The Glimmer Palace (14 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

“I’m here,” she called out. “I can manage. I’ll take another job. I’ll work days and nights. I went to St. Francis Xavier’s and they told me to come here. I missed one streetcar and had to wait an hour for the next. But here I am.”

Her pace slowed as she reached the entranceway and she saw Lilly’s face.

“Where are they?” she asked.

Words formed in Lilly’s mouth but she could not say them. She swallowed and tried again. Nothing came.

“They kept them together?”

Lilly looked away. Hanne’s eyes crumpled. Her hand flew to her mouth. The hat tipped back and fell from her head. And then with a whimper she sank down to her knees and plucked something from the snow. It was a single red knitted mitten.

The Countess

M

athilde changed her name to Maisie and began to drink afternoon tea. She traded in her dachshund for a beagle and took English lessons every Sunday.Why? Because Maisie had fallen for an Englishman. Stuart Webbs, eagle-eyed detective, screen heartthrob of the day, wears a deer-stalker hat and tweed plus-fours. No thief can outsmart his deductions, no crime scene can fail to offer him that vital clue. And no woman—and here’s the clincher—can as yet resist his charming manners and his doleful smile.

Arrest me, arrest me, breathed Maisie in her dreams. To be handcuffed and led away, to be charged and convicted would be worth any prison sentence. She could warm up his cockles, she would turn his frigid heart red-hot. She would commit a murder to be seized and held in custard, she tells her English teacher, who, purely for his own sadistic pleasure, fails to correct her.

Walking her beagle one day, Maisie wrapped leads with a man with a dachshund. She turned and was about to keep walking when she noticed something familiar about the sausage-dog owner’s face.

“Good afternoon,” she cried out in English. “I am thinking I am in love with you.”

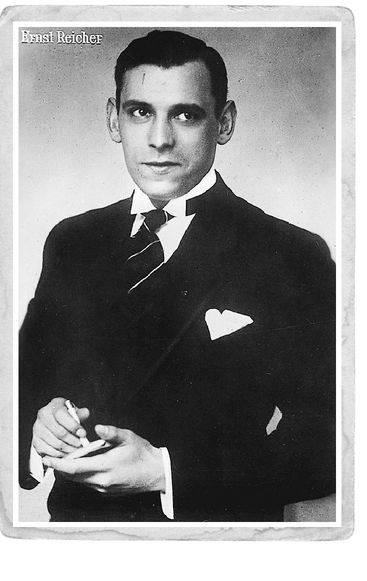

Ernst Reicher stared at the pretty, rich girl with the ridiculous dog. “Pick up your mutt’s poop,” he said in German, “or I’ll report you to the police.” The

very next day Maisie changed her name back to Mathilde, gave away the beagle, and took up horse riding.

Hanne Schmidt, who had arrived an hour too late on the day that the children of St. Francis Xavier’s had been “reallocated,” did not hang around. The light was fading in the winter sky. The rush-hour traffic was beginning to jam. She smeared her eyes with the back of her hand, replaced her hat, and then, without a word, turned and walked back the way she had come, her high heels dragging on the cobbles and her shoulders, in a coat that was too thin for the weather, hunching against the cold.

Lilly could have gone to Leipzig. There was an orphanage with a space for an older girl. And then, if she had wanted, if she had the calling, she could have eventually moved to Munich to the Order of St. Henry. Suddenly memories of Sister August, the swish of her robes on the linoleum, the clank of her keys against her hip, flooded back. Lilly shook her head.

One of the Adoption Society ladies had a sister-in-law who—and here she raised her eyebrow—needed a domestic urgently. Since Lilly was too young to start work in a factory, she had been given directions and an address and told to present herself as soon as she could.

Earlier that day, another of the Adoption Society ladies had put herself in charge of the huge mound of paperwork that remained and, in a fit of domestic zeal, decided to give it away or bin it. Her overefficiency meant that dozens of children were permanently denied the details of their genealogy. This led to untold heartache, such as an episode years later when one mother tried to stop a man she was convinced was her own son, by the likeness to her former husband and the birthmark on his arm, from marrying her daughter. Because of the lack of paperwork, her appeal failed and all her grandchildren died before they were four.

