The Glimmer Palace (4 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

“You’re never alone. God is all around,” she would tell them. “He watches you every moment of the day.”

Tiny Lil imagined that, at Sister August’s instruction, God had punctured a hole in the sky and was training his eye on that patch of land between the river and the bright green park. And when she bowed her head and, side by side, all the orphans whispered the words to the Lord’s Prayer, Tiny Lil’s heart was filled with such hope and light that there was no doubt, no doubt at all, that the nun was right.

Sometimes Tiny Lil looked for God. She explored every inch of the orphanage, from the spaces between the eaves in the attic to a secret cupboard behind the coal bunker in the basement, for evidence of his presence that she could offer to Sister August. And yet she never found anything, nothing but dead spiders and single socks, balls of dust and small locked suitcases that former inhabitants had forgotten.

In the garden, between a yew hedge and the perimeter wall, where the air was a thick dark green and the sky above a strip of bone-white cloud, she laid out two fatty wax candles half burned down, a rusty hat pin, and a faded postcard of the Virgin Mary on a mossy stone ledge. Nobody ever went there. Nobody knew what was there but Tiny Lil. And God, of course. On the day that Tiny Lil gave up on the dead mouse, the day of the orphanage photograph—one of the coldest, incidentally, of 1906—she crossed herself and placed the photographer’s lens next to one of the candles. And then she knelt down in the mulch and prayed for the mouse’s soul.

“Hail Mary,” she whispered. “Hail Mary, mother of Christ.”

She stopped abruptly. Someone was coming through the undergrowth, someone who kicked his way through the leaves and roots, the roosting birds and small mammals, with sheer brute force. She dropped the lens, the candles, and the hat pin into her pocket just as Otto Klint, an eleven-year-old who had been left on the doorstep when he was just a few days old, stumbled out of the gloom. He started when he saw her but grabbed a handful of leaves to hide it.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, and threw the leaves at her.

“Nothing,” she replied.

He examined her for a moment, her small face with its sharp little chin defiant in the half-light. But her eyes would not meet his.

“What’s in your pockets, Tiny Lil?” he said, taking a few steps toward her. “I’ll tell Sister August.”

“Nothing,” she said again, her voice rising in pitch.

Otto held her wrists together with one hand and emptied her pockets with the other. He looked through her things briefly, then handed them back to her again.

“Sorry,” he said briefly. “I thought you might have a cigarette.”

Then Otto sized up the wall. It was two meters high.

“I won’t tell if you won’t,” he said.

Tiny Lil finally looked up at him. His fair hair had been shaved after a recent outbreak of lice and his thin face looked hungry. He smiled and it seemed too generous an expression for the pared-down proportions of his face.

“Right, then. See you later,” he said. “Little Sister.”

Otto turned, placed one boot on the ledge, and levered himself up. With a grunt of effort, he grabbed the top of the wall with both hands and crawled over. She listened as his boots hit the paving stones with a dull, hollow thud. On the other side of the wall the streetlights came on with a flicker and a buzz. The ground shuddered as an omnibus thundered past. A bell was ringing. The birds were settling back into their nests. Tiny Lil picked up the postcard of the Virgin Mary.The black imprint of Otto’s boot covered her face. She tried to brush it off but the mud streaked and stained it. She licked her finger and rubbed and rubbed until there was only a gray smudge where the face had been.

Luckily the photographer gave the orphanage a dozen prints of his photograph, of varying quality. When one went missing and Sister August found it in the dustbin with a single hole in the middle of the image, nobody claimed responsibility. The proof of Tiny Lil’s crime, if it had ever been found, was a grubby postcard of the Virgin Mary with Sister August’s semitransparent face stuck on.

