The Forgotten Trinity (16 page)

Two main ideas will help us to get a handle on Gnostic belief. First,

the very term "gnosticism" comes from the Greek term gnosis,2 meaning "knowledge." Devotees of Gnostic thinking believed that salvation

was primarily a matter of obtaining certain knowledge (normally available only through their particular group, often disseminated by secret

rituals). This knowledge, in turn, allowed a person to "escape" from

the corruption of the world and their physical bodies.

Second, Gnostic belief was marked by dualism. Dualism is the idea

that what is material (matter, flesh, the world) is inherently evil, while

that which is spiritual (the soul, angels, God) is inherently good. Much

of Greek thought was dualistic in nature. Salvation was found through

"escaping" the body, for it was believed that man is basically a good

spirit trapped inside an evil body. This is one of the reasons that when

Paul made mention of the resurrection in his sermon on Mars Hill

(Acts 17:32) they began to mock, for anyone who sees salvation as

being freed from the body will hardly find the message of the resurrection of the body to be good news.

The acceptance of dualism led to two extremes of behavior. Some

became ascetics, depriving the body through fasts and monastic living,

often demanding that followers abstain from sexual conduct, even to the

point of forbidding marriage. For some strange reason, these groups

often died out in a couple of generations. On the other extreme, you had

the hedonists who reasoned that since the goal of salvation was to be rid

of your physical body, and since your spirit really wasn't impacted by what your body did, why not just have fun, eat, drink, and be merry?

These folks would engage in extremes of immorality, figuring that what

the physical body did was irrelevant to the pure, immortal "soul."

Most important for our study and for the background of Colossians is the question of how the Gnostics explained the creation of the

world. If you think about it, you see they had a problem. If all matter

is evil, how could the pure, good God of Gnosticism be responsible

for the creation of evil matter? Over time they developed an elaborate

scheme to explain how evil matter made its appearance in the universe.

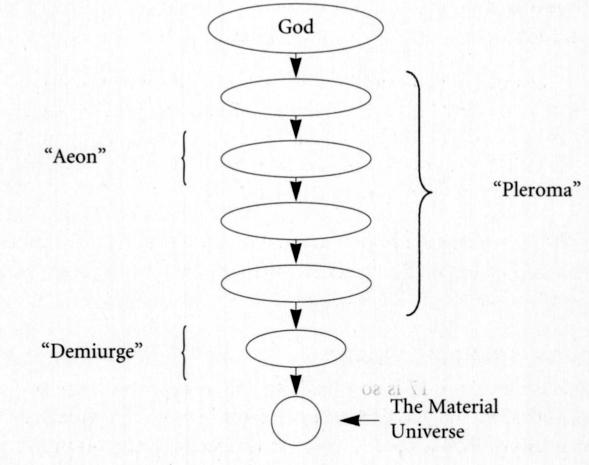

As it is a bit complex, I provide a graphical explanation below.

We begin with the good, pure, spiritual God at the top of the diagram.

From this one true God flows a long series of "emanations" known to

the Gnostics as "aeons." These aeons are godlike creatures, often identified as angels when Gnosticism encountered Jewish or Christian beliefs

(possibly alluded to in Colossians 2:18). All of the aeons, taken as a

group, comprised the "pleroma," the Greek word for "fullness ."3 Each of

these aeons along the line of emanation from God is a little less "pure,"

a little further away from the one true God. Eventually, the line extends

far enough that you encounter the "Demiurge," a divine being who has the capacity to create and is sufficiently "less pure" than the true God so

as to create, and come in contact with, matter. In the second century of

the church's history, some Gnostic teachers identified this evil Demiurge

with the God of the Old Testament, Yahweh.

One other element of Gnostic teaching and influence should be

noted. The concept of dualism led to one of the most forcefully denounced heresies of the apostolic era: Docetism. The Docetics were individuals who denied that Jesus had a real physical body. They were called

Docetics because the Greek term dokein' means "to seem." Hence, Jesus

only seemed to have a physical body, when in fact He didn't. As we noted

earlier, Docetics would tell stories about Jesus and a disciple walking by

the seashore, talking about the mysteries of the kingdom. At some point

the disciple would turn around and look back upon their path and discover that there was only one set of footprints. Why? Because Jesus

doesn't leave footprints, since He only seemed to have a physical body.

