The Glimmer Palace (10 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

From the moment she saw Lilly and Hanne, Sister Maria decided that they were bound to be trouble.

“Do you know the books of the Bible?” she asked them. “In order?”

They shook their bowed heads.

“Psalm Eighty-four? You must know that: ‘I had rather be a door-keeper in the house of my God than to dwell in the tents of ungodliness. ’ ”

They stared at the floor.

“Just as I thought,” she sighed. “I think we should split you two up.”

They were moved to opposite sides of the dormitory and were not allowed to sit together at mealtimes. As for the rose garden, it was placed out of bounds. Sister August saw it all but did not intervene. It was as if she had lifted her hands. Sometimes, to Lilly at least, the night they had followed her seemed like a feverish dream.

“Maybe it wasn’t Sister August,” Lilly whispered in the bathroom as they were getting ready for bed.

“Course it was,” said Hanne, her mouth full of toothpaste.

She gargled and then spat into the sink.

“You are coming out tonight?You haven’t changed your mind?”

“Course not,” Lilly said.

At just after nine, the girls met at the window of the bathroom on the first floor. For the first time ever it was locked.

“Let’s try the downstairs,” whispered Hanne.

They tiptoed along the corridor and down the stairs. It was too risky to try the main doors.They would be locked with several heavy bolts apiece.

“A window?” whispered Hanne.

The windows in the dining room were long and opaque. There was a single pane right at the very top that could be opened with a long pole. It was, however, nowhere to be found. Lilly balanced one chair on another, climbed up, and unfastened the lock. And then they heard the sound of heavy footsteps on the stairs.

“Just where do you think you’re going?” Sister Maria shouted.

“Go!” shouted Hanne, and gave Lilly a shove from below. “Wait for me at the wall.”

Lilly threw herself up and over the lip of the sill, balanced for a second, and then tipped and fell headfirst into a lilac bush. Through the window she could see Hanne, her hands flat against the glass, her face blurred as she climbed the chairs. Eight white fingers appeared and clutched the sill. One buckled boot was thrust through the open window. She was almost there, but not quite. As Lilly watched, Sister Maria’s figure appeared below. Her hand grabbed an ankle and pulled. Hanne’s boot slipped back, the fingers lost their grip, and Hanne and all the chairs went tumbling down into the dining room.

Lilly lay on the top of the wall and waited. Hanne might still escape; it wasn’t impossible. The street below, now filled with fallen leaves, seemed hostile and dangerous. The trains on the S-Bahn wailed as they passed, and the shadowy figures beneath the archways seemed more numerous than usual.The air was charged.There was a storm coming. The sky pressed down on the city like a palm on clay. She couldn’t go out alone. But she couldn’t go back, either.

Hours later she was awakened by the rain.The street was dark and wet. Hanne wasn’t coming.

Sister Maria was waiting at the main door when Lilly appeared, soaked through and shivering.The nun marched her to the pantry and told her that, in all likelihood, she was destined for hell. Before she locked the pantry door and turned out the light, Sister Maria suggested that the only thing that could save her were several hundred Hail Marys, but even then her salvation was doubtful.

By the tenth Hail Mary, Lilly’s teeth were chattering so much that she could hardly speak. By the time she reached the thirtieth, her fingers and toes were numb. On her fiftieth Hail Mary, Lilly’s head had begun to spin. Where was Sister August? And how could she have let this happen to her?

When Sister August discovered her the next morning, Lilly was delirious. She was taken straight to the infirmary, where she fell in and out of consciousness for three days. In her nightmares Sister August had a thick red beard and was kissing Hanne. Lilly knew that if she didn’t finish the Hail Marys she might spend eternity in purgatory, but every time she started, the words tumbled out in the wrong order and her fate was confirmed.

One night she woke up to the taste of lemons and thought she was three again. She saw Sister August leaning over her with a glass in her hand and loved her unconditionally. But then Lilly remembered in glimpses what had happened and the world started to turn too fast and make no sense.

