The Glimmer Palace (8 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

“You’ll marry him tomorrow,” he replied after an overly self-indulgent pause. “And that’s my last word on it.”

The curtains dropped with a flump.

From the left side, a small band of orphans dressed in huge waist-coats and doublets, so long that they reached their ankles, skipped slowly across the stage, hitting cymbals and tambourines. A train on the S-Bahn passed outside the window so close that the whole hall shook along with the instruments.

When the curtain was pulled up again, the suitor had his arms folded and was tapping his foot. Since he could never remember any lines, the suitor hadn’t been given any. The king sat on a throne that Sister August recognized instantly as one from the chapel.

“My dear daughter, Wilgefortis, will be here any moment to marry you,” he said. “Ah, here she is now.”

Tiny Lil was now wearing a long veil over her face. The suitor rubbed his hands. He was a foot smaller than his bride. They stood side by side. Tiny Lil whipped off her veil. The suitor jumped back in horror. Someone stifled a snigger. She wore a huge red fake beard, borrowed from a production of

Falstaff

.

“What have you done?” said Tiny Lil’s possible father when the laughing from the younger orphans in the front row had almost stopped. “He’ll never marry you now.”

“It was God’s work,” she replied. “He answered my prayer.”

“You’ll pay for this,” yelled the actor. “With your life.”

The audience, as one, turned and raised their eyebrows at each other. Sister August closed her eyes and breathed out very slowly. Her fists were tightly clenched in her lap.

When the curtain was yanked up again by a child on the balcony above, Tiny Lil, still wearing the beard, was tied to a cross. She took two deep breaths and then expired. The king and the suitor clinked a couple of tankards and pretended to drink. Nothing happened for a couple of seconds, and Tiny Lil’s eyes flickered open as she tried to catch someone’s eye left of the stage. Finally a small boy walked onstage dressed in torn and dirty clothes, playing a Gypsy tune on a fiddle. He paused at the would-be dead girl’s feet. She kicked off one of her boots. He picked it up.Wernher, who was proud of the fact that he never missed his cues, strolled onstage just at the right moment.

“How dare you steal my dead daughter’s gold boot,” he hissed.

“But she kicked it off,” the boy replied.

“How could she? I had her crucified. I’ll crucify you, too, I think.”

“Let me prove my innocence,” he pleaded. “Let me play again and show you.”

The boy played.The actor glanced briefly at the audience.They all seemed transfixed—all except the nun, and that could only be expected. Tiny Lil let him play on, longer than she had done in rehearsal; and then, with all her might, she kicked off the other golden boot. It flew up and turned round and round in the air, toe, heel, toe, heel, and then sailed down in a curve, struck the general on the head, bounced up again, and fell straight into Sister August’s lap. Finally the nun looked up.

“So you are innocent after all,” the actor proclaimed. “And my daughter was right.There is a God.”

Here he threw himself on the ground and started to sob noisily.

“She was a saint, Saint Wilgefortis. And you can keep the boot.”

And with that, the curtain fell once more and the audience broke into a somewhat unconvinced round of applause. Still wearing her beard, Tiny Lil came out from behind the curtain and took a bow. A few of the actors whistled. One of the actresses had been laughing so hard all the way through that she had to run to the bathroom. The general stood up and proclaimed that he had to leave immediately for another engagement. The contribution plate was awash with ten-mark notes, but the damage had been done. Sister August had proved that she was everything the general had assumed. As she said good-bye and thanked the audience for coming, the nun’s face was ashen. She still held the boot. Some of the gold paint had come off on her hand.

“Lilly,” she said when the last of them had left, “I want to see you in my office immediately.”

It was at this point that God’s singularly effervescent light switched itself off in Tiny Lil’s mind for good. A puff of dirty cloud blew across the sun and she suddenly felt a small black hole open inside. She didn’t care about what anyone thought apart from one; she had written the play for Sister August, to make up for the textbooks. God, all-seeing, knew, so why didn’t she?

“My office,” the nun repeated.

