The Ghost in the Machine (22 page)

stay, and became a cornerstone of modern evolutionary theory. Animals

and plants are made out of homologous organelles like the mitochondria,

homologous organs like gills and lungs, homologous limbs such as arms and

wings. They are the stable holons in the evolutionary flux.

The phenomena

of homology implied in fact the hierarchic principle in phylogeny as

well as in ontogeny.

But the point was never made explicit, and the

principles of hierarchic order hardly received a cursory glance. This

may be the reason why the inherent contradictions of the orthodox theory

could pass so long unnoticed.

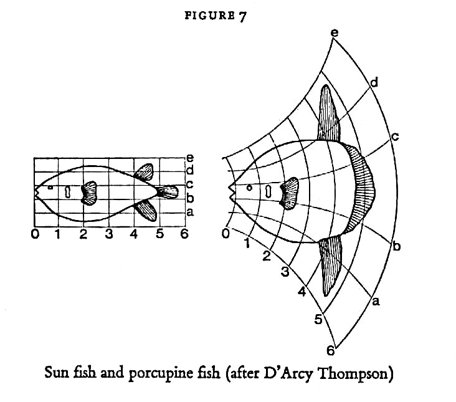

the stability of evolutionary holons. Such are the geometrical relations

discovered by d'Arcy Thompson, which demonstrate that one species may

become transformed into another and yet preserve its own basic design. The

drawings below show a porcupine fish (Diodon) and the very different

looking sun fish (Orthogoriscus) as they appear in Thompson's classic,

On Growth and Form

, published in 1917.

motor-car manufacturers when they bring out a new model, which differs

from the previous one merely in some modifications of this or that

component, while the other standardised parts remain unaltered. In the

case of the fish, it is not a particular organ that has been modified,

but the chassis and body-line as a whole. Yet it has not been arbitrarily

re-designed. The pattern has remained the same. It has merely been evenly

distorted according to a simple mathematical equation. Imagine the drawing

of the porcupine fish and its lattice of Cartesian co-ordinates imprinted

on a rubber sheet. The sheet is thicker at the head end, and therefore

more resistant than at the tail end. Now you grip the top and bottom

edges of the rubber sheet and stretch it. The result will be the sun

fish. Corresponding points of the anatomy of the two fishes will have

the same co-ordinates (the eye, for instance, will have 'longitude' 0,5,

and 'latitude' C).

the outline drawing of an animal on a grid of co-ordinates, and then

drawing another animal belonging to the same zoological group, he found

that he could transform one shape into the other by some simple trick

of rubber-sheet-geometry, which can be expressed by a mathematical

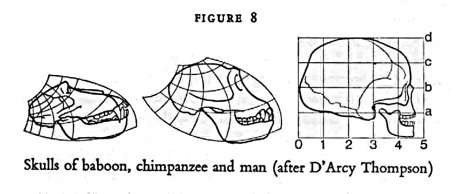

formula. The next drawing, Figure 8, shows the transformation, by means

of a harmoniously deformed grid of Cartesian co-ordinates, of a baboon's

skull into a chimpanzee's and a man's.

into the evolutionary workshop. Here are d'Arcy Thompson's own comments:

We know beforehand that the main difference between the human

and the Simian types depends upon the enlargement or expansion of

the brain and brain case in man, and the relative diminution or

enfeeblement of his jaws. Together with these changes, the facial

angle increases from an oblique angle to nearly a right angle in

man, and the configuration of every constituent bone of the face

and skull undergoes an alteration. We do not know to begin with,

and we are not shewn by the ordinary methods of comparison, how

far these various changes form part of one harmonious and congruent

transformation, or whether we are to look, for instance, upon the

changes undergone by the frontal, the occipital, the maxilliary and

the mandibular regions as a congeries of separate modifications or

independent variables. But as soon as we have marked out a number

of points in the gorilla's or chimpanzee's skull, corresponding with

those which our co-ordinate network intersected in the human skull,

we find that these corresponding points may be at once linked up by

smoothly curved lines of intersection, which form a new system of

co-ordinates and constitute a simple 'projection'* of our human skull

. . . and in short it becomes at once manifest that the modifications

of jaws, brain-case, and the regions between, are all portions of

one continuous and integral process. [10]

* In the sense of Projective Geometry.

changes 'in all and every direction'. If that were the case we should

get what Thompson calls 'a congeries of separate modifications or

independent variables'. In fact, the variations are inter-dependent,

and must be controlled from the apex of the hierarchy which co-ordinates

the pattern of the whole by harmonising the relative growth-rates of

the various parts.

appropriate changes in the other parts of the skull, effected by a

simple and elegant geometrical tramformation. The eighteenth century was

familiar with this kind of phenomenon, which the twentieth took a long

time to re-discover. Goethe called it 'Nature's budgeting law', Geoffroy

St. Hilaire called it

loi du balancement

, the principle of the

equilibrium of organs. From the concept of developmental homeostasis there

is only one logical step to the concept of evolutionary homeostasis --

the

loi du balancement

applied to phylogenetic changes. Faithful to

Goethe, one might call it the preservation of certain basic, archetypal

designs through all changes, combined with the striving towards their

optimal realisation in response to adaptive pressures.