Seven Hundred Kilometers

Y

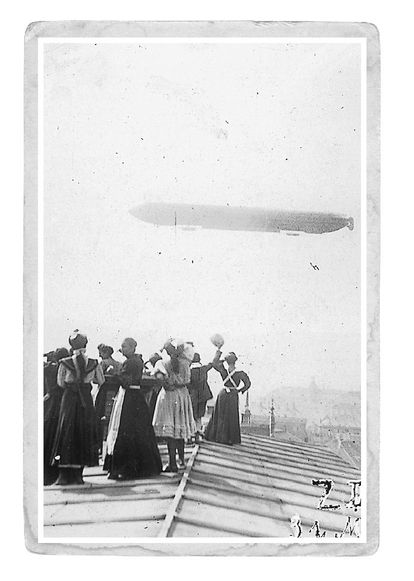

our hat’s in my shot, madam. If you would be so kind as to shift a little to the right.” On the zeppelin LZ6’s maiden flight are forty passengers, six crates of

Sekt

, one moving-picture camera, and twenty reels of film. Hans von Friedrich ducks under the hood and starts to crank. Below, the world slowly unrolls: lakes like discs of glass briefly scored by the flight of a swan; a train crossing an elevated steel bridge, three ponies cantering, a girl on a bicycle who stops and waves hello, hello, hello.

Hours later but right on schedule, here’s Berlin. Charlottenburg; the Schloss, perfect as a jewel; the zoological gardens, where elephants, zebras, giraffes all look up at this long black blot against the sun. The Tiergarten, green and soft as velvet; ladies in their boats; a brass band playing in the Englischer Garten. Then the Unter den Linden, St. Hedwig’s Cathedral, the opera house, and the university. Look there, and there. Hundreds, maybe thousands, have come out on their rooftops to watch the zeppelin’s slow descent. The airfield comes close, and closer still. Men on the ground pull on the ropes. And here to greet the LZ6 is the empress herself. Three cheers for the rigid dirigible. “Is my hat in your shot?” the lady asks. “No, madam,” says Hans von Friedrich, whose grasp of mathematics is rudimentary. “But I seem to have run out of film.”

Tiny Lil loved Sister August. Although it was sinful, she loved her more than the Virgin Mary, she loved her more than Jesus. At mealtimes she sat not beside her, as that wasn’t allowed, but at the nearest possible table. At Mass she sang the responses in Latin, loud and clear so she would be sure to be heard. She hovered around Sister August’s closed door, waiting to be asked to run an errand or pass on a message. And once, and only once, when she was sitting behind her in a special service for the kaiser’s birthday, she leaned over, inhaled the clean almond smell of her, and ran her finger down the stiff brown slope of her habit.

Sister August noticed, of course she did, but she had so much more to think about than one little girl’s attachment to her. According to the

Berliner Morgenpost

, the population of Berlin had risen to more than two million; it had doubled since German unification in 1871. Orphans were being deposited at St. Francis Xavier’s at the rate of a dozen a week. Some were not even genuine, but the overspill of the large families who were leaving their farms in Silesia or Pomerania and moving into two-roomed apartments in Wedding or Rixdorf. An ever-increasing number of other babies had just been dumped on the doorstep in milk crates or cardboard boxes with no sign as to where they had come from or why.

The director, a distant cousin of the founder—a man who sat at a large, empty mahogany desk all day and never seemed to actually do anything—did not appear to think it was a problem.

“The more, the merrier,” he sometimes said. Or, “Let them eat cake.”

He was large and lugubrious, and suffered from excessively sweaty hands and chronic catarrh. He employed a series of women as secretaries whose only visible duties were to type his correspondence, hang up his coat on a polished brass peg, and make him coffee with exactly the right amount of sugar. Some days he looked deep in thought as he leaned back in his leather chair, with an expression that suggested he was mulling over the nature of philanthropy or the ethicalproblems stirred up by Fontane’s new novel,

Effi Briest.

In fact, he spent much of his time wondering whether to make a pass at the women he had hired and, if he did so, if he could keep an affair on the boil without his wife finding out. It was a fantasy, fortunately for all concerned, that never got further than the brush of a damp hand on a well-padded bottom or a lingering Christmas kiss.

It was to him, in an attempt to involve him somehow, that Sister August brought the orphans who had gone way beyond the limits of so-called acceptable behavior. Uncomfortable with children, as he had only one son, whom he had sent to boarding school, the director would tell the children to lie across a piano stool and then he would beat them on the bottom with a slipper up to ten times, depending on their crime.

