the meat and the tin cup as a goblet for the drink [coffee from a battery of 10,000-gallon metal tanks] provided to celebrate the inaugural.

Oklahoma Scrambled Eggs and Wild Onions

I

n the eastern, Indian, section of Oklahoma housekeepers watch eagerly for the appearance, in late February or early March, of Indian wild onion gatherers. Their neatly tied bundles are chopped, cooked briefly, then mixed in the skillet with enough eggs to make a family feast. To be invited to such a dinner is an experience not soon forgotten.

n the eastern, Indian, section of Oklahoma housekeepers watch eagerly for the appearance, in late February or early March, of Indian wild onion gatherers. Their neatly tied bundles are chopped, cooked briefly, then mixed in the skillet with enough eggs to make a family feast. To be invited to such a dinner is an experience not soon forgotten.

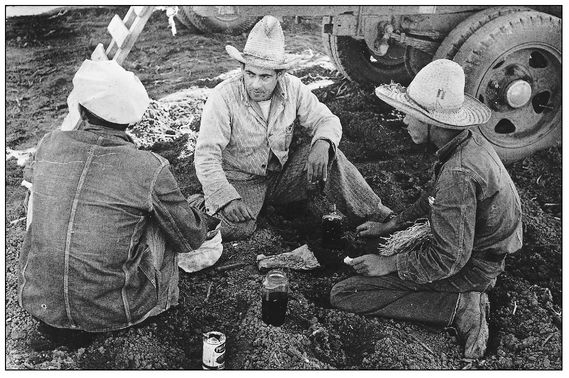

MEXICAN LABOR CONTRACTOR IN CENTER WITH TWO CARROT WORKERS EATING “SECOND BREAKFAST” NEAR SANTA MARIA, TEXAS. (PHOTOGRAPH BY RUSSELL LEE )

Texas Chuck Wagon

W

herever, throughout the ranching areas of the Southwest, there is a reunion of cattlemen, ex-cowboys, or old trail drives, a feature of the gathering is almost certain to be a meal that centers around an old-time chuck wagon.

herever, throughout the ranching areas of the Southwest, there is a reunion of cattlemen, ex-cowboys, or old trail drives, a feature of the gathering is almost certain to be a meal that centers around an old-time chuck wagon.

It had no other name, this essential of the cattle industry in range days—a field kitchen that accompanied the cow-waddies on their chores of rounding up, branding, driving, and otherwise conditioning cattle for the market. It went with the men and their herds, even on the epic treks of the trail drives to northern markets. Of roads there were few or none. The chuck wagon moved from day to day over every kind of terrain across which a cowboy could ride a horse or drive a steer.

In this modified prairie schooner the cook was a monarch. His domain included a circle around his stronghold, a radius of about sixty feet, but varying with cooks and local customs. At the back of the wagon was a let-down shelf from which the hungry cowboy took his eating tools and such foods as the cook saw fit to hand out there. He then went over to the fire and helped himself to whatever else had been concocted or brewed for his sustenance.

Except for rare feasts, generally before round-ups, the meals were plain and monotonous—beans, salt pork (usually “side-meat,” modernly called bacon), fresh unfattened beef from the range, and sourdough biscuits. Various criteria were used in judging chuck-wagon cooks, but it is generally agreed that in the evaluation of these always important personages, good sourdough biscuits would cover a multitude of other sins, for sourdough biscuits were the bread of life of the Texas plains.

Into their construction the competent range cook put time and loving care. He started, usually, with a potato, some sugar, and a little flour. These—the potato being grated—were worked together until smooth and set in a warm place to ferment—often, under range conditions, being wrapped in a blanket and placed near the fire. When the dough had risen, more water and flour were kneaded in, together with salt, soda, and sugar if required. The mixture having reached the proper smoothness, pieces were pinched off and moulded in the hollow of the hand. Dutch ovens were preferred for baking. Shoved into hot ashes and covered with ashes and coals, they became hot and held their heat, and the bread could be baked in them without danger of burning.

Surrounded as he was by the great open spaces and without much companionship—the men that he served appeared from their range labors only at mealtimes, and he seldom saw anyone else—the genius who reigned at the chuck wagon sometimes felt the urge to let his visions roam beyond the dull routine of his daily vocation, to dream artistically of menu complexities that might be accomplished within the limitations of his normal materials. Such an artist evolved a dish that today, in one of several similar forms, is the main feature of every chuck-wagon banquet.

Precisely how and why it gained its original name has been lost in the mists of antiquity, and that name, in the interest of politeness, has long since been amended. Except by the older cattle set—and by them only on rare and wholly masculine occasions—it is now called son-of-a-gun stew.

Other books

Uphill All the Way by Sue Moorcroft

Pride Unleashed (a Wolf's Pride novel, book 2) by Kalen, Cat

Baron's Last Hunt by S.A. Garcia

Long Upon the Land by Margaret Maron

Cora Ravenwing by Gina Wilson

The Slow Natives by Thea Astley

A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962 by Alistair Horne

Shardik by Adams, Richard

The Darkest Pleasure by Gena Showalter

Whipple's Castle by Thomas Williams