By the time that Sister August summoned Lilly, as she was known from that day, from the bench in the corridor where she had been waiting, her fury had subsided. She had lost three hundred marks, but the children wouldn’t starve. Her own battle, however, was looking increasingly like one she was going to lose. Still wearing her white dress and crown, Lilly stood for several moments before the nun noticed her. And when she spoke, it was not in her usual voice.

“You know,” she said softly, “when I joined the order, I thought I could do some good, save some poor innocent children from the clutches of poverty and evil. But now I’m not so sure.”

Lilly struggled for something to say.

“Apart from taking the bishop’s chair from the chapel,” she said eventually, “you made a mockery of the saints.”

“She was real. I read about her in a book.”

But Sister August’s mind was already elsewhere and she didn’t appear to hear Lilly’s reply.

“You can go now,” she said.

Lilly ran out of the orphanage and stumbled straight through the general’s rose garden, scattering loose petals and string and bamboo stakes. She tripped on a root and grabbed hold of a briar. A drop of blood beaded on her finger. It ran down her hand, mixing with gold paint until it left a trail of sticky, gory glitter. How could she have been so wrong? She threw herself down on the damp black earth and let self-pity overwhelm her.

It was late summer. Autumn was in the air and she shivered as she lay prostrate in the rose patch. The sky was steel gray and punctured with stars.A motorcar passed on the street outside and blew its horn.A formation of wild geese flew just above the rooftops toward the river.

And then she noticed that many of the precious roses, the Schneekönigins and Gallicas, the Albas and the rare Damask Perpetuals, some grown from cuttings by the general himself, were headless.

“You’ve been stealing roses,” she whispered to Hanne that night.

“Sister August will find out.”

Hanne rolled over until she was facing Lilly. Her lids were heavy and her lips were dark red in the moonlight.

“Why should I care?” Hanne replied.

“Because stealing is a sin,” Lilly said automatically.

Hanne barely blinked.

“The more you pick, the more grow back,” she said. “So how can it be a sin?”

For a moment the two girls looked at each other: Hanne, limp and always tired, her arms draped around her small blond head; Lilly, wound up, curled round and round like a spring, her eyes so large that she seemed closer, much closer than she really was.

“Don’t you want to know what I do with them?” asked Hanne.

“What?”

“I go to bars and tingle-tangles and sell them,” she said. “Men buy them for their sweethearts. I’m saving up.When I’ve got enough, I’m leaving this place and I’m taking the boys with me.”

Tingle-tangle: Lilly repeated it over and over in her head. Even though she knew a tingle-tangle was just another name for a seedy bar with performing girls, the word itself somehow suggested someplace magical.

“Hanne?” Lilly whispered.

She stirred.

“What is it?”

“Can I come with you?” Lilly asked. “Can I help you sell roses?”

“Course,” said Hanne. “Why else do you think I would have told you?”

Tingle-tangle

E

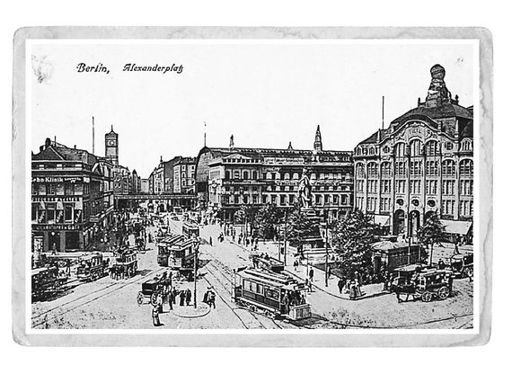

very evening for a year, barring church holidays, and days off due to ill health, Arnold von Heidle and his wife, Hilda, attended the Union Movie Theater in Alexanderplatz, Berlin. Two hundred fifty films they witnessed, incognito, to assemble their extraordinary statistics. And this is what they saw: ninety-seven murders, fifty-one adulteries, nineteen seductions, thirty-five drunks, and twenty-five practicing prostitutes.

The von Heidles, upstanding members of the Catholic Church, darlings of the diocese, give well-attended talks to church groups on the newest danger to the nation: the cinema. Proposing a blanket ban on filth in word and picture, Arnold, his dear Hilda nodding, reveals that the urban masses are squandering their hard-earned cash on the creations of squalid minds.What we need, he tells them all, is censorship.