“It obviously works,” he told the nun. “Just look at Tiny Lil.”

However, the slipper, a Turkish shoe with fancy embroidery, was flimsy and soft. The director’s aim was poor and his blows were feeble. It was not the physical pain that made the director’s slipper beatings so distressing, but the unpleasantness of being beaten by a man whose hands dripped and who coughed loudly and repulsively after every stroke.

The sister regarded the director with notable and understandable disdain. He was scared of her and attracted to her in roughly equal measure. And when she spoke, it was not unusual for him to fail to hear a single word, so smitten was he by the bloom on her perfect virgin’s cheek.

“So you’ll do it today,” she would say after suggesting once again that he write to the founder’s family to solicit more funds.

“Of course,” he would answer, although he didn’t know what she was talking about, as he hadn’t been listening. “I’ll do it immediately.”

And so it was left to Sister August to deal with the ever-increasing volume of children on a fixed budget while the director drank his coffee, stroked the shiny sole of his embroidered Turkish slipper, and contemplated a series of particularly becoming behinds.

New beds were ordered on credit and a dormitory was set up in the gymnasium. Boots had to be bought for those who came barefoot, and more food had to be prepared in the kitchen than it could realistically produce. God, the factory owner’s widow—who was growing increasingly parsimonious—or, as a last resort, the Sisters of St. Henry would have to provide. If only, Sister August thought to herself when she was well away from the chapel, men and women would stop fornicating. The director was almost sixty. And once he had retired, she would take the seat behind the mahogany desk and quickly fill up the drawers with leaflets on abstinence.

Nuns joined her and nuns moved away, claimed by poor health, rheumatism, or nervous exhaustion. Few had the vitality or tenacity of Sister August. Her blue eyes were chipped with determination; her full mouth was a straight line unbroken by the exercise of smiling; and her hands, although often chapped and blistered, were long-fingered and dexterous. She had just one indulgence, just one: in the long, quiet afternoons, which she had set aside for paying bills and transcribing medical records onto thick green cards, her mind would start to drift and her index finger would slip down between her legs. She did not consider it a sin. She would always stop herself or, more usually, be interrupted by a crying child or a ringing telephone well before she reached the place her body longed to go. And so Sister August was often breathless and a little flushed, as if she had just run up a flight of stairs or been informed of some awful tragedy.

“Hello?” she would sob into the receiver. Without a word, many women would replace the handset, lift up the baby they could not afford to keep, and reconsider.

Tiny Lil had known for as long as she could remember that when they were fourteen, the children had to leave the orphanage. The girls went to work in the owner’s underwear factory and the boys to a chemical plant or military service. Some, like Otto, left willingly with a round of kisses and a promise that he’d come back and visit. Others had to be forcibly removed and were led out after dark when it was thought that no one would hear their distress. But Tiny Lil couldn’t imagine a life outside St. Francis Xavier’s or a single day without Sister August.

By the time they left, most of the orphans could read and write. It was written into the factory owner’s legacy. He had learned to his own cost that a workforce that could read the safety signs was preferable to one that could not.

Because of the rise in population, all the local schools and gymnasiums were full.The orphans were educated instead in a couple of large attic rooms. Sister August taught the younger children literacy and the elder ones elocution. They all learned to write using India ink and chancery cursive and could drop their guttural vowels when required and speak with the softer accent of Sister August’s native Munich.

In 1909 the orphanage had half a dozen teachers on loan from the university. They had only one thing in common: they had fallen for Sister August’s dynamic charm and agreed to teach at St. Francis Xavier’s on an ad hoc, no-fee basis. Some immediately regretted it and secretly considered it unwise to educate the children and give them false expectations. Others were worried that they might catch an incurable disease, and opened the windows whatever the weather. But, despite their grievances, the orphanage did have one thing going for it: it was a place where they could practice lectures or just waffle on about their own particular passions without any scrutiny whatsoever. Sister August knew that the 1909 syllabus, which included the habits of the fruit fly, German poetry, and a minor German painting school that specialized in the portraiture of dogs, did not make a rounded education. But until she could offer an alternative, she wasn’t in any position to rectify it.