The Food of a Younger Land (42 page)

Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

At length, after everyone has had his fill, the coffee and cakes are served. There are plain and fancy cakes, devil’s food and angel food cakes, walnut, spice, and banana cakes. And lest cake alone should fail to appease the crowd’s sweet tooth, there are all kinds of pies. These fall into three classifications: Open face, crisscross, and “hunter’s case,” their tasty fillings limited only by the whims of their makers. These consist of pumpkin, gooseberry, loganberry, lemon, cream, banana, and cherry.

Following the repast, the picnickers stroll away to engage in one activity or another; some resume their interested chats, many spend their time visiting, while others make their way to the speakers’ stand to take part in the afternoon program. Here C. H. Parsons, before introducing the speaker of the day, goes through the ritual of detailing his experiences as a regular attendant of every Iowa picnic since the first one was held in the Raymond Hills of Pasadena in 1900. Further entertainment for the picnickers is provided by bands, singers, and cowboy minstrels.

Later on, when the first shadows of evening begin to fall across the greensward, hampers and other food containers are again brought forth for one last snack before the picnickers call it a glorious day and wend their way homeward.

Approved by C. H. Parsons, Secy. Iowa State Assoc., 12-31-41

Food à la Concentrate in Los Angeles

DON DOLAN

T

here was a day when every diet-conscious person chanted “calories.” . . . “Ya gotta watch your calories.” Today the litany is “vitamins and minerals,” a creed gaining more adherents every day. In the robust manner in which Americans accept the new, a principle of real dietary value has ballooned into that fabled panacea, the Elixir of Life.

here was a day when every diet-conscious person chanted “calories.” . . . “Ya gotta watch your calories.” Today the litany is “vitamins and minerals,” a creed gaining more adherents every day. In the robust manner in which Americans accept the new, a principle of real dietary value has ballooned into that fabled panacea, the Elixir of Life.

Nowhere is this so evident as in the Los Angeles area, the most important center for all Health Food activity.

From here, thirty firms grind and pack capsules and tablets of pulverized vegetable mixtures, and ship these out in a constant stream to treat the ungastronomic tongues of the nation. Here numerous retail stores, unofficial consultants on your bodily needs, greet you with the hushed cheer of a mortician, help you to select your herb tea, your nonsugar candies, your powdered vegetable mixture most suited to your particular form of astigmatism or gout or midafternoon slump. Here many restaurants cater to the intent determination of the teeming dietists, all of whom have become health authorities from a two-week wishful reading of advertising pamphlets.

Despite the exaggerated fervor in search of the optimum in food content, much good already has developed. A thiamin (Vitamin B

1

) deficiency in the body results in nervousness, and people with no pep can not put forth their best efforts in national defense. It was found that our bread lacks the thiamin it should contain, because the refining of the flour milled out this priceless ingredient. Bakers now offer us “enriched” bread: loaves to which have been added a proper proportion of chemically produced thiamin. So that even though, in the traditional humorless manner of American big business, artificial Vitamin B

1

must be added to replace the natural Vitamin B

1

which had once been there, still the result is an improvement in national diet.

1

) deficiency in the body results in nervousness, and people with no pep can not put forth their best efforts in national defense. It was found that our bread lacks the thiamin it should contain, because the refining of the flour milled out this priceless ingredient. Bakers now offer us “enriched” bread: loaves to which have been added a proper proportion of chemically produced thiamin. So that even though, in the traditional humorless manner of American big business, artificial Vitamin B

1

must be added to replace the natural Vitamin B

1

which had once been there, still the result is an improvement in national diet.

Knowledge that foods could satisfy the appetite without satisfying the bodily needs took place long ago in the British Navy. Seamen got a sufficient quota of salt pork and bully beef and potatoes and hardtack—but they still developed scurvy. The addition of lime juice to their diet prevented this, leaving these “limeys” more alert. The principle had been proved: foods can lack oomph.

Chicago Dr. J. W. Wigelsworth in 1920 got tired of preaching to his patients: “Eat more vegetables—lots and lots of them.” They would agree that vegetables probably were good for them, but they would not bother to eat them. So the doctor started some experiments, to the dismay of the clean-kitchen instincts of his household. For days he kept the oven full of chopped vegetables. Then, when the water content had evaporated, he laboriously mashed the residues with mortar and pestle. The result was something pretty tasteless and lacking in that fine eye appeal; but a spoonful of it was the equivalent of a bale of the raw product. Of course, eaten even with a liberal sluicing of water, it went down hard and tended to gag. But when poked into a gelatin capsule, the doctor’s patients would swallow it faithfully. After all, they were accustomed to having their medicines in pellets. And the stuff helped them: Through the course of his clinical experiments, Dr. Wigelsworth evolved the formulae for several combinations of vegetables which seemed particularly effective in the treatment of particular maladies of his patients.

With more knowledge of engineering and promotion, his brother constructed an arrangement of ovens by which the drying-out process could be accomplished for a lot of vegetables at once. The result was the Anabolic Food Products, Inc., with a factory in Glendale and sales offices in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York.