And so, just as she was about to leave, Lilly had been handed a tatty cardboard file. Her full name and date of birth had been scratched out in fountain pen on the top left corner.

“Let’s have a look,” said the Adoption Society lady whose sister-in-law she was being sent to.

“No,” Lilly said before shoving the whole unread file into her suitcase. “It’s private.”

Eyebrows were raised once more and doubts registered. But there was still so much to do, the leftover children to be dealt with and reports to be written, that nothing was said.

After a ride on a tram and a short walk, Lilly arrived at a detached house in the southwest of the city. It was dark and a single lamp burned on the porch. She checked the address and then rang the brass bell. A man wearing evening dress and a top hat opened the door. Loud sobbing could be heard from behind him. He excused himself and stepped back inside, and after a few minutes the sobbing stopped.

“Thank you for waiting,” he said when he returned. “Your arrival couldn’t be better timed. I’m Dr. Storck. Please do come in.”

Number 34 Klausestrasse was a mess. Almost every inch of floor was covered in discarded newspapers. A grand piano stood in the corner, with piles of sheet music held down on the stool by a book; a wind-up record player hiccuped on the window ledge; dead flowers languished in half a dozen vases. As they passed a room off the hallway, the doctor pulled the door shut, but not before Lilly had had time to glimpse who was inside. A woman lay facedown, completely naked, on a table. Her back was covered in glass bulbs. The doctor smiled but did not comment as he led Lilly down a set of stone steps, through the kitchen, and past the scullery.

“This is where the last girl slept,” he said.

He opened the door of a room just big enough for a bed, a small wardrobe, a chest of drawers, and a sink, and switched on the light. A single barred window looked out onto a wall.

“The last girl?” she asked. “What happened to the last girl?”

“Oh, don’t you worry your pretty head about her,” the doctor said. “Did you bring a uniform?”

“Was I supposed to?” she asked.

He frowned and then started to open the drawers of the dresser. Eventually, from the bottom drawer, he pulled out a creased black dress and a stained white apron.

“These should fit. . . . What did you say your name was?” he asked.

“Lilly,” she said.

“Anyway, Lilly,” the doctor went on, “the kitchen’s at the end of the hall and the servants’ washroom is off the pantry. Is there anything else you need?”

However, he didn’t wait for a reply.

“I’m sure you’ll do just fine.”

And then he left, pulling the door shut with a small but final click. Lilly put down her suitcase. So much had happened that day: leaving the orphanage for a final time, arriving at The Adoption Society’s villa, the “reallocations.” She lay down on the bed fully dressed and felt herself fold up inside.

Time passed. A door slammed.The telephone rang. And then, as if emerging from deep water, Lilly sat up and began to take in the room. A couple of metal coat hangers clanged together in the empty wardrobe, a pair of starched sheets bristled beneath a coarse wool blanket on the bed, three black pipes on the skirting whooshed and gurgled, and the tap on the sink dripped. At least she hadn’t been sent to the factory with a printed list of boardinghouses and women’s hostels in her hand. At least, she told herself, she had a place to sleep and a job, even if it was as a servant.

Finally she opened her suitcase. Apart from the box that contained the photographer’s lens and the postcard of the Virgin Mary with Sister August’s ghostly face glued on, there was the cardboard file. Inside was a birth certificate and a newspaper cutting. Under the title “Young Mother Slain in Love Triangle,” the article reported how a former debutante had fallen, first by joining a cabaret group and being disowned by her family, second by conceiving a child out of wedlock, and finally by finding solace in the arms of a student five years her junior. And then, blow by blow, it described the fatal shot that killed her outright, the debate between her two lovers, and the second bullet that the student had fired straight into the Bavarian’s temple.

The cutting was yellow and curling.The victim’s and the perpetrator’s photographs, which before reproduction had been of a reasonable quality, were so faded that it was almost impossible to make out the features. Lilly read the piece three times. If it were indeed evidence of her parentage, her mother’s name had been Emilie Moes, her father was Baron von Richthofen. She tried out the names in her mouth several times over, as if they should have some ring in their tone that she would recognize. But there was nothing familiar about the names or the faces. And when she wept herself to sleep, it was for the other parents, the parents she had imagined and who now, it seemed, were much deader than her real parents, for they had never really existed at all.