in a puzzle. The enigma concerns the marsupials -- the class of pouched

animals living in Australia. The puzzle is that evolutionists refuse to

see the enigma.

refers to the near-extinct monotremes, such as the duck-billed platypus,

a kind of living fossil which lays eggs as reptiles do, but suckles its

young.) The marsupials could be called the poor relatives of us 'normal',

that is, placental, mammals; they have evolved along a parallel branch of

the evolutionary tree. The marsupial embryo, while in the womb, receives

hardly any nourishment from its mother. It is born in a very immature

state of development, and is reared in an elastic pouch, or bag of skin,

on the mother's belly. A newborn kangaroo is really a half-finished job

-- about an inch long, naked, blind, with hind-legs that are no more

than embryonic buds. One might speculate whether the human infant, more

developed but still helpless at birth, would be better off in a maternal

pouch than in a cot; and also whether this would increase its oedipal

inclinations. But whether the marsupial's method of reproduction is better

or worse than the placental's, the point is that it is fundamentally

different.

in the Age of Reptiles, and have evolved separately, out of some

small mouse-like common ancestral creature, over some hundred and

fifty million years. The enigma is, why so many species produced by

the independent evolutionary line of the marsupials are so startlingly

similar to placentaIs. It is almost as if two artists who had never met,

never heard of each other, and never had the same model, had painted

a parallel series of nearly identical portraits. Figure 9 shows on the

left side a series of placental mammals, and on the right their opposite

numbers among marsupials.

A. Marsupial jerboa and placental jerboa.

B. Marsupial flying phalanger and placental flying squirrel (after Hardy).

C. Skull of marsupial Tasmanian wolf compared to skull of placental wolf

(after Hardy).

of animals have evolved independently from each other. Australia was

cut off from the Asiatic mainland some time during the late Cretaceous,

when the only existing mammals were unpromising-looking tiny creatures,

hanging precariously on to existence. The marsupials seem to have evolved

earlier than the placentaIs from a common egg-laying ancestor with

part-reptilian, part-mammalian features; at any rate, the marsupials got

to Australia before it was cut off, and the placentals did not. These

immigrants were, as already said, mouse-like creatures, probably not

unlike the still surviving, yellow-footed pouched mouse, but much more

primitive. And yet these mice, confined to their island continent,

branched out and gave rise to pouched versions of moles, ant-eaters,

flying squirrels, cats and wolves -- each like a somewhat clumsy copy

of the corresponding placentals.* Why, if evolution were a free-for-all,

restrained only by selection for fitness, why did Australia not produce

some of the bug-eyed monsters of science fiction? The only moderately

unorthodox creation of that isolated island in a hundred million years

are the kangaroos and wallabies; the rest of its fauna consists of

rather poor replicas of more efficient placental types -- variations on

a limited number of archetypal themes. **

* Marsupials have also evolved, again independently, in South America.

** The reasons for the inferiority of marsupials compared to

placentals will be discussed in Chapter XVI.

theory is summed up in the following passage from an otherwise excellent

textbook, that I have repeatedly quoted: 'Tasmanian [i.e., marsupial]

and true wolves are both running predators, preying on other animals of

about the same size and habits. Adaptive similarity [i.e., adaptation

to similar environments] involves similarity also of structure and

function. The mechanism of such evolution is natural selection.' [11]

And G.G. Simpson, a leading Harvard authority, discussing the same

problem, concludes that the explanation is 'selection of random

mutations'. [12]

deus ex machina

. Are we really to believe that

the condition described by the vague terms 'preying on animals of

approximately the same size and habits' -- which could be applied to

hundreds of different species -- sufficiently explains the emergence,

twice over, independently from each other, of the almost identical two

skulls in Figure 9? One might as well say, with the wisdom of hindsight,

that there is only one way of making a wolf, which is to make it look

like a wolf.

Chapter VI

, I compared the series of scanning

and filtering mechanisms through which the intake of our sense-organs must

pass before it is admitted to awareness and found worthy to be preserved

by memory, to the seventeen gates of the Kremlin. The sense-receptors

of eye, ear and skin are exposed (in a famous phrase of William James')

to a continuous bombardment by the 'blooming, buzzing confusion' of

the outside world; without careful scrutiny by the sentries guarding

the gates, we should be at the mercy of all random intruders, and our

minds and memories would be all confusion, unable to make sense of our

chaotic sensations.

Other books

The Black Widow by John J. McLaglen

Plaster and Poison by Jennie Bentley

Moonlight & Vines by Charles de Lint

MJ by Steve Knopper

Guardian Bears: Marcus by Leslie Chase

In God's Name by David Yallop

Chessmen of Doom by John Bellairs

Secrets of the Hollywood Girls Club by Maggie Marr

The Forest Lord by Krinard, Susan

All over Again by Lynette Ferreira