The Friar and the Cipher (2 page)

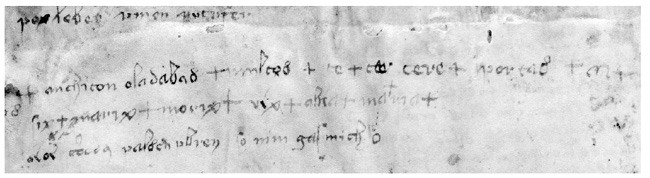

Voynich manuscript “key.” Note that characters differ from those in the body of the text.

BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

This second man, dubbed

Doctor Mirabilus

(the miraculous doctor), was an expert in mathematics, astronomy, optics, alchemy, languages, and homeopathic medicine. He had described the workings of the telescope and microscope four hundred years before Newton. He believed that the earth was spherical and that one could sail around it, an argument that was purported to have inspired Columbus two hundred years later. He believed that light moved at a distinct speed at a time when it was assumed that the movement was instantaneous. He questioned Galen, the great Roman anatomist and physician, and theorized about illness, disease, and the human body centuries before anatomy and medicine poked their heads into the modern age. He has sometimes been credited with inventing eyeglasses. He wrote of flying machines, motorized ships, horseless carriages, and submarines. He was the first man in Europe to describe in detail the formula for making gunpowder.

OUR MOST PREVALENT MENTAL IMAGE

of the thirteenth century is of knights in chain-mail hoods with red crosses on their chests, plodding on horseback through dank forests, stopping every now and then to joust with one another in a tournament on their way to Jerusalem to scuffle futilely with the infidel Muslims. It is a dreary picture, all monks and relics, serfs and saints, poverty, piety, barbarity, and ignorance.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The high Middle Ages was a time of color, romance, scheming, and intrigue. Land, power, position, and wealth were all up for grabs, and the rule of law accommodated itself to its surroundings. It was also a period of consolidation—politically, geographically, and theologically. Monarchs moved large numbers of troops from one end of Europe to the other and even into North Africa. Sea routes were open to those who could pay for a ship. Commercial travel improved as well. It has been said that the widening of roads in Europe to accommodate oxcarts after the Dark Ages was the most significant technological advance in history.

The thirteenth century was also one of the most pivotal and exciting in the history of human knowledge. Propelled by new translations of Greek classics and the work of brilliant Islamic scholars, the best minds in Christian Europe were beginning to theorize about the power of natural science. Some had even begun to question, for the first time in a millennium, whether knowledge must be restricted to the revealed word of the Bible or could instead be gained by drawing empirical hypotheses and then testing them by experiment.

After centuries of accepting official Church interpretations as to the proper exercise of Christianity, pious Christians throughout Europe had also begun to question the opulence with which popes, cardinals, bishops, and even priests lived, often among a flock that was poor, hungry, and oppressed. How could Christ have meant for disciples to live in luxury while his more humble followers starved? Thousands joined new religious movements. The thirst to throw off the controls on what to think and what to feel offered the promise of a new enlightened age. Both science and Christianity might be forever changed.

But the medieval Church had weapons of its own. On one extreme, there was sword, fire, and fear, all of which were wielded mercilessly. Many of those who raised questions were branded as heretics, rounded up, and exterminated. The Inquisition was begun in the thirteenth century as a means to institutionalize heretical repression. But there was also piety and simple decency as many in the new Orders tried to show the world the meaning of faith and true Christian values.

Yet for all that, it seemed that the ravenous need to advance knowledge, to satisfy curiosity,

to find out,

was about to overpower Christian tradition. The battle between these two forces would shape the course of Western history for the next three hundred years, and it continues to resonate today. Each side in that struggle had as its advocate a great scientific philosopher. Each was deeply pious, each believed in the total supremacy of God. One was born in England in 1214, the other in Italy a decade later. One attempted to add natural science to theology, the other to make theology a natural science. One was imprisoned, one dined with kings. One died anathemized, the other became a saint. The Italian was Thomas Aquinas, the protégé of Albertus Magnus. The Englishman was the very man who Voynich believed had authored his cipher manuscript.

Now William Romaine Newbold at the University of Pennsylvania seemed to have confirmed Voynich's guess, for the first line of the key when deciphered read:

“To me, Roger Bacon.”

FROM THE DAY THAT NEWBOLD ANNOUNCED

that he had deciphered the key, the name and reputation of Roger Bacon has been inextricably linked to the Voynich manuscript. The mystery is almost irresistible—did the brilliant medieval scientist, an expert in secret languages and codes, hounded by reactionaries in his own time, compose what is arguably the most enigmatic artifact ever uncovered? If he did write it, what does it say? Does it hide a great scientific discovery for which Bacon did not get credit? Who was he writing it for? And if he did not draft the manuscript, who did, and why is Bacon's name on it?

