Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (26 page)

On December 27, at 11:25 a.m., Israeli air force jets began carpet-bombing Gaza. The Israeli daily newspaper

Ha’aretz

reported that on the first day of this attack, called Operation Cast Lead, over a period of eight hours the Israeli air force dropped 100 tons of bombs on Gaza. Considering that a one-ton bomb can destroy an entire city block, and Gaza is a small place and very crowded, one can only imagine the devastation and the casualties. This was the beginning of 21 days of abject hell. Israel attacked with massive air and ground forces against an area and a population that had no military force. Israeli pilots dumped hundreds of tons of bombs, and for the people of Gaza there was nowhere to hide, no way to defend themselves and, with the border shut, nowhere to run. To make things worse, Israel claimed that notices were given to the local population that the attack was imminent and that people should leave areas that were going to be bombed. One can only imagine a mother or father sitting for days anticipating this onslaught, yet knowing full well that there was no escaping it. It was in preparation for this massive assault— apparently in response to rockets fired from Gaza into Israel—that the Gaza border had been closed.

Only hours after the bombing began, it was reported that close to 500 people were killed, including dozens of children. During our attempt to enter Gaza, I had called Suheila several times and she had constantly been encouraging me and thanking us for our efforts. After the attacks began, I wasn’t able to call her but I managed to get a few e-mail messages through. In one exchange she described how helpless she and the other doctors felt. Everything was destroyed, broken, or shattered, and there was no electricity. It was early on in the assault when she wrote to me of a six-year-old boy who was wounded and brought to the hospital. She wrote to me: “We were unable to save him.”

By the end of the 21-day attack, 1,400 people were killed, thousands wounded and maimed, and many thousands more left homeless with nowhere to turn. In an article published in

The San Diego Union-Tribune

, I wrote: “As I sit and view

the reports, photos and live videos streaming in from Gaza I find it impossible to make sense of it all.”

I recalled being taught a story from the Old Testament, where Abraham the patriarch argued with God over His decision to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorra:

And Abraham stood before the Lord. And Abraham drew near, and said: wilt thou also destroy the righteous with the wicked, perhaps there be fifty righteous within the city, wilt thou also destroy and not spare the place for the righteous that are therein?…and the Lord said, if I find in Sodom fifty just men within the city, then I will spare all the place for their sakes

. (Genesis 18:23–26)

One has to admire Abraham for his tenacity. Stepping near as he did to confront the almighty and argue with God for the sake of a principle that he held dear, the principle that human life is sacred. Abraham wanted to get a real commitment from God, that He would indeed spare the city for the lives of innocent people.

Who was there to speak for the people of Gaza? There can be no doubt that among the 1.5 million people residing in Gaza there are more than 50 righteous men and women. After all, there are 800,000 children in Gaza.

After our return, Nader and I were invited to give a talk at the University of San Diego Joan Kroc Institute of Peace and Justice. During my remarks I, mentioned that the latest assault on Gaza was not isolated but rather part of a continuous Israeli campaign against Gaza, a campaign that by that point had been going on for more than six decades. Every few years, the Israeli army found a reason to conduct a brutal attack on Gaza and leave behind as many casualties as possible, beginning as early as 1953 with the infamous Unit 101, led by Ariel Sharon. What happened shortly after our failed attempt to cross the border was a continuation of an ongoing war, a war that aims to complete the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. I heard stories of people who drove to the Gaza border to sit on lawn chairs and view the bombing.

During the lecture, members of the Zionist community who came to hear us were appalled that I would criticize Israel at such a time. “It is a question of values,” I tried to explain. “Some people believe that killing innocent civilians is morally acceptable. I think, and my Jewish roots teach me, that even if the devil himself resided in Gaza, as long as a single child resided there too, the city had to be spared.”

I felt betrayed by my own people, I felt ashamed of the country I used to be so proud of. As Nader and I flew over Egypt on our way back to Amman, I told him that I couldn’t help thinking that Gaza is a problem that is very easy to fix. “Look at the vast desert below us, nothing we can do will change it. But Gaza is not like that, in Gaza there are educated people who can work and be productive and contribute. They don’t need us to do anything but open the gates and take down the barriers.”

My people, my friends, were holding the keys to the gate and would not let anyone enter. After this trip, I started to think a little differently about what real

peace would look like. I started to think that a complete removal of all the barriers between Israelis and Palestinians was the only hope—indeed that it was inevitable.

1

Charles Glass,

The Tribes Triumphant: Return Journey to the Middle East

(London: HarperPress, 2006), 216.

Abu Ansar

1

After my experience at the Bethlehem checkpoint in April 2007, Nader and I went on to travel to Ramallah and then to Haifa to meet people in what turned out to be a marathon tour with very little time to rest. Once we were done, Nader returned to Amman, Jordan and I decided to stay in Israel/Palestine and attend the Annual Conference on Non-Violent Joint Struggle, also referred to as The Bil’in Conference. It was the second time the village Bil’in hosted a conference dedicated to the ongoing non-violent popular resistance.