The possible combinations of foods applicable to specific human ills have grown to number forty-three items that are now prepared and marketed by Anabolic. Aware of the flagrant misuse to which any remedy often is put, Anabolic furnishes its preparations only through the medical profession, acting somewhat in the capacity of a doctor to doctors.

Would you like a pretty pill of endive, Cape Cod cranberries, Irish kelp, and garlic: Anabolic probably has it. Of course, it will not look like anything but a capsule of brown powder, but it has guts. When did an eye for nutrition ever have to be also the lyric eye of a Brillat-Savarin?

Beneath the professional reticence common in the field of medicine, one gathers that Anabolic sees too much enthusiasm with too little common sense of health applied in the general field of health foods.

Not long since, an eastern doctor stopped at a Central Market stand selling vegetable juice extractors. In the pure whine of a barker, the clinically clad attendant “proved” that his juicer was best, because “See this vegetable? See the vitamins crawling all over the skin? Put through an ordinary juicer, all these vitamins are thrown away. I have seen it. Now watch! When I put it in this juicer, all the vitamins go right into the juice, where you have them to drink to get healthy and young again.”

In the health-food restaurants, tables are supplied with nothing as ruinous as sugar, salt, pepper. There will be a bowl of raw sugar, which looks like brown sugar caught in the damp. The two shakers will contain 1) alfalfa dust, and 2) sodium glutaurate, which gives color to your food. A popular dish is a vegetable salad sprayed with a dressing of mixed lemon juice and honey. A wheat-germ porridge is another favorite. This being southern California, there will be a health version of a Spanish omelet. For dessert, you may have your choice of carrot ice cream or ice cream with pollenless honey. You will drink a soy concoction which looks like boiled-down roily water off a red clay-bottomed brook—and tastes like just plain mud—and probably have a side order of soy beans prepared in parched form.

These restaurants are almost all cafeterias. One reason for this may be so that the diner can select what dishes he wants so as to balance his own meals unless it is that he would not possibly choose such dishes by their truthfully unappetizing names, so that they must be seen to be believed and picked. Another reason probably is that steamable style is more informal, promotes more friendliness among the patrons, most of whom are there partially to find a group sympathetic to their own habits of eating and vitamin-chart existence.

The health-food cult has developed a language all its own. Until you are initiated into the mysteries of the mineral and the vitamin, you are apt to blink at a restaurant listing its offerings as “live” or “raw” foods. Involved words to describe other phases of the field are built up from obscure Greek or Latin roots, suggesting the mythology from which they spring.

But, filtering out the candor from the cant, there emerge hygienic truths in the health-food business. And nutritional satisfaction need not mean gustatory grief. Much food value that had been discarded from carelessness now begins to make an appearance in the dishes we eat; and tastes lose no pleasure from joining hands with dietary satisfaction. Food specialists today are giving serious consideration to the advantage of dehydration to reduce awkward bulk in both army rations and civilian fare.

Los Angeles! Where religion turns into thousands of obscure cults; where by street dress men and women merge into a common sex; and where the fine art of eating becomes a pseudo scientific search for a lost vitality hidden in the juice of a raw carrot.

Sources: Dr. Fowler, Anabolic Food Products, Inc., Glendale, California, and personal observation.

A Los Angeles Sandwich Called a Taco

DON DOLAN

N

aturally, the Mexican influence pervades southern California sandwiches. Given the Mexican

tortilla

—the plate-sized wafer of powdered corn—along with beans and chili, and you have the ingredients for a sandwich called a

taco

: a

tortilla

fluttered through hot grease, folded around shrimp, sausage, and chili stew, garnished with shredded lettuces and grated cheese. A finger-size

taco

from Olvera Street bears the baby name of

taquito

.

aturally, the Mexican influence pervades southern California sandwiches. Given the Mexican

tortilla

—the plate-sized wafer of powdered corn—along with beans and chili, and you have the ingredients for a sandwich called a

taco

: a

tortilla

fluttered through hot grease, folded around shrimp, sausage, and chili stew, garnished with shredded lettuces and grated cheese. A finger-size

taco

from Olvera Street bears the baby name of

taquito

.

Another variety, the

tostadita

, results when a small

tortilla

is toasted deep brown, edges crimped in a ridge around the filling, arranged on the plate with shredded lettuce and sliced radishes, and served steaming hot.

tostadita

, results when a small

tortilla

is toasted deep brown, edges crimped in a ridge around the filling, arranged on the plate with shredded lettuce and sliced radishes, and served steaming hot.

Chalupa

means a canoe for two . . . soft night—rippling water—a man and a maid. But even love feels the pangs of hunger, so a

chalupa

becomes a curled-edge

tortilla

fresh from sizzling fat, filled with beans, avocado, green chili, minced onions, chili stew, and sprayed with a piquant tomato sauce. Romance thrives on that.

means a canoe for two . . . soft night—rippling water—a man and a maid. But even love feels the pangs of hunger, so a

chalupa

becomes a curled-edge

tortilla

fresh from sizzling fat, filled with beans, avocado, green chili, minced onions, chili stew, and sprayed with a piquant tomato sauce. Romance thrives on that.