There was no one around when she finally opened her eyes one morning and knew where she was and why. The fever had lifted, and although she felt a little shaky, she made herself get out of bed and go look for the nurse. The corridors of the orphanage were deathly quiet; the classrooms were empty, the garden deserted, and the door to Sister August’s room had been left open. The children, Lilly later discovered, had all been ordered to attend a daylong retreat.

She found the nurse in the kitchen making porridge. The nurse hurried Lilly back to bed and tucked her in. As she ate her porridge, the nurse answered her questions. Hanne had been expelled. Nobody knew what Sister August said to the other nun, but she had left suddenly and without explanation. Sister August’s departure had been more recent. She had set off the day before, leaving her habit and veil on her bed. No one, not even the convent in Munich, had any idea where she had gone.

The girl’s eyes did not leave the nurse’s face as she recounted the news point by point, and for a moment she almost believed she had overestimated her patient’s possible response. But then Lilly dropped the spoon into her half-eaten porridge and let out a low, thin cry.

“She’ll come back?” she begged the nurse. “Won’t she?”

Lilly’s response was generated by sheer, blinding panic. The thought that she might never see Sister August again made it hard to breathe. And so she cried without inhibition, like a small child who realizes she has been abandoned. Although she had been angry with her, Lilly had never suspected that this would happen. Hadn’t she loved Sister August enough? What had she done?

“Won’t she?” she repeated.

The nurse pretended not to hear the question.

“She waited until she knew you were getting better,” the nurse said softly as she stroked the girl’s distraught little face. “You were one of her favorites, you know.”

But this did not seem to offer her any comfort at all.The child was inconsolable.

The nurse cleared the porridge away and started to wash up.With so much to do, she couldn’t waste any more time.There was another piece of news, which, wary of upsetting the child further, she had failed to mention. After Sister Maria’s visit, the order in Munich had decided to cancel all involvement with the orphanage. On hearing this, the industrialist’s descendants had decided to sell the building. St. Francis Xavier’s closing had been determined, effective immediately.

The Blue Cat

B

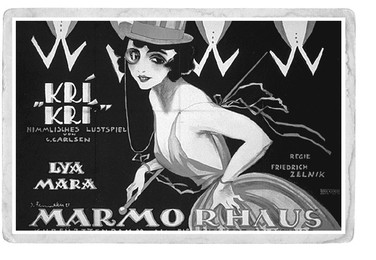

erlin: the opening of the Marmorhaus Cinema. Constructed of solid marble of the palest hue with only the whisker of a crease here and there, the walls seemed to glow in the twilight, as if lit up inside by candles. At the main door, a man with a reel of tickets was placed to collect overcoats and evening cloaks. And then, one by one, the hansom cabs drew up and carefully deposited their passengers into the rapid blinking of the photographers’ flashes.

Inside, a Negress in a white dress mashed out tunes on a piano. A dozen waiters stood with trays of perfectly balanced glasses of Champagne. Although the light was soft and inviting, the décor was everything but: a screaming-red bar, silver sculptures of maidens and horses, painted monkeys swinging from the ceiling—as if, someone said, in the lines and colors, twisting and clashing, banging and clanging, racing and crashing, beauty herself was undergoing a radical reinvention. It’s modernism, someone pronounced; Cubism, another argued, Futurism, Secessionism. No, it’s Marguerite Carréfrom Bourgeois-Paris. The theater, for one night only, had been doused in French perfume.

The privileged invited took their seats in the auditorium; and then, as the lights lowered and a hush descended, they realized as one that the Marmorhaus, for all its glory, was only the portal.The curtains parted and a film started to roll.

Lilly saw Kaiser Wilhelm II for the first time on a Thursday in February 1912. A thick fog had been lying across the city all morning, and by mid-afternoon there was the taste of snow in the air. She heard the military procession long before she could see it. Marches played on brass instruments lifted above the rooftops, and drums, the distance throwing them out of beat, boomed along the gutters, sending handfuls of indignant pigeons into the sky. Lilly reached the Unter den Linden just as the kaiser’s open-topped automobile was approaching. As the car passed, she glimpsed his face, his huge dark mustache, his withered arm, and the sweep of his pale hair.

