The Gift of Rain

Tan Twan Eng

Hachette

Copyright © 2008 Tan Twan Eng

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the Publisher.

Printed in the United States of America. For information address Weinstein Books, 22 Cortlandt Street, New York, NY 10007.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

ISBN: 978-1-602-86059-9

First eBook Edition: May 2008

Contents

BOOK ONE

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

BOOK TWO

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

For my parents, En vir Regter AJ Buys wat my geleer het hoe om te lewe.

“I am fading away. Slowly but surely. Like the sailor who watches his home shore gradually disappear, I watch my past recede. My old life still burns within me, but more and more of it is reduced to the ashes of memory.”

The Diving Bell & theutterfly,

Jean-Dominique Bauby

BOOK ONE

Chapter One

I was born with the gift of rain, an ancient soothsayer in an even more ancient temple once told me.

This was back in a time when I did not believe in fortunetellers, when the world was not yet filled with wonder and mystery. I cannot recall her appearance now, the woman who read my face and touched the lines on my palms. She said what she was put into this world to say, to those for whom her prophecies were meant, and then, like every one of us, she left.

I know her words had truth in them, for it always seemed to be raining in my youth. There were days of cloudless skies and unforgiving heat, but the one impression that remains now is of rain, falling from a bank of low-floating clouds, smearing the landscape into a Chinese brush painting. Sometimes it rained so often I wondered why the colors around me never faded, were never washed away, leaving the world in moldy hues.

* * *

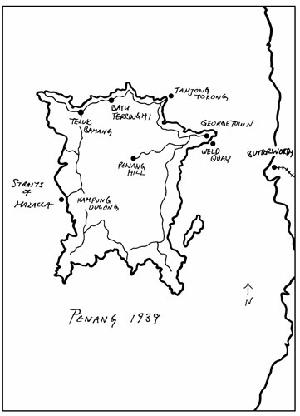

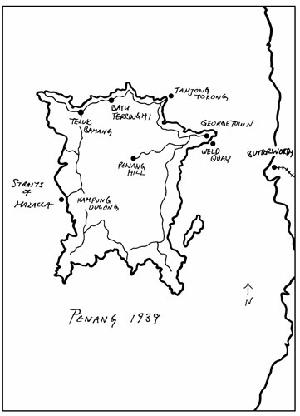

The day I met Michiko Murakami, too, a tender rain had dampened the world. It had been falling for the past week and I knew more would come with the monsoon. Already the usual roads in Penang had begun to flood, the sea turning to a sullen gray.

On this one evening the rain had momentarily lessened to an almost undetectable mist, as though preparing for her arrival. The light was fading and the scent of wet grass wove through the air like threads entwining with the perfume of the flowers, creating an intricate tapestry of fragrance. I was out on the terrace, alone as I had been for many years, on the edge of sleep, dreaming of another life. The door chimes echoed through the house, hesitant, unfamiliar in a place they seldom entered, like a cat placing a tentative paw on a path it does not habitually walk.

I woke up; far away in time I seemed to hear another chiming, and I lay in my chair, confused. For a few moments a deep sense of loss immobilized me. Then I sat up and my glasses, which had been resting on my chest, fell to the tiles. I picked them up slowly, wiped them clean with my shirt, and found the letter which I had been reading lying under the chair. It was an invitation from the Penang Historical Society to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War. I had never attended any of the society’s events but the invitations still came regularly. I folded it and got up to answer the door.

She was a patient woman, or she was very certain that I would be at home. She rang only once. I made my way through the darkened hallways and opened the heavy oak doors. I guessed her to be in her seventies, not much older than I was. She was still beautiful, her clothes simple in the way only the very expensive can be, her hair fine and soft, pulled back into a knot. She had a single small valise, and a long narrow wooden box leaned against her leg.

“Yes?” I asked.

