The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ (20 page)

Read The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ Online

Authors: David Shenk

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

The lesson is clear: when we celebrate a great achievement, we are not just celebrating hard work, but also a competitive process where some have won and others have lost. This would be a brutal feature of humanity if we didn’t also know—from

chapter 3

—that given the right mind-set, failure is good for us.

The problem is that different people have very different attitudes toward competition. In 1938, Harvard psychologist Henry A. Murray proposed that human beings could be separated into two distinct competitive personalities: HAMs (“high in achievement motivation”) and LAMs (“low in achievement motivation”). HAMs enjoy and perform better under directly competitive conditions than they do under noncompetitive conditions. LAMs dislike competition, do not seek it out, and are less happy and productive when pushed into it. They do better when pursuing so-called mastery goals—improvement of a skill in comparison to oneself rather than to others.

In Western societies, a higher proportion of men are HAMs and a higher proportion of women are LAMs. Interestingly, though, it turns out that this gender divide is not universal or genetically hardwired.

In 2006, economists Uri Gneezy, Kenneth L

. Leonard, and John A. List compared competitive instincts in two very different societies: Maasai in Tanzania and Khasi in India. Among the patriarchal Maasai, men choose to compete at twice the rate of women. But among the Khasi, which is rooted in a matrilineal culture where women inherit property and children are named from the mother’s side of the family, women choose to compete much more often than men.

The first point to take away from this study is that there is clearly no fixed male or female competitive biology. How men and women act is dependent on cultural circumstances and gene-environment interaction. “Our results have import within the policy community,” Gneezy and colleagues concluded. “If the difference is based on nurture, or an

interaction between nature and nurture

… public policy might [best] be targeting the socialization and education at early ages as well as later in life to eliminate this asymmetric treatment of men and women.”

The much larger point is that a person’s internal motivation is highly malleable and is closely tied to social reality. Our cultural landscape directly affects whether and how people challenge themselves and others to achieve.

The trick, then, is to sculpt a culture that encourages healthy achievement and that can accommodate different personality types and levels of motivation. How can we best create classrooms, offices, and communities where competitive instincts are rewarded but where less competitive individuals also feel energized rather than suffocated?

Not surprisingly, the answer turns out to be making sure that near-term tasks are clear and meaningful.

If short-term tasks can be made relevant to long-term goals, researchers have found, then even LAMs will dive in and relish the challenge

. This fits perfectly with Ericsson’s “deliberate practice”—the satisfaction of working hard to master near-term goals, learning to enjoy the process rather than focus on the large gulf between current abilities and the far-off ideal.

It also points clearly to a new direction for schools, which must recognize that abilities are achievable skills and not innate entities (à la Carol Dweck,

chapter 5

) and must find a way to motivate every child.

Sound too ambitious? Toronto writer and educator John Mighton might have agreed before he became a math tutor in his late twenties. But after a short time working with so-called learning-impaired students, Mighton was shocked to learn how far and fast they could progress with the right teaching methods. He realized that countless numbers of math students get left behind at one point or another simply because they can’t quite grasp one small concept; they then quickly lose confidence in their ability to go forward, and their abilities stagnate.

Mighton’s response to this problem was to break down math concepts into the most easily digestible form and help students build skills and confidence in tandem

. He called his new program “Junior Undiscovered Math Prodigies,” or JUMP.

“With proper teaching and minimal tutorial support

,” he writes in his book

The Myth of Ability

, “a Grade 3 class could easily reach a Grade 6 or 7 level in all areas of the mathematics curriculum without a single student being left behind. Imagine how far children might go (and how much they might enjoy learning) if they were offered this kind of support throughout their school years.”

Mighton does not claim his particular teaching method as the only approach, or even the best

. But “whatever method is used,” he insists, “the teacher should never assume that a student who initially fails to understand an explanation is therefore incapable of progressing.”

We know—thanks to Carol Dweck, Robert Sternberg, James Flynn, and others—that Mighton is absolutely correct.

In fact, countless students fall behind in math and other subjects for exactly the same reason others generally hate to compete directly in any field

: it makes them feel that their permanent limitations are being exposed. People stop striving in a certain area when they receive the message that they simply don’t have what it takes.

“I wasn’t quite suited for the educational system,” Bruce Springsteen has said

of his early days. “One problem with the way the educational system is set up is that it only recognizes a certain type of intelligence, and it’s incredibly restrictive—very, very restrictive. There’s so many types of intelligence, and people who would be at their best outside of that structure [get lost].”

Schools can adapt to the reality that different people have different ways of learning. It is not a contradiction to maintain high expectations of every student

and

to show compassion and creativity for those who, inevitably, do not immediately meet those expectations. Failure should be seen as a learning opportunity rather than a revelation of students’ innate limits.