Censorship: to snip and cut, to shred and paste miles and miles of celluloid. Arnold’s mind drifts: as smooth as black silk stockings, as slippery as a concubine’s cunt pumping out of the machine in one unspooling lick. He feels a nudge. Wake up, dear, are you ailing? He clears his throat and then continues. Films, he utters to the silent assembled, are the devil’s handiwork. For a second it is so still you can hear the stroke of strung pearl on pure cashmere. And then Hilda, her timing perfect, begins to sob.

Lilly placed one foot on the ledge that had once held her shrine to Jesus and the Virgin Mary and pulled herself up with her fingertips onto the top of the wall. Over the other side, a tram rattled past, its windows filled with golden light in the cool blue evening.

The bricks were mossy and damp underneath her skirt. She sat astride the wall and waited for Hanne to pass her up the basket.

“Hurry up,” she whispered. “Someone might come.”

She could see shadowy figures underneath the arches of the S-BAHN across the street. The clip of a gentleman’s shoes approached from the park. A man walked below her, so close that she could have almost reached down and touched the top of his hat. When he had turned the corner, Hanne passed up the basket. Lilly took it and then let herself drop down softly onto the pavement.

Hanne appeared a few seconds later and jumped down. It was nine in the evening.The main door was locked, but they had climbed out of the bathroom on the first floor. Nobody, Hanne assured her, would miss them until the morning.

“You still want to?” Hanne asked her.

Lilly nodded. The air was charged. She trembled although she wasn’t cold.

“Don’t worry: she never goes out at night,” Hanne said.

Since the night of the play, Lilly had avoided Sister August. If she ever heard the swish of her skirts approaching or the clank of her key chain, she would turn and walk in the other direction or duck into a dark corner. One day when she was heading to a class, however, the nun suddenly burst out of her room.

“Lilly,” she had said. “Lilly?”

Lilly’s steps slowed down and she stopped. Then she waited, her gaze fixed to the floor in front of her. Sister August had chastised herself over and over for not insisting that she see the play first.What had she been thinking of, to let a cabaret performer loose on her children? And now Lilly would not look at her. And she was suddenly overwhelmed with nostalgia for the little hand that had stroked her habit as she prayed for the kaiser on his birthday.

She had also noticed that Lilly had found a friend. And although she was aware of a lessening of pressure, like a belt loosened by a notch or the removal of an uncomfortable pair of shoes, she was also uneasy. Lilly knew too little of life outside the orphanage, Hanne Schmidt too much.

“I just wanted you to know . . .” she said.

To know what? Lilly had wondered, her face growing hot and her breathing faster.That God was still watching her? That He was everywhere? Or that she still despised her? The phone began to ring inside Sister August’s room. She would have to answer it. But instead she took a few steps toward her and then awkwardly, clumsily, a little too roughly, embraced her. Lilly’s body stiffened. She waited for more words to come, but Sister August didn’t have any.

She answered the phone before it rang off. Lilly went to the bathroom, locked herself in a stall, and pulled out the postcard of the Virgin with Sister August’s face stuck on, which she still carried in her pocket. She thought about ripping it into hundreds of little pieces and flushing them away. She thought about it but she could not do it. Instead she smoothed down the faded photograph on the dog-eared postcard and put it back in her pocket.

Since that day, however, she hadn’t needed to avoid Sister August anymore: the tall nun rarely came out of her room except for meals and Mass. Sister August had been ordered to go back to Munich to discuss the play, the orphanage finances, and her next position. The actor, Wernher Siegfried, had pocketed the remainder of the three hundred marks and had never come back to pick up his costume. And so, in light of this, there had been suggestions of a return to administration, a noncontact post with less responsibility. Every day, however, Sister August paced up and down before her window, practicing lines of defense and calculating budgets. She did not want to leave the orphanage and go back to licking envelopes. She had made it what it was.This was her true calling; the children needed her, and she them. If only they would give her one more chance.