“She’s Jewish,” Lilly’s new employer said as soon as she saw her.

“She’s from the orphanage,” said the doctor. “She’s not Jewish.”

“She could be.”

“She isn’t,” he replied.

“She looks it,” said the woman. “Dark, big eyes, something about the color of the skin.Well?”

“I’m an orphan,” Lilly said. “But I was brought up Catholic.”

The woman threw back her head and gave out a shout of laughter.

“Where does my sister-in-law find them?” she said. “And how old?”

“I’m almost twelve,” Lilly replied.

“Practically a child. Does she think I can’t afford someone a little older? Jesus Christ!”

The woman was wearing a loosely fitting day dress made of blue silk. Although she wasn’t much taller than Lilly, she took up the space of two or three people; she paced back and forth, she fidgeted, she shouted and cursed. Although her hair had been tied up in a loose bun, she had pulled at it until it fell in strands around her neck. But she did not let Lilly see her face; she kept her back to the only light in the room and kept her head turned away or covered up with her hands. Lilly glimpsed an eye, a pinch of skin, a corner of lip, but that was all.

“I pay ten marks a week,” she said over her shoulder. “And tell her she can have every second Saturday off.”

“Won’t she need to go to Mass?” asked the doctor. “Seeing as she’s Catholic?”

“She can go at Christmas . . . and tell her to stop gawking. . . . She’s a gawker, isn’t she, Doctor?”

“Now, Alice . . .” said the doctor. “Her name’s Lilly.”

“But she must always address me as Countess,” the woman said. “And she can go now.”

Lilly turned to go.

“And one more thing,” she said. “I’ll have no tittle-tattle, understand? Understand?”

“ ‘Judge not lest thou be judged thyself,’ ” Lilly replied.

The woman flinched.

“You know,” she said, “I think I get sent these people deliberately. Aren’t there any normal servants anymore?”

And then she laughed, a taut, atonal laugh that suggested hilarity but also desperation, depression, and insanity.

illy took off the uniform and carefully folded it. Her hand shook as she placed it back in the bottom drawer again and pushed it shut. Working for that woman, Lilly had decided, would be far worse than going to an orphanage in Leipzig or working in a factory. One day off a fortnight, she considered, just one day. How could she live for that one day? She couldn’t stay. She wouldn’t stay. She would walk out; she would take a bus to the train station and go to Paris. And then maybe America. And when she got there, she would invent a colorful past, just as Otto had suggested. She was the daughter of a cabaret performer. Surely she must have inherited something of her.

She pulled on her gray dress again and adjusted it the best she could. As she stood in the maid’s room, however, she looked down at the dress and suddenly noticed that the waist was too high and the hem was frayed.

The window rattled. Outside, it had begun to pour with icy rain. She hadn’t brought an orphanage raincoat. She’d have to buy one. And then she remembered she had spent all the rose money.

Lilly had never had a successful response from God when she had asked for a sign or begged for a prayer to be answered. The dead mouse did not come back to life, Sister August had not returned, and her parents, whoever they were, had left nothing for her but a faded news clipping. Nevertheless, as the rain slashed the window and the wind shook the glass, she prayed, she prayed as hard as she could, with her eyes squeezed shut and her knees pressed together.

When she opened her eyes, it seemed at first as if nothing had changed. The rain was still falling. The wind still rattled through the cracks in the glazing.The cardboard suitcase still lay open on the bed. Inside were her old boots wrapped up in a copy of the

Berliner Morgenpost

. As she unwrapped them, however, an illustration caught her eye: a typewriter.

Learn to type,

read the caption.

Become a secretary, work in an office. Become a student at Pitman’s Academy

. The price of the tuition was available on application, the class size was strictly limited, and the course had a rolling admission. And there it was. A sign.

Lilly pulled her uniform back on again. She would work for the Countess, but only until she had saved up enough money. And then she would become a student at Pitman’s Academy. She would become a secretary like the women in the director of St. Francis Xavier’s office. It was an easy decision. It was the only respectable occupation, other than nun, that she had ever seen a woman actually do. A bell just outside her door rang several times. Clearly she was wanted. She ran upstairs. The doctor was waiting for her in the hallway.