The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ (5 page)

Read The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ Online

Authors: David Shenk

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

Genes, proteins, and environmental signals (including human behavior and emotion) constantly interact with one another, and this interactive process influences the production of proteins, which then guide the functions of cells, which form traits.

Note the influence-arrows moving in both directions in the second sequence. “Biologists have come to realise that if one changes

either

the genes

or

the environment, the resulting behaviour can be dramatically different,” explains City University of New York evolutionary ecologist Massimo Pigliucci. “The trick, then, is not in partitioning causes between nature and nurture, but in [examining]

the way genes and environments interact dialectically to generate an organism’s appearance and behaviour

.”

The great irony, then, of our endless efforts to distinguish nature from nurture is that we instead need to do exactly the opposite: to try to understand precisely how nature and nurture

interact

. Precisely which genes do get switched on, and when, and how often, and in what order, will make all the difference in the function of each cell—and the traits of the organism.

“In each case,” explains Patrick Bateson,

“the individual animal starts its life with the capacity to develop in a number of distinctly different ways

. Like a jukebox, the individual has the potential to play a number of different developmental tunes. But during the course of its life it plays only one tune. The particular developmental tune it does play is selected by [the environment] in which the individual is growing up.”

From that first moment of conception, then, our temperament, intelligence, and talent are subject to the developmental process. Genes do not, on their own, make us smart, dumb, sassy, polite, depressed, joyful, musical, tone-deaf, athletic, clumsy, literary, or incurious. Those characteristics come from a complex interplay within a dynamic system. Every day in every way you are helping to shape which genes become active.

Your life is interacting with your genes

.

The dynamic model of GxE turns out to play a critical role in everything—your mood, your character, your health, your lifestyle, your social and work life. It’s how we think, what we eat, whom we marry, how we sleep. The catchy phrase “nature/nurture” sounded good a century ago, but it makes no sense today, since there are no truly separate effects. Genes and the environment are as inseparable and inextricable as letters in a word or parts in a car. We cannot embrace or even understand the new world of talent and intelligence without first integrating this idea into our language and thinking.

We need to replace “nature/nurture” with “dynamic development.”

How did Tiger Woods end up with the most dependable stroke and the toughest competitive drive in the history of golf? Dynamic development. How did Leonardo da Vinci develop into an unparalleled artist, engineer, inventor, anatomist, and botanist? Dynamic development. How did Richard Feynman advance from a boy with a merely good IQ score to one of the most important thinkers of the twentieth century? Dynamic development.

Dynamic development is the new paradigm for talent, lifestyle, and well-being. It is how genes influence everything but strictly determine very little. It forces us to rethink everything about ourselves, where we come from, and where we can go. It promises that while we’ll never have true control over our lives, we do have the power to impact them enormously. Dynamic development is why human biology is a jukebox with many potential tunes—not specific built-in instructions for a certain kind of life, but built-in capacity for a variety of possible lives. No one is genetically doomed to mediocrity.

Dynamic development was one of the big ideas of the twentieth century, and remains so

. Once our brand-new parents in University Hospital understand its implications for their newborn girl, it will affect how they live, how they parent, and even how they vote.

1

Estimates of the actual number of genes vary

.

Join other readers in online discussion of this chapter: go to

http://GeniusTalkCh1.davidshenk.com

CHAPTER TWO

Intelligence Is a Process, Not a Thing

Intelligence is not an innate aptitude, hardwired at conception or in the womb, but a collection of developing skills driven by the interaction between genes and environment. No one is born with a predetermined amount of intelligence. Intelligence (and IQ scores) can be improved. Few adults come close to their true intellectual potential.

[Some] assert that an individual’s intelligence is a fixed quantity

which cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism.

—Alfred Binet,

inventor of the original IQ test, 1909

L

ondon is a taxi driver’s nightmare, a preposterously large and convoluted urban jungle built up chaotically over some fifteen hundred years. This is not a city built neatly on a grid, like Manhattan or Barcelona, but a crude patchwork of ancient Roman, Viking, Saxon, Norman, Danish, and English settlement roads, all laid on top of and around one another. Within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross Station, some twenty-five thousand streets connect and bisect at every possible angle, dead-ending into parks, monuments, shops, and private homes. In order to be properly licensed, London taxi drivers must learn

all

of these driving nooks and crannies—an encyclopedic awareness known proudly in the trade as “The Knowledge.”