She told me her name, with an expectation that seemed to suggest that I had been waiting for her. Yet it still took me a few seconds to find a mention of her in the vastness of my memory.

I had heard her spoken of only once before, by a wistful voice in a distant time. I tried to think of a reason to turn her away but could find none that was acceptable, for I felt that this woman had, ever since that moment, been set upon a path that would lead her to the door of my home. I took the gloved hand she offered. With its scarce flesh and thin prominent bones it felt like a bird, a sparrow with its wings wrapped around itself.

I nodded, smiled sadly, and led her through the house, pausing to put the lights on as we passed each room. The clouds had brought the night in early and the servants had already gone home. The marble floors were cold, absorbing the chill of the air but not the echo of our footsteps.

We went out to the terrace and into the garden. We passed a collection of marble statues, a few with broken limbs lying on the grass, mold eating away their luminosity like an incurable skin disease. She followed me silently, and we stopped under the casuarina tree that grew on the edge of the small cliff overlooking the sea. The tree, as old as I, gnarled and tired, gave us a small measure of shelter as the wind shook flecks of water from the leaves into our faces.

“He lies across there,” I said, pointing to the island. Though less than a mile from the shore, it appeared like a gray smudge on the sea, almost invisible through the light veil of rain. The obligation to a guest, however unsettling her presence, compelled me to ask, “You’ll stay for dinner?”

She nodded. Then, in a swift movement that belied her age, she knelt on the wet earth and brought her head to rest on the grass. I left her there, bowing to the grave of her friend. For the moment we both knew silence was sufficient. The things to be said would come later.

* * *

It felt strange to cook for two, and I had to remind myself to double the quantities of ingredients. As always—whenever I cook—I left a wake of opened spice bottles, half-cut vegetables, ladles, spoons, and various plates dripping with sauces and oil. Maria, my maid, often complains about the mess I leave. She also nags me to replace the kitchen implements, most of which are of prewar British manufacture and still going strong, if rather noisily and with great cantankerousness, like the old English mining engineers and planters who sit daily in the bar of the Penang Swimming Club, sleeping off their lunches.

I looked out to the garden through the large kitchen windows. She was standing now beneath the tree, her body unmoving as the wind shook the branches and scattered a shower of glittering drops onto her. Her back had retained its straightness and her shoulders were level, without the disconsolate droop of age. Her skin’s suppleness fought against the lines on her face, giving her the look of a determined woman.

She was in the living room when I came through from the kitchen. The room, to which I have never made any changes, was wood-paneled, the plaster ceiling and cornices high and dark. Black marble statues of mythological Roman heroes held torches that only dimly lit up the corners of the room. The chairs were of heavy Burmese teak and covered in cracked leather, their shapes deformed by the generations that had sat on them. My great-grandfather had had them made in Mandalay when he built Istana. A Schumann baby grand piano stood in a corner. I always kept it in perfect tune, although it had not been played for many years.

She was examining a wall of photographs, perhaps hoping to find his face among them. She would be disappointed. I had never had a photograph of Endo-san; among all the photographs we took, there was never one of him, or of us together. His face was painted in my memory.

She pointed to one now. “Aikikai Hombu Dojo?”

My eyes followed her finger. “Yes,” I said.

It was a photograph of me, taken at the World Aikido Headquarters, in the Shinjukku district of Tokyo, with Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido. I was dressed in a white cotton

gi

—a training uniform—and

hakama,

the traditional black trousers worn by the Japanese, staring intently at the camera’s eye, my hair still dark. Next to my five foot eleven inches, O’ Sensei, the Great Teacher, as he was called, looked tiny, childlike, and deceptively vulnerable.

“You still teach?”

I shook my head. “Not anymore,” I replied in Japanese.

She named some of the people she knew, all high-ranking masters. I nodded in recognition at each name and for a while we talked of them. Some had died; some, like me, had retired. Yet others, though in their late eighties, continued to train faithfully as they had for almost all of their lives.