I was searching for more direct forms of political activism. The wheelchair project was both important and interesting, but I realized that humanitarian work was not going to bring about a solution. Also, I was beginning to diverge from what my father and other Zionist Israeli progressives saw as the solution—that is, the two-state solution. I was beginning to see that the issues that made up the conflict could only be resolved through a state where both peoples live as equal citizens.

Obviously this was not going to happen without a fight, and the only fight to which I would dedicate myself was a non-violent one. That was why I wanted to learn more about what was happening in Bil’in. I also felt very strongly about the need to continue to defy Israel’s laws pertaining to the occupation.

I was excited that I happened to be in the country when the conference was taking place. I took a taxi from Jerusalem to Bil’in, and there were already many people there when I arrived. The event was being held under an enormous tent in the village school courtyard. As I entered the courtyard, I immediately saw Dr. Omar, Bassam Aramin, and a few other friends standing around and talking. I knew Dr. Omar through the Bereaved Families Forum. He was general director of the Palestinian health department and Nader and I met him in Ramallah during our trip with the wheelchair project. I met Bassam during a meeting of an organization called Combatants for Peace.

After we greeted one another, Dr. Omar asked me who I was with and who was going to take care of me while I was at the conference. I told him I had come alone and that I was not concerned because I was sure to meet people I knew. He

turned to a friend standing next to him and introduced him as Jamal Mansur, or Abu Ansar. He had a large body and a prominent mustache and stood about six feet and two inches.

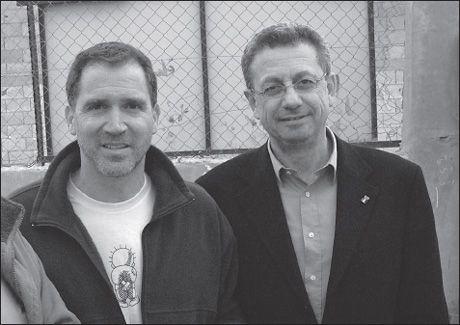

With Dr. Mustafa Barghouti in Bil’in. He was, at the time, a member of the Palestinian cabinet

.

Dr. Omar turned to me. “I have to go, but he will take care of you, he is our good friend from prison.”

Then he took my arm, turned to Jamal, pointed to me, and said in Arabic,

“Hadha hahibi, hahibi, habibi!”

In other words, I was a special guy and a close friend. Jamal had a house in the village and was staying there for the entire conference. He spoke excellent Hebrew, and he took good care of me, making sure I was comfortable at all times. I found him to be a warm-hearted, well-mannered gentleman. He introduced me to all the dignitaries at the conference, and indeed there were many. He took me to meet Fadwa Barghouti, the wife of the famous imprisoned Palestinian leader Marwan Barghouti. We sat with her for a while and talked.

I said, “I hope your husband will be released soon, his country and his people need him.”

“I hope he is released too, but for his family and his children, who need him too.”

Then, Dr. Mustafa Barghouti

2

arrived. At the time, he was a member of the

Palestinian cabinet. As dignitaries came and went, people would form lines to walk up and say hello. I couldn’t help noticing that every time Jamal walked up to greet some dignitary, people would step aside and allow him to go first.

Jamal has large hands and he uses them affectionately, placing them on people’s shoulders or knees when he speaks. We sat in the back of the huge tent and divided our time between listening to the various speakers and just chatting with each other. I understood that Jamal and Bassam and Dr. Omar all knew one another from the time they had spent in Israeli prisons, but I never knew what the charges had been against them. As we talked throughout the day, the complex world of Palestinian prisoners—a world I knew nothing about—began to unfold.

“Abu Ansar, why were you imprisoned?” I asked at one point.

“Please call me Jamal. Well, we were young and foolish and we did stupid things. It doesn’t matter now.”

I decided to let it go for a while. When Jamal would introduce me to people, each time he said the same thing: “He is the son of General Matti Peled, the Israeli general who met Yasser Arafat in Tunis. His sister’s daughter was killed in an attack in ’97.”

Israeli and Palestinian societies are similar in many ways, but in one way they are virtually identical. In both societies, there are two groups of people who are holy-like, untouchable: the warriors and the bereaved. Those who fought for the cause and those who sacrificed loved ones. Whenever I give a lecture or write about

the Israeli/Palestinian issue, I am always introduced as the son of General Peled and the uncle of Smadar Elhanan; it is as though these two aspects of my personal story give me the right to speak.

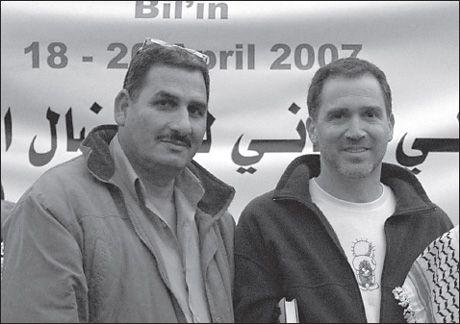

Jamal Mansur, or Abu Ansar, and I at the Annual Conference on Non-Violent Joint Struggle in Bil’in

.

