The Glimmer Palace (31 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

The Screen Test

T

he Berlin premiere of

Carmen

was packed. Up onstage, Pola Negri, in a glittering silver dress, shook the hand of the director and blew kisses to her fans. The orchestra began to play the Toreador song and the audience took their seats. “But why,” she whispered, “do they open the Champagne now?” The orchestra played louder and a little louder still.“It’s gunfire,” someone explained.

Afterward, at the reception, the Champagne bottles were finally opened— one, two, three, four—until there was a virtual symphony of bangs and whistles as the rifle fire drew closer. Later, nobody wanted to leave: nobody but Pola Negri, still dressed in glittering lamé; nobody but Pola put down her glass and pulled on her coat. “There are no taxis,” she said in an accent heavy with her native Polish. “But the trains are still running, aren’t they?”

They begged her, they implored her, not to risk her life, but Pola Negri had died on screen a dozen times and said she wasn’t scared. And so she left the theater and, with her body pressed to the wall, edged slowly, slowly, along the empty block to reach the U-Bahn. A bullet ricocheted into the wall, a window smashed and showered her silver lamé dress with glass, but still she caught her train. Only later would she admit that she had wept all the way home.

It was snowing outside again and the electricity had been off all day. Even though it was strictly forbidden, according to the set of handwritten rules pinned to the back of the door, Hanne lit two dozen candles and placed them in saucers all around the floor. It was extravagant to use so many candles, but she had bought ten boxes full from a crooked churchwarden.With the snow coming down and the flickering light, the room was filled with dark shadows and reflected radiance.

“And now,” Hanne said, bringing out a brown glass bottle, “let the conversion begin.”

At first the peroxide felt ice-cold on Lilly’s scalp. It trickled down the back of her neck and dribbled behind her ears. Hanne combed it through and then wrapped Lilly’s head in an old towel. The smell made Lilly’s eyes water. She held her breath but the taste was still in her mouth. And then it started to burn.

“It’s supposed to hurt a little,” Hanne explained. She had already bleached her own hair white, like a child’s. Or an angel’s.

The scissors cost twenty marks from a department store. They were clean and shiny and ever so slightly oily. Two hours later, after washing Lilly’s hair in cold water, Hanne began to cut.

“There,” she said eventually.

All around her chair lay little piles of yellow fluff. Lilly’s head felt light. Her neck was cold. Hanne led her to the mirror above the sink with her eyes closed.

“Now look,” she said.

Lilly opened her eyes. Instead of long and dark, her hair was short and blond. A golden curl fell over her cheek. Her fringe was swept over her brow in a brave yellow wave.

“You look a million times better,” Hanne said. “But I haven’t quite finished.”

Hanne took out a stick of black kohl and drew on two arched eyebrows. Then she filled in Lilly’s lips with dark red stain. Finally she pulled out a sour-smelling washcloth and covered her face with a cloud of white face powder.

“Now all you need is a new name,” she said. “How about Lida or Lulu or Lidi?”

The film producer’s “studio” was a glass conservatory in a villa in the west of the city. The previous owner had used the room to grow tomatoes and it still smelled of fresh earth and mold. The “set” was a flat white wall at one end and a faded green velvet sofa.The film producer stood behind a huge camera and introduced them both to the director, a tired-looking man in his fifties. He explained that they each had to do a screen test, to see how they looked on film. They weren’t the only ones. Half a dozen girls sat in the hallway, every one an actress, every one, or so they claimed, “a special friend” of the producer.

Hanne sat on a sofa as she was told. Her face was rigid with tension. She clenched her shoulders and she bit her nails. She crossed her legs and uncrossed them again. And then they were ready. With several twists of his wrist, the director cranked up the motor of the camera. He settled himself behind the lens and made sure the film was threaded through the sprocket correctly. And then he ordered silence and his fabulously expensive Ernemann Kino started to roll.

Underneath a heavy winter coat, Hanne Schmidt was wearing her lucky dress, a white satin dress, which in her experience was always shed more quickly than any of her others. Her feet were in heels, her hair was in curls, her face was painted. But the camera ticked like a heart, like a heart beating way too fast. It was so loud that it seemed like the very sound of anxiety itself. Hanne’s eyes darted from the film producer to the director and back again.