The

burrito

, simplest Mexican sandwich, calls for a

tortilla

wrapped like a jelly roll around beans. Or, more elaborately, it takes the form of a club sandwich filled with avocado and the white meat of chicken.

burrito

, simplest Mexican sandwich, calls for a

tortilla

wrapped like a jelly roll around beans. Or, more elaborately, it takes the form of a club sandwich filled with avocado and the white meat of chicken.

Los Angeles—American edition—retains the art of the sandwich; in so doing, it is guilty on at least three counts of providing the piece de resistance of an eat-and-run meal.

Of these, two came from restaurateur De Forest, whose colorful business name evolved from the jests of customers. It metamorphosed from “T. N. De Forest” through “Female Tommy” to “Texas Female Tommy’s Ptomaine Tabernacle,” whence it crystallized into the unforgettable “Ptomaine Tommy’s.”

“Size” was the happy thought born of hunger in Ptomaine Tommy. Proprietor of a lunch wagon in 1915, on the North Broadway fringe of Mexican town, he of necessity provided his own board—and became very tired tasting the few available dishes. In a need of pure experiment he strewed chili and beans over a hamburger steak, and covered the whole with chopped onions.

Curious customers saw it, asked for it, liked it, and then demanded it. They would order, from the degree of their hunger, according to how big a cake they wished of the ground beef which forms the basis of the dish. Thus, “hamburger size” or “steak size.” The name generally settled to “size,” with the larger version becoming an “oversize,” and the Ptomaine Tommy sprinkling of chopped onions on it, called a “shower.” “Size” remains the chef-d’oeuvre of the new restaurant to which it gave birth, and has been widely copied.

Trial and error also produced the Ptomaine Tommy specialty of “Egg Royal Decorated.” A butter-fried mixture of egg and ground beef—seemingly known as Denver or Western sandwich—is “decorated” with chili beans.

From Los Angeles comes the “French-dipped” sandwich, a quick lunch developed to satisfy the appetites of hard-working factory hands. Two Italian brothers named Martin, who in 1921 operated a day-and-night sawdust-floored delicatessen-counter restaurant under the French name of “Philippe’s,” were the creators. From an

au jus

base they concocted a sauce from a secret Philippe formula. Generous slices of good roast meat are spread on half a fresh-baked French (longish, crusty) roll, the cover half being dipped liberally in the sauce.

au jus

base they concocted a sauce from a secret Philippe formula. Generous slices of good roast meat are spread on half a fresh-baked French (longish, crusty) roll, the cover half being dipped liberally in the sauce.

The French-dip sandwich has spread to lunchrooms all over the country, gustatory proof of its appeal; and to the original Philippe’s—still in its lowly warehouse district home—comes a continuous and popular pilgrimage of sandwich connoisseurs.

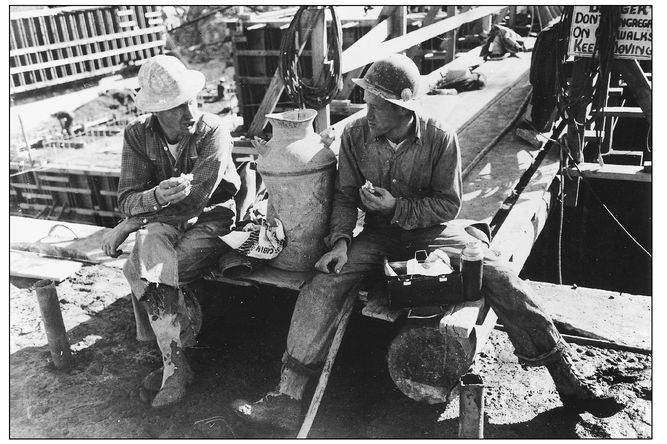

CONSTRUCTION WORKERS EATING LUNCH AT THE SHASTA DAM. SHASTA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA. (PHOTOGRAPH BY RUSSELL LEE)

A California Grunion Fry

CHARLES J. SULLIVAN

California grunion, a specific species known in science as

Leuresthes tenuis,

are sardine-sized silver fish. At mating time the females come up on the beach and dig their tails into the sand to lay their eggs. A male then curls around the female to deposit his sperm. The grunion eggs remain hidden in the sand until the eggs hatch at high tide and the young grunion are washed out to sea.

Leuresthes tenuis,

are sardine-sized silver fish. At mating time the females come up on the beach and dig their tails into the sand to lay their eggs. A male then curls around the female to deposit his sperm. The grunion eggs remain hidden in the sand until the eggs hatch at high tide and the young grunion are washed out to sea.

Other books

The Way Some People Die by Ross Macdonald

Bitter Black Kiss by Clay, Michelle

Night Reigns by Dianne Duvall

Selected Poems 1930-1988 by Samuel Beckett

Shadows Linger by Cook, Glen

The News from Spain by Joan Wickersham

Views from the Tower by Grey, Jessica

The Girl From Ithaca by Cherry Gregory

Invisible Girl by Mary Hanlon Stone

Catch as Cat Can by Rita Mae Brown