To make some sense of the puzzle, it is necessary to study the man as well as the manuscript. In its own way, the life of Roger Bacon is as much a cipher as the sheaf of papers Wilfrid Voynich pulled from the trunk in the Villa Mondragone. Many of the details of his life remain shadowy, and the mythology that grew up around him often blurred fact with fiction. Much of what we know has been deduced from background information rather than gleaned from irrefutable evidence.

Still, as Bacon has been a subject of almost cultish fascination for more than four centuries, a remarkable amount of scholarly detective work has been done to lift his biography from the murk. Bacon has aroused considerable passions from both those who think that he was one of the preeminent figures in the history of science, on a par with Galileo, and those who dismiss him as a quirky iconoclast whose appeal is derived from his quixotic personality rather than any real contribution to human thought. In order to objectively navigate between these extremes, a historian must rely in no small part on what Bacon's detractors are forced to admit and what his champions are forced to concede.

The manuscript's provenance is equally obscure. There are large gaps in the chain of ownership. A trail must be woven, once again not by hard data but by careful construction, the testing of relative hypotheses, the weighing of alternatives.

The scale of the investigation is breathtaking; it covers the range of human experience, skipping across time periods and disciplines. It begins with the musings of Plato and Aristotle, moves through the development of scientific and Christian thought on to the rise of universities and finally to the intellectual standoff between Roger Bacon and his belief in experiment and Thomas Aquinas and the logic of Catholicism. But Bacon's legacy and the foggy history of the manuscript also lead to spies and plots in Elizabethan England, palaces in exotic Bohemia, a spectacular showman and scientist who in his lifetime was considered a rival to Isaac Newton, and finally to modern cryptanalysis and the secret world of the premier code-breaking unit in America, the National Security Agency.

It is a journey of intellectual curiosity, moral courage, and tenacity of spirit, which is incomplete even to this day. Still, as Roger Bacon knew eight centuries ago, it is the willingness to undertake the journey, and not the results, that is so vital to human progess.

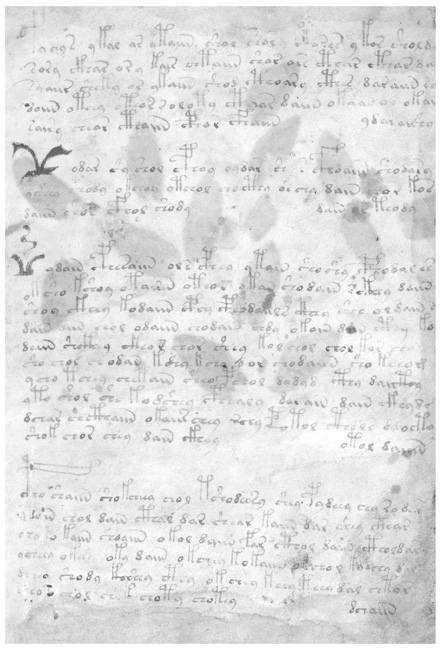

First page of the Voynich manuscript. Under ultraviolet light, the name of a previous owner and date can be seen in the margins. Under magnification, “Tepen” can just be made out.

BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

CHAPTER ONE

Turmoil and Opportunity:

Roger Bacon's England

• • •

ROGER BACON WAS BORN IN SOMERSET,

in southwest England, about one hundred miles west of London. There are no surviving records of his birth—the evidence for the date comes from Bacon himself. In a work known to have been written in 1268 he said: “I have labored much in sciences and languages, and I have up to now devoted forty years to them.” What he apparently meant by this was that he had started what today would be the equivalent of an undergraduate arts course in 1228. Since the average thirteenth-century boy started college at about fourteen, this puts the year of his birth at 1214. He lived to be eighty, so his lifetime spanned nearly the whole of the thirteenth century.

Bacon came from a family of wealthy minor nobles. His father held no title and was probably a product of the new and burgeoning merchant class, men who worked their way into higher society by accumulating cash, which was then used to purchase land and a manor house. The most successful of these could buy castles and conduct themselves as genuine nobility, knighting their sons, but Bacon's family did not seem to fall into this category. He had at least one older brother, to whom he refers in his writings, but neither was ever granted a title by the king.

Bacon remained throughout his life a product of the England of his childhood, an England in the midst of great change and rife with civil unrest that would soon erupt into full-scale war. The year after Bacon was born, the hapless King John was forced to sign Magna Carta and thus introduce the first glimmer of representative government into Europe. It was the very weakness of John and, later, his son Henry that created a vacuum into which political, social, educational, and, most significantly, scientific innovation rushed in. The most basic assumptions were challenged, the most fundamental truths rejected. So unfortunate was John as a ruler that he did not need to be known as John I, as no other king in the ensuing eight hundred years of English history was ever given the same name.