“Running,” said the director. “Now strip.”

Hanne’s mouth fell open for a fraction of a second. And then she visibly relaxed. It was going to be okay. To sit passively was almost impossible for her. But to take charge, to perform, was something she knew she could do. She stood up and slowly took her coat off. And then her lucky dress. And then she started on her underwear.

“Very saucy. . . . Now give me a smile.”

Hanne stopped so suddenly that she laddered her stockings, the stockings that had cost her five marks and she had bought only that morning. Then she wrapped her arms around herself and shook her head.

“What, you can strip but you can’t smile?” the director said. “Is this how girls from Berlin are now?”

The producer knew a dentist who could fix her front tooth, but it would cost a lot. Hanne got a part anyway. She would play a police inspector’s daughter who revealed one too many “secret” files to the hapless hero of the piece.

“Now you,” said the director.

Lilly sat down on the sofa. She was wearing her old winter coat and a new blue silk chiffon dress, cut to the knee with a row of tiny pearl buttons down the back. An investment dress, Hanne had called it.

The bright lights had made the room at the back of the villa hot and damp. The windows were steamed up and the air was stale. But despite the trickles of perspiration that ran down between her shoulder blades, Lilly trembled.The director aimed his mechanical gaze at her and licked his lips. He checked the stock, positioned himself above the eyepiece, and once again started to crank.

“Rolling,” said the director. “Okay . . . let’s go.”

Lilly’s hands reached up and she began to unbutton her coat. Her hair fell into her eyes, yellow hair, shocking to her still, and she suddenly wished it was long again, long enough to cover her face. Her fingers wound around the last of the horn buttons and she pushed it through the buttonhole. Her coat fell from her shoulders. Carefully she pulled down her underpants and stepped out of them. And then, without looking up, she reached behind her back and began to unbutton her dress. The room was completely silent apart from the ticker of the camera motor.

“Beautiful,” said the director.

Lilly stared straight into the camera lens. She could see herself upside down in its beveled surface, her blond hair and her face drawn in with lipstick and kohl. Was she beautiful? For a second or two she didn’t move. As the lights blazed and the camera rolled, as time ticked through the sprockets and frame by frame her image was recorded, she took a breath and was filled with blue sparks, the same blue sparks she had felt all those years ago on the makeshift stage at the orphanage. As then, time seemed to slow down and every single second stretch; she was outside herself, she was free of herself, she belonged to the moment. Although the lights meant that she couldn’t see them, she could feel the gaze of the director, the producer, the camera. And Lilly was suddenly aware of her own ascendancy; she was a temporary deity, momentarily immortal, a fixed point. But following swiftly came a rush of horror: at what had happened after her play, at what she was expected to do now, at how she had just felt. And her eyes began to swim.

“More?” she asked.

“Of course,” replied the director. “Of course more. And make it swift.”

Lilly swallowed and lowered her face. And then she dropped her arms and in a sigh of blue silk chiffon, the dress began to slip.

“I’ve got it,” said the director. “I’ve got it all.”

But he had spoken too soon. Just as the dress crumpled on the floor, just as her pale body, the swell of her breasts, the jut of her hips, and the dark triangle between her legs were unveiled, exposed, revealed, with a flicker and a small surge the illumination, all those hundreds and hundreds of volts and amps and watts, all those brand-new bulbs from Siemens, cut out, leaving the temporary studio in warm black darkness.

At first nobody moved. Only the camera kept turning. They all stood and listened as if the dark were masking something audible. Then the director shook his head at the producer.The producer tried the light switch, on, off, on, off, with increasing force, as if he could rectify the situation with willpower alone.

When it was clear that he could do nothing, Lilly reached down quickly, pulled her dress back on, and reclaimed her underwear. Without the lights, the room in the villa in the west of the city seemed nothing more or less than what it was, a back room in a shabby house in the suburbs. When a dog began to bark in the next garden, the fragile construct that it was a film studio at all was shattered. The girls in the hall swore under their breath, pulled on their hats, and began to leave. They guessed correctly that the power plant workers had gone on strike again. The whole city would be out for hours.