One can easily see why the Docetics believed as they did. They were dualists, influenced by the Greek concept of spirit and matter. If they affirmed that Jesus was truly good, they could not believe He was truly

human with a physical body, since the body is evil. It is plain that there

were Docetics around during the time of the apostles, for John left no

uncertainty as to his view of their teaching:

By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit that confesses

that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God; and every spirit

that does not confess Jesus is not from God; this is the spirit of

the antichrist, of which you have heard that it is coming, and now

it is already in the world. (1 John 4:2-3)5

With this background, we can now listen to Paul's words and test

the various interpretations that are offered of his teachings in Colossians 1:l5ff, as well as in Colossians 2:9.

IMAGE AND FIRSTBORN

Colossians 1:15-17 is so often cited by so many different groups,

both orthodox and heretical, that we must be very careful to look as

closely as possible at the text so as to be able to give a proper, God honoring, consistent, and truthful answer to those who ask us concerning our belief in Christ as the eternally preexistent Creator of all things.

A few points here might seem complex or obscure. However, keep in

mind that the cultic groups that deny the deity of Christ are often well

prepared to utilize this passage to their benefit. Knowing the passage well

is your first line of defense in seeking to speak God's truth in love. Paul

obviously felt it necessary to go into detail on this topic, so we should

be prepared to work just as hard to understand his teaching.

And He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all

creation. For by Him all things were created, both in the heavens

and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions

or rulers or authorities-all things have been created through Him

and for Him. He is before all things, and in Him all things hold

together. (Colossians 1:15-17)

At first glance, it seems obvious that we are describing the Creator

in this passage. Yet many groups attempt to derail what seems like the

obvious meaning of the passage by pointing out that verse 15 describes

the Son as the "image of the invisible God" and as the "firstborn of all

creation." Those who do not understand the doctrine of the Trinity

will assert, "See, He's the image of the invisible God, not the invisible

God himself," wrongly assuming that we believe the Father (the "invisible God") and the Son to be the same Person. In response, we point

out that no creature can be the image of the invisible God, at least not

in perfection. The Bible likewise describes Christ in similar language

when it says that He is the "exact representation of His nature" (Hebrews 1:3). The Son can perfectly reflect the nature of God, and be the

perfect image of the Father, because He, like the Father, is eternal and

unlimited in His deity.

But what of the term "firstborn"? Many groups place heavy emphasis upon this term, though often for different reasons. Normally,

the use of the term falls into two categories:

1. Those who deny the deity of Christ will insist that the term indicates

origination, creation-a beginning in time. These groups will insist that

the passage is teaching that the Son is the first thing created by God, or the first element of the rest of creation. For most of these folks,

"firstborn" is taken as completely synonymous with "first created."

2. Those who believe this refers to some kind of relationship between

the Father and the Son that indicates an inferiority on the Son's part.

Mormons, for example, take the term to refer to the idea that the Son

was begotten by the Father in a premortal existence, making the Son

a second God, separate from the Father.

The first major task in properly addressing this passage is dealing

with the meaning of the Greek term prototokos (firstborn) 6 When Paul

wrote this letter and used this term, what did he intend? How would

his readers have understood him?

First, it is important to realize that this term already had a rich

background in the Greek Old Testament, the Septuagint (LXX).' It appears there approximately 130 times, about half of those appearances

coming from the genealogical lists of Genesis and Chronicles, where

it bears the standard meaning of "firstborn." But it has a much more

important usage in a number of other passages. The "firstborn" was

entitled to a double portion of the inheritance or blessing (Deuteronomy 21:17; Genesis 27), and received special treatment (Genesis

43:33).

That firstborn came to be a title that referred to a position rather

than a mere notion of being the first one born is seen in numerous

passages in the Old Testament. For example, in Exodus 4:22 God says

that Israel is "My son, My firstborn." Obviously Israel was not the first

nation God "created," but is instead the nation He has chosen to have

a special relationship with Him. The same thought comes out much

later in Jeremiah 31:9, where God again uses this kind of terminology

when He says, "For I am a father to Israel, and Ephraim is My firstborn." Such language speaks of Israel's relationship to God and

Ephraim's special status in God's sight.