John was the fourth son of the tall, intense, mercurial Henry II, under whose lusty hand the kingdom had grown to encompass not only England but most of France—Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Touraine, Toulouse, and, with his marriage to the vivacious, wily Eleanor, the Aquitaine on the Atlantic coast. The official kingdom of France, on the other hand, was limited to Paris and its environs.

Henry's two eldest sons, Henry and Richard (called Lionheart for his military prowess) were also tall and physically imposing. John was short and unattractive. Richard still referred to John as a child when he was well into his twenties. There was a third older brother, Geoffrey, who was much cleverer than John, although this in itself was not particularly noteworthy.

With all those older sons, Henry assumed that John was never going to see the English throne, so when the boy was nineteen, he tried to get him a kingdom of his own by sending him off to conquer Ireland. John left with lots of friends, three hundred mercenaries, several barrels of silver pennies with which to pay them, and the promise of a fancy gold crown fitted out with peacock feathers when he won. In no time at all, John and his friends had spent all of the pennies on themselves, causing the mercenaries to desert. He so alienated the Irish nobility that, in a place known for internecine warfare, John managed to get all the aristocrats in Ireland to band together and agree to reject him. Richard, by contrast, had subdued the powerful rebellious barons of southern France by the age of fifteen.

Richard eventually became king (Henry and Geoffrey died young) but left almost immediately on crusade, where he was captured and held for ransom by the Holy Roman Emperor. As everyone who has ever seen

The Adventures of Robin Hood

knows, during his absence, John attempted to usurp the English throne by treachery. (In truth, it was Eleanor, not Errol Flynn, who stopped him.) When John heard that his older brother had been freed and was on his way home, he turned tail and headed for France. John was so insignificant in Richard's mind that Richard forgave him and let him come home.

Just a short time later, however, Richard died while staking out a minor castle for siege. He had disdained armor while parading around the periphery and was shot in the neck with an arrow. The boy whom his father had nicknamed “Lackland” for want of a realm was crowned King John of England at Westminster Abbey on May 25, 1199. Within five years of becoming king, he had lost most of his father's French possessions to the French king, Philip Augustus, earning him a new nickname, “Softsword,” among his own nobility.

Losing to the French turned out to be just the preliminary. In 1205, John, by virtue of an extremely dubious royal edict, found himself taking on the great Pope Innocent III. It was not really a fair fight.

INNOCENT III WAS ONE OF THE SEMINAL FIGURES

in the history of the Church. Born into an ancient aristocratic Roman family, he proved a brilliant student in both law and theology. He enjoyed a meteoric rise through the curia and was elevated to the Throne of St. Peter while still in his thirties. Innocent inherited an institution in disarray. In the century preceding his reign, the papacy had sunk to an object of ridicule, ignored by secular monarchs. One of his predecessors had been compelled to ride backward on an ass through the countryside, and another had been obliged to flee Rome disguised as a pilgrim. By a combination of force of personality and the threat of withholding sacraments, Innocent almost single-handedly turned Rome from the political nonentity that it had become into a potent pseudostate, the most important political power in Europe. “By me kings reign and princes decree justice,” he observed.

In 1205, the archbishop of Canterbury died. In Henry II's time, the English bishops would “elect” a new archbishop, although this was in fact a royal appointee. (As usual, Henry had taken custom one step further—he had not only assumed the right to elect his own man, Thomas à Becket, as archbishop, but had assumed the right to have him killed as well when Becket disagreed with him.) John naturally expected to have the same privilege as his father, but he bungled the election and Innocent claimed the right of appointment for himself. He chose the highly qualified Stephen Langton, who was at the time teaching at the University of Paris.

John was outraged at this attempt to usurp his authority and refused to let the new appointee enter the country. So began a war of wills between king and pope. Innocent placed England under interdict, which meant that English priests were forbidden to perform any of the sacraments. Suddenly, no one in England could get married, buried, or baptized. John retaliated by seizing the property of those priests who obeyed Innocent's order. To get it back, they had to swear loyalty to the crown and pay a hefty fee. They even had to pay to get their “housekeepers” (read, mistresses) back. Innocent countered by excommunicating John. The English high clergy packed up and headed to France, and by 1212 there was only one bishop left in all of England.

Still John refused to yield, so Innocent sent a message to Philip Augustus, the king of France. If Rome deposed John, the excommunicate, would Philip Augustus like to take over in his place? Philip Augustus did, in fact, want to take over England. Langton, who still had not gained entry to the country of which he was nominally the archbishop, was given letters from Innocent announcing that John had been deposed in favor of Philip Augustus. The French massed an army at the Channel.