The good news is that, once learned, The Knowledge becomes literally embedded in the taxi driver’s brain

. That’s what British neurologist Eleanor Maguire discovered in 1999 when she and her colleagues conducted MRI scans on London cabbies and compared them with the brain scans of others. In contrast with noncabbies, experienced taxi drivers had a greatly enlarged posterior hippocampus—that part of the brain that specializes in recalling spatial representations. On its own, that finding proved nothing; theoretically, people born with larger posterior hippocampi could have innately better spatial skills and therefore be more likely to become cabbies. What made Maguire’s study so striking is that she then correlated the size of the posterior hippocampi directly with each driver’s experience: the longer the driving career, the larger the posterior hippocampus. That strongly suggested that spatial tasks were actively changing cabbies’ brains. “These data,” concluded Maguire dramatically, “suggest that the changes in hippocampal gray matter … are acquired.”

Further, her conclusion was perfectly consistent with what others have discovered in recent studies of violinists, Braille readers, meditation practitioners, and recovering stroke victims

: that specific parts of the brain adapt and organize themselves in response to specific experience. “The cortex has a remarkable capacity for remodeling after environmental change,” reported Harvard psychiatrist Leon Eisenberg in a comprehensive review.

This is our famous “plasticity

”: every human brain’s built-in capacity to become, over time, what we demand of it. Plasticity does not mean that we’re all born with the exact same potential. Of course we are not. But it does guarantee that no ability is fixed. And as it turns out, plasticity makes it virtually impossible to determine any individual’s true intellectual limitations, at any age.

How smart can you become? What are you capable of intellectually? For many decades, psychologists thought they had a reliable instrument to answer this question: the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, otherwise known as the IQ test. This combination of tests, measuring language and memory skills, visual-spatial abilities, fine motor coordination, and perceptual skills, was said by its inventor, Lewis Terman, to reveal a person’s “original endowment”—his innate intelligence.

Psychological methods of measuring intelligence

[have] furnished conclusive proof that native differences in endowment are a universal phenomenon.

—Lewis Terman,

Genetic Studies of Genius

, 1925

A prominent research psychologist at Stanford University,

Terman was part of a well-established movement convinced that intelligence was an inborn asset, inherited through genes, fixed at birth, and stable throughout life

. Revealing each person’s intelligence would, they believed, help individuals find their rightful places in society and help society run more efficiently. The movement’s original founder had been Francis Galton, a half cousin to, and peer of, Charles Darwin in mid-nineteenth-century England.

After Darwin published

On the Origin of Species

in 1859, Galton immediately sought to further define natural selection

by arguing that differences in human intellect were strictly a matter of biological heredity—what he called the “hereditary transmission of physical gifts.”

Galton did not share the cautious scientific temperament of his cousin Darwin but was a forceful advocate for what he believed in his gut to be true.

In 1869, he published

Hereditary Genius

, arguing that smart, successful people were simply “gifted” with a superior biology

.

In 1874, he introduced the phrase “nature and nurture” (as a rhetorical device to favor nature)

.

In 1883, he invented “eugenics,” his plan to maximize the breeding of biologically superior humans and minimize the breeding of biologically inferior humans

. All of this was in service to his conviction that natural selection was driven exclusively by biological heredity and that the environment was just a passive bystander. In fact, it was actually Galton, not Darwin, who laid the conceptual groundwork for genetic determinism.

A few decades later, though, Galton’s followers ran into a serious problem: they couldn’t actually locate the natural, innate intelligence they were arguing for. In fact, they couldn’t even agree how to define it. Was intelligence a facility in logical reasoning? Spatial visualization? Mathematical abstraction? Physical coordination? “In truth,” lamented British psychologist and statistician Charles Spearman,

“[the word] ‘intelligence’ has become a mere vocal sound

, a word with so many meanings that finally it has none.”

In 1904, Spearman introduced his own solution to this problem:

there must be a single “general intelligence” (

g

for short)

, he theorized, a centralized entity of intellectual skills. And though it couldn’t be measured directly—and still can’t—Spearman argued that

g

could be detected statistically, through a correlation of different measures. Using his “simple” mathematical formula

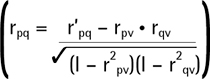

he established a correlation between school marks, teachers’ subjective assessments, and peers’ assessments of “common sense.” This correlation, Spearman argued, proved the existence of a central, inborn thinking ability.

“

G

is, in the normal course of events, determined innately,” Spearman declared

. “A person can no more be trained to have it in higher degree than he can be trained to be taller.”