But certainly the most significant passage, and the one that is probably behind Paul's usage in Colossians, is Psalm 89:27: "I also shall

make him My firstborn, the highest of the kings of the earth." This is

a highly messianic Psalm (note verse 20 and the use of the term

"anointed" of David), and in this context, David, as the prototype of the coming Messiah, is described as God's prototokos, the "firstborn."

Again, the emphasis is plainly upon the relationship between God and

David, not David's "creation." David had preeminence in God's plan

and was given leadership and authority over God's people. In the same

way, the coming Messiah would have preeminence, but in an even

wider arena.

When we come to the New Testament,8 we find that the emphasis

is placed not on the idea of birth but instead upon the first part of the

word-protos, the "first." The word stresses superiority and priority

rather than origin or birth.9 In Romans 8:29, the Lord Christ is described as "the firstborn among many brethren." These brethren are

the glorified Christians. Here the Lord's superiority and sovereignty

over "the brethren" is acknowledged, as well as His leadership in their

salvation. In Hebrews 1:6 we read, "And when He again brings the firstborn into the world, He says, `AND LET ALL THE ANGELS OF GOD WORSHIP HIM.'" Here the idea of preeminence is obvious, as all of God's

angels are instructed to worship Him, a privilege rightly reserved only

for God (Luke 4:8). The term "prototokos" is used here as a title, and

no idea of birth or origin is seen.

In both Colossians 1:18 and Revelation 1:5, Christ Jesus is called

the firstborn of the dead (or "from" the dead). These would refer especially to the leadership of Christ in bringing about the resurrection

of the dead and inauguration of a new, eternal life.

And so we are now ready to tackle the question concerning Colossians 1:15 and "firstborn of all creation." In commenting on this

passage, Kenneth Wuest said,

The Greek word implied two things, priority to all creation and

sovereignty over all creation. In the first meaning we see the absolute preexistence of the Logos. Since our Lord existed before all

created things, He must be uncreated. Since He is uncreated, He

is eternal. Since He is eternal, He is God. Since He is God, He

cannot be one of the emanations from deity of which the Gnostic

speaks.... In the second meaning we see that He is the natural

ruler, the acknowledged head of God's household.... He is Lord

of creation."'

It seems the eminent Greek scholar J. B. Lightfoot was behind at

least the outline of Wuest's comments, as he provides much the same

information in his commentary on the usage of prototokos in Colossians 1:15." He sees a definite connection between Paul's use of "firstborn" here and its appearance in the Greek Septuagint at Psalm 89:27.

He discusses both the aspects of priority to all creation as well as sovereignty over all creation. This understanding of the term is echoed by

many other scholarly sources.12

So what can we conclude? Most importantly, we see that it is simply

impossible to assume that the term "firstborn" means "first created."

Even if one were to ignore all the background information above, the

term would still not speak to creation but to birth, and such a term

could easily refer to the Son's relationship with the Father, not to any

idea of coming into existence as a creature. But when the Old Testament use of the term is examined, it primarily speaks to a position of

power, primacy, and preeminence. So how does the concept of Christ's

preeminence fit into Paul's teaching in this passage? Let's see.

ALL THINGS

Verse 16 of Colossians 1 begins, "For by Him ..." This connects

verses 16 and 17 to the thought of verse 15.13 Why is Jesus called the

"image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation"? Because,

Paul says, all things came into being by Him. We are completely missing the point if, in fact, we think verse 15 is in any way diminishing the

view of Christ being presented. Instead, Paul feels he must explain

what he means by applying such exalted titles to Christ! "Image of the

invisible God" is not a phrase to be used of a creature.14 And when we

read the phrase "firstborn of all creation," we should hear the emphasis

upon all creation. When we say that someone is the champion in a

certain sport "in all the universe," we are saying the person is the best

there is, period. So when Paul says that Jesus Christ has preeminence

over all creation, he is specifically denying that there is anything not

under His sovereign power. He then explains how that can be by asserting that all things were created by, through, and for Christ.