John gave up. Langton was accepted as archbishop of Canterbury, and all of the English priests who had fled during the interdict and excommunication were restored to their property and compensated for their damages.

Philip Augustus, however, had not given up. He had not recalled his army, which was still sitting across the Channel, waiting for the order to invade. John, needing a powerful ally, turned to Innocent. To save himself, John proposed what to many in England was the unthinkable—he offered England and Ireland as fiefs of the Church, which also required that he pay a sizable monetary tribute to Rome.

France attacked anyway and was repulsed when John's subjects, to his and probably their astonishment, rallied to his aid. John, overestimating his position and their loyalty, immediately launched a counterinvasion to reclaim his father's lost territories. His armies were routed.

The English barons had had enough. A group of them took over London and forced John to put his seal to Magna Carta, or “Great Charter,” originally just a remedy for a list of baronial grievances. The key provision, however, which insisted that John obtain approval on matters of state by a board of directors composed of twenty-five of his most rebellious barons, became, albeit unintentionally, a forerunner of English representative government.

John signed under duress, but he immediately sent messengers to Innocent. Innocent, who was not the type of man to encourage the spreading of power, particularly to twenty-five men who might not do what he said, wrote a strong letter threatening to excommunicate any baron who went against the king and declaring Magna Carta “null and void of all validity forever.”

Uneasy truce then turned into civil war. The rebel barons responded by offering the crown of England to Philip Augustus's son Louis VIII in 1215. Louis came over with an army and secured London. He held the Channel and the east coast of England through the aid of a swashbuckling English pirate with the beguiling name of Eustace the Monk. By 1216, two-thirds of the English barons had come over to Louis. When Innocent died in July of that year, it seemed that John was finished.

And he was. Three months later, after losing all of his baggage, including his crown, in an ill-fated attempt to cross a river with his army, John consoled himself with “gluttonous consumption of peaches and new cider.” He caught dysentery and died, leaving the whole mess to his nine-year-old son, Henry. By the time of Henry's coronation, held in Gloucester, the rebel barons and Louis held the north and east of England, including London, Cambridge, and York, and, thanks to Eustace the Monk, all of the coastal ports in the east except Dover.

As it turned out, however, Henry's youth was his greatest asset. The sight of this lonely boy crowned in this out-of-the-way spot without the usual pomp and ceremony made Louis appear as someone taking unfair advantage of a child. The English of the south and west rallied. Henry's regents remained loyal and, in a clever move, reissued a revised Magna Carta in Henry's name, called the Charter of Liberties, thus removing the rebel barons' original grievances (and further legitimizing limited representative government). There were defections back to the crown. A battle at Lincoln, won convincingly by the royalists, siphoned off even more of Louis's support. The decisive blow came when the royal fleet sailed windward of Eustace the Monk and, in a daring maneuver, threw powdered lime into the faces of the rebel officers, incapacitating the enemy ships. The Monk's ship was boarded and he was beheaded, and it was all over. Louis sued for peace and was paid seven thousand pounds sterling to get out of England.

Until Henry III came into his majority in 1227, the government was administered by a group of experienced barons. Every now and then, especially when money was wanted for the royal treasury, the barons would have Henry reaffirm his commitment to the Charter of Liberties, and everybody got used to the idea that the barons had a say in making government policy.

No Englishman born into this period could miss the lesson of this outcome. It was possible to assail even so fundamental a principle as the divine right of kings and get away with it. With this barrier down, nothing seemed impossible.

England, separated from the mainland of Europe, provincial, uncultured, and dismissed by the more sophisticated French and Italians, could now question and test old ideas in splendid isolation. With Magna Carta upsetting the traditional political order, the country also became the perfect breeding ground for a new brand of learning, a new approach to the natural world that would spread and eventually threaten the social structure of Europe and the foundations of Christianity.

No one better embodied the character and spirit of this particularly English movement, or would surface more as both its champion and victim, than Roger Bacon. His parents had ambitions for him, an obviously gifted adolescent. In this new political climate, a talented boy, if educated properly, might advance beyond limitations of rank, perhaps even obtain employment with the king. So when he was fourteen, his parents sent him to school.

Had he lived even a half century earlier, education would have meant scriptural study at a cathedral school or monastery. But this was 1228, and a new institution had emerged, one that was exerting a great modernizing force over the whole of medieval society. Still in its infancy, it was already drawing away the best students and teachers, the most committed, the most intelligent, the most ambitious. So Roger Bacon's parents sent him off to attend one of these new institutions of learning, called a “university.”