Of course, Lilly had seen him before on the cinema screen, walking with the empress and Crown Princess Cecilie in the palace gardens, opening regattas and launching warships. Wilhelm II was so fond of “film art,” as he called it, that he would turn toward the lens, give that famous smile, wave that informal wave, or tousle a child’s already tousled hair at the smallest prompt. That afternoon there were no cameras to focus on his smile, but he smiled nevertheless: at his subjects, at the huge crowds, at his city. Beside him, on the soft gray leather seats, sat a dignitary with white whiskers and a slightly morose expression.

“Hooray for the kaiser,” a young man shouted from a lamppost. “And hooray for Franz Josef, the Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary.”The applause was spontaneous, the noise almost earsplitting, the emotion palpable, as both men reached up, touched their hats, and set their decorative feathers aquiver.

A few seconds later, there was a small explosion, followed by the skittering somewhere close behind of horses’ hooves. The royal car slowed down and stopped. The kaiser and the emperor both turned and peered back. But it was nothing. A child with a firework, that’s all, the whisper went through the crowd.

Franz Josef had come to Berlin to talk to the kaiser. He was worried about the Balkan states’ plans to form a league with a view to taking on the Turks over Macedonia. And so, when Lilly stared into the face of Wilhelm II, as if she could make him return her gaze by willpower alone, his mind was most likely on politics. His eyes glided across the blur of a thousand citizens and the flutter of a hundred flags and he did not see the face of Lilly Nelly Aphrodite, now just eleven, even though in his later years he would have given anything—well, almost anything—to catch that gunmetal gaze just once.

The brass band began another tune and the royal parade, first the kaiser in his brand-new Daimler, then the mounted infantry, and finally the goose-stepping cavalry, moved on and headed toward the Brandenburger Tor. As the car approached the stone arch, the procession slowed—this time on purpose—and stopped. On the top of the arch the Goddess of Victory rode in her chariot. Down below, the once king of Prussia, now ruler of Imperial Germany, stood up in his seat. A pair of guns fired. A clutch of swans honked. A horse farted. For a fraction of a second Berlin held its breath. And then Wilhelm cleared his throat twice and saluted. The crowds cheered until they could cheer no more. Dozens of hats were thrown up into the white sky and many were lost forever.

It would be six years before Lilly saw the kaiser again, in a train station at midnight. He missed his chance to meet her gaze at that moment too. His eyes, you see, would be too full of tears.

The parade ceremoniously processed into the park until, soldier by soldier and horse by horse, it gradually dissolved into the fog. On the Unter den Linden, the people watched until their eyes strained, until there was nothing more to be seen. And only then, when the procession was finally over, were the barricades pushed aside, the flags rolled up for next time, and handkerchiefs that had been waved used to wipe the faces of overtired children. Couples hurried home, their backs hunched in their coats, the smoke of their cigarettes floating behind them in dirty halos. Along Wilhelmstrasse and Dorotheenstrasse, the streetlights buzzed on, bright pink globes in the dusk. And with just a slight darkening of the sky, it started to snow, first a light flurry and then heavy flakes as big as five-pfennig coins.

In the months following Hanne’s and the tall nun’s departures, a lull had descended on the orphanage. The building had been put up for sale and every day a new batch of prospective buyers wandered around, taking measurements or trying to visualize the dismally appointed dormitories as luxury hotel rooms, perhaps, or swanky new apartments.

The orphans, suddenly released from all religious routine, never quite fell into a state of godless anarchy as was expected. Instead, out of respect for their beloved Sister August, the older children kept order, tucked up the younger ones at night, and stuck faithfully to the schedules and rules that she had devised. It was true that several packed up their nightgowns and made their beds for the very last time, but the majority decided to stay until the bitter end. The gates were open wide but there was nowhere, they realized, for them to go.