“What about my friend?” Hanne asked the director as he tried to pack up his equipment in the pitch-blackness. “Aren’t you going to give her a part too?”

“Leave your name and a contact number,” said the director. “I’ll take a look at what we’ve got on film and then I’ll be in touch.”

Only three or four frames of the actress who would soon be known as Lidi, however, survived. The director burned out the first half of the roll of film when he accidentally opened the camera later that evening after three glasses of beer. In the film that was salvaged—the few seconds or so during which the director waited to see if the power cut was purely a temporary glitch—the image of Lidi is so underexposed that the almost nude girl in the almost dark could have been anyone. It was just as well, for the rest of his archive would eventually turn up in an auction room and be bought, duplicated, and sold under the counter all over Germany as

Girls on the Casting Couch

.

“I failed the audition,” she said years later of that first screen test. “Thankfully,” she added.When asked to explain, she politely changed the subject.

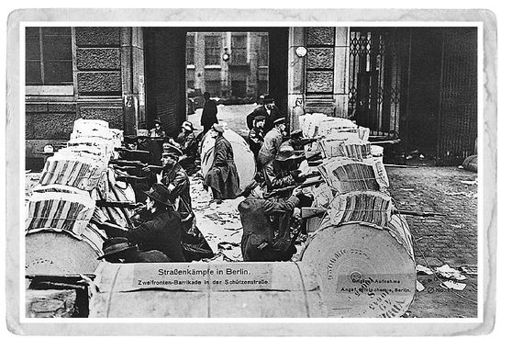

The fighting went on; the center of Berlin had been placed in a state of siege. On her way to buy bread, Lilly found the next street had been sealed off. Barbed wire and barricades had been erected overnight by both the Spartacists and the government troops, and for the next month they moved back and forth, a street or two at a time, a square, a park, a monument lost and gained over and over.

Hanne’s first day of shooting was in another “studio” in East Berlin. The trams were erratic, so she had tried to walk; the streets were covered in masonry and the random stain of congealed blood, but they were still passable. But even Hanne soon decided that it was too dangerous. Bullets ricocheted across the Alexanderplatz and mortar shells bombarded the police headquarters. And the opposing forces didn’t just focus on each other: passing through their checkpoints, pedestrians could be targeted at random for carrying the wrong papers, for offering the wrong answer, for giving the wrong kind of look. And so Hanne called the director from a café on the corner and he reluctantly agreed to send a car.

Hanne’s filming schedule was usually nocturnal. The new tooth was taking longer to pay off than she had anticipated. But she never talked about what happened in the “studio” or where the finished films were actually screened. And Lilly could not help but notice the slow dulling of Hanne’s spirit when it was clear that her new career was not what she had supposed at all but simply a repeat of her last.

And so, at Hanne’s insistence, they both auditioned for revues, for cabarets, for theaters. The counts and princes of Prussia and Bavaria had come back from Mesopotamia, from France, and from Georgia and taken rooms in luxury hotels or reopened their villas. Nobody could ignore the barricades, the bloodshed, and the gunfire, but life went on. People drank, they ate, they drank, they danced, they wanted to be entertained. Together with hundreds of other young women, all dressed in knee-skimming skirts and with short, bobbed hair, Lilly and Hanne waited in dusty back stages or hung around in the stalls until, called one by one to sing, dance, or strip, they would take the stage and do their best.

Lilly, who could not sing or dance or even strip with any real sense of conviction, was never called back for a second audition. Hanne was recalled once to the Chantant Singing Hall in Oranienburger Strasse but was not chosen for the final lineup.

Although Hanne knew she was spending far more than she was making, she had become more extravagant than ever. She bought a wind-up phonograph and a stack of recordings. She had her dresses altered to make them shorter, sexier, more revealing. French fashion was now filling the department stores again, and Hanne bought them each a pair of buckled shoes with small heels from Paris.