“If non-linear leaps in intelligence and ability are possible

,” writes John Mighton, “why haven’t these effects been observed in our schools? I believe the answer lies in the profound inertia of human thought: when an entire society believes something is impossible, it suppresses, by its very way of life, the evidence that would contradict that belief.”

Set high expectations, but also show compassion, creativity, and patience

. This same set of principles applies to other sectors of society and culture. It’s how the government should treat its poorest citizens and how the legal system should treat its transgressors. It’s how bosses should treat employees and how businesses should treat consumers. It’s how the media should treat its audience.

There is a much uglier alternative. We can instead embrace a rawer, purer competitive atmosphere—a winner-take-all system.

“Man—every man—is an end in himself, not the means to the ends of others,” Ayn Rand wrote

in 1962. “He must exist for his own sake … The pursuit of his own rational self-interest and of his own happiness is the highest moral purpose of his life.” This is the laissez-faire ideal, the belief that pure self-interest and market efficiencies will create the most productive society.

A laissez-faire society

will

bring great achievement. The most competitive will rise to the top, at the expense of others. Competition will know no moral boundary. Society will, in every way, become more and more extreme, producing some great achievers and many unfortunate losers. Recall

Sports Illustrated

’s Alexander Wolff’s analysis of the Kenyan running culture: with a million Kenyan schoolboys running so enthusiastically,

Kenyan coaches can afford to push their athletes to the most extreme boundaries

, knowing that they will lose many to exhaustion and injury, but that enough will thrive to make their teams successful.

But this sacrificial ethos is not the sort of humanity we seek. Instead, we embrace the agonistic ideal: healthy rivalry, high expectations, respect and compassion for all.

The genius in all of us is that we can all rise together.

Join other readers in online discussion of this chapter: go to

http://GeniusTalkCh9.davidshenk.com

CHAPTER TEN

Genes 2.1—How to Improve Your Genes

We have long understood that lifestyle cannot alter heredity. But it turns out that it can …

Over the last century, few scientists’ names have been subjected to as much historical derision as early-nineteenth-century French biologist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck.

In textbooks and elsewhere, Lamarckism has been defined (and mocked) as a crude, pre-Darwinian conception of evolution, tainted by the flimsy idea that biological heredity can somehow be altered through personal experience

.

Lamarck called it “the inheritance of acquired characteristics”—the notion that an individual’s actions can alter the biological inheritance passed on to his or her children

.

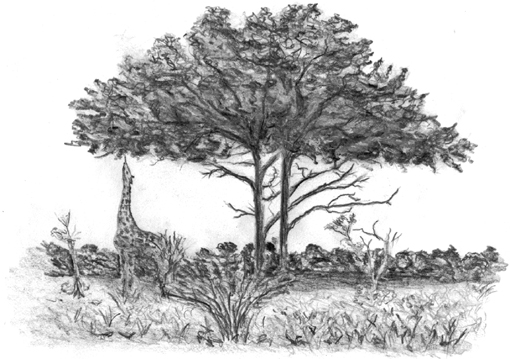

For example, giraffes, according to Lamarck’s theory, had developed longer and longer necks over the generations because of the giraffe’s practice of reaching higher and higher for food

.

The giraffe is

… obliged to browse on the leaves of trees and to make constant efforts to reach them. From this habit long maintained in all its race, it has resulted that the animal’s forelegs have become longer than its hind-legs, and that its neck is lengthened.

—Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck,

Philosophie Zoologique

, 1809

Courtesy of Craig Holdrege

This sounds preposterous to us now, mostly because it is so different from our Darwinian understanding of evolution.

After Darwin’s

Origin of Species

and others’ subsequent discovery of genes, a very different notion—the theory of natural selection—became scientific and popular consensus

. For more than a century, it has been universally accepted that genes are altered not by individual experience but by random mutation and other factors. The individuals whose mutations happen to best fit their environments will thrive and will pass their genes on to future generations.

We cannot change our genes

. In the 1950s, the discovery of DNA reaffirmed this idea and secured Lamarck’s place in history as the intellectual loser. Today, any high school student knows that genes are passed on unchanged from parent to child, and to the next generation and the next. Lifestyle

cannot

alter heredity.

Except now it turns out that it can …

. . .

In 1999, botanist Enrico Coen and his colleagues at the United Kingdom’s John Innes Centre were trying to isolate the genetic differences between two distinct types of the toadflax plant. The newer and rarer type, named “Peloria” (below) by Carl Linnaeus in the mid-eighteenth century, has a distinct type of flower with five spurs surrounding it like a star.