Jamal’s introduction usually brought a response along the lines of: “Of course I remember General Peled, Abu Salaam. He helped me so much when the Israeli authorities wanted to deport me.” I heard that sort of thing being said over and over throughout the day by so many people, and I still hear it each time I meet Palestinians in the West Bank.

Then Jamal would also add, “He and his Palestinian partner Mr. Elbanna just completed a project to bring 1,000 wheelchairs, 500 to Israelis and 500 to Palestinians.”

When lunch was served Jamal took me to sit with his friends. After lunch we helped ourselves to coffee and then we went to sit by ourselves again.

“Jamal, why were you in prison?” I asked once more.

“I was young and foolish; I was 16 years old. One day, Israeli soldiers came to our village, Bil’in, where I grew up and imposed a curfew. The curfew meant no one could leave the house. It was a hot day and my little sister was thirsty and my mother wanted to step out to fetch clean water, but the soldiers wouldn’t let her. Each time she tried they just said no. The day progressed, and with it the heat. There was a bucket near the house with water that was used to wash vegetables. The water was dirty with soil and shrubs. The soldier pointed to it and said, ‘Here, she can drink this.’“ Jamal paused for a moment. “She was just a little girl who was thirsty, how do you say no to something like that?

“So my mother took the water and tried to strain it through a cloth and give it to the little girl. But she cried because she could not drink the dirty water. I couldn’t just sit and watch this sort of thing. Then I decided I have to join the resistance to fight.”

“So what happened that you were arrested?” I pressed him. He was clearly reluctant to tell me what happened, but a bond was beginning to form between us, one that would become stronger over the years.

“One night I was told we had an operation. Three other members of the cell and I were sent on a mission. It was to kill two armed Israeli soldiers who were guarding a branch of an Israeli bank in Ramallah.” As I listened to the story, I couldn’t help wondering why these soldiers were guarding a bank in the first place. My guess was that they were young and inexperienced and were carelessly placed in this predicament by their superiors much like I had been so many times during my service. Jamal, with three others, snuck up and killed the two soldiers.

“How did you kill them?”

“Two of us took one soldier, and two took the other soldier, and we stabbed them to death with a knife.”

My entire childhood and much of my adult life I loved and admired the IDF. I used to say that I could recite the army ranks before I knew my alphabet. Now I

was hearing about two soldiers, two young men wearing the uniform I respected so much, being stabbed to death. How did I feel about it? I was saddened that two young men lost their lives, and I was saddened that a good man was brought to a point where he chose to take a life. But I felt no special affinity to these soldiers because they were Israeli or because they were IDF soldiers: The state that they served had abused its power and for that abuse, these soldiers had to pay with their lives.

In the end, two soldiers were dead, the young men who killed them spent years in prison, and all of this benefited no one. It advanced no cause and it improved the lives of not one person. Surely humanity was capable of more than this.

After carrying out the attack, Jamal lay low for a while. He went back to work in Tel Aviv, and six months later he was caught.

“At first they tied me up so that I was completely bent over,” he recounted to me. “They gagged me and took me to a remote spot by the beach in Tel Aviv. They beat me for hours under the cover of darkness. It was so bad that I prayed they would just throw me into the sea and let me drown.” Jamal has nerve damage in his back and legs from the beating. In his youth, he had been an athlete and had practiced karate. Today, he can do nothing but walk, and he doesn’t walk very fast.

He continued: “Then the Israeli authorities blew up my father’s house.” Jamal was sentenced to life in prison, but was released in 1985 as part of the Ahmed Jibril prisoner exchange: 1,150 Palestinian prisoners were released from Israeli prisons in exchange for three Israeli soldiers who were held by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in Lebanon.

Upon his release, as the prisoners were leaving the bus, Jamal was called by one of the Israeli officers and was immediately placed under administrative arrest. This meant imprisonment without charge or trial. He was put back on the bus and sent to jail for six more months. They did this to him twice, adding a year to his jail time. “I told my wife not to wait for me and not to expect me to return,” he said. “If I come back she will know when I arrive. Otherwise the disappointment is to hard to bear.”

During his years in prison, Jamal developed a reputation as a man of character, a man that could be trusted. Both the prison guards and the prisoners trusted him and he often acted as liaison and peacemaker.

Jamal and I have been friends ever since that day in Bil’in. He’s been instrumental in helping me travel throughout the West Bank, and over the years he has introduced me to many excellent people I otherwise would not have met. We would walk through Ramallah and stop at a shop or an office or a corner neighborhood store. He would gesture toward a fellow and say, “We were in prison together.” After which, he would introduce me to his friend. Then we’d all sit and

have coffee or juice, and I never felt more comfortable and welcome than I did in these random meeting with Palestinians who had fought and paid dearly for the sake of freedom. Most of them moved on with their lives after prison but didn’t lose their desire to see better days. They managed to create the semblance of normalcy in this cramped and confined existence Israel permitted them. We would spend half an hour or so before going to the next place to meet another friend.