The Glimmer Palace (35 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

The woman screamed again and the crowd, suddenly unsure whether it was a stunt after all, began to panic, to disperse and scatter, out of the door and into the rain, trampling onto the stage and knocking over the drum kit. Kurt’s gaze fell on Lilly. At first it was as if he did not recognize her, and then his eyes seemed to focus and harden. He turned back and, with more violence than was necessary, grabbed Hanne’s wrist, pulled her to her feet, and marched her through what was left of the crowd.

That night Hanne lost her other front tooth as well as the shiny new false tooth. Three months later, in March 1920, a right-wing journalist called Kapp staged a military coup supported by Noske’s troops. Ebert’s government evacuated to Dresden and urged the workers of Berlin to stage a general strike. They obliged, and for five days there was no power, no transport, and no water. The city came to a standstill.The putsch collapsed. Noske and his army marched out of Berlin, singing. Hanne and Lilly stood at the window and watched them go. A small boy pointed and laughed at them. One of the soldiers drew out his gun and shot him in the head.

r. Leyer had a glass office. Mr. Leyer had a pile of scripts so high it was said to skim the ceiling, and a huge blackboard that could be extended across his window to block out the sun. Everyone knew him by sight. He was what was kindly termed diminutive but in other words small, with a large head and a habit of saying “Good morning” to everyone and anyone. He liked men, it was rumored, and was not like some of the other producers who held endless closed-door casting sessions from which dozens of would-be actresses would emerge one by one, pink-faced and flustered. So when Lilly had approached him in the corridor and asked if she could introduce him to a friend of hers, a star of cabaret and stage, he had simply nodded, admitted that they were always on the lookout for fresh talent, and carried on walking.

“Just make an appointment,” he had called over his shoulder.

And now Lilly’s lunch break was almost over. She and Hanne had been waiting for thirty minutes. The walls outside Mr. Leyer’s office were covered in stills from the movies he had produced, many of which they recognized: a vampire disappearing into thin air, a pretty girl staring in amazement at a man in a top hat, a judge pronouncing sentence on a prisoner.

His newest movie,

Letters of Love

, was just about to be cast. Lilly had typed up the script herself.

“I am some sort of serving girl and my lover writes me letters,” said Hanne. “Only there is a deranged postman who is in love with me and steals them. My lover comes back, he and the postman fight, my lover dies, and I end up roving the city streets in rags, quite mad.”

“That’s right,” said Lilly. “And then you throw yourself in front of a train, a mail train.”

Hanne smiled. After losing the other front tooth, she had decided to have all her teeth removed and have a set of false teeth fitted. She had read about an American movie star who equated her success with the purchase of dentures. Hanne’s new teeth were porcelain. They were, however, poorly fitted and painful to wear. Her smile faded before it had a chance to hurt.

Ever since Kurt had left the city, Hanne’s moods had veered between wild optimism and torpid depression. Some days she was going to be more famous than Asta Nielsen and Pola Negri put together. On other days she vowed to give up acting completely.

“I’m going to marry a rich old man, settle down, and have two dozen children,” Hanne would say. “You can come and see me on Sundays and take tea. God, I’ll be so boring you won’t believe it.”

“You will never be boring, Hanne,” Lilly said.

“I never want to be poor again,” Hanne replied. “I wish I’d listened to that bank teller. If I’d chosen dollars, I’d be richer than ever now.”

Prices had been rising steadily since the end of the war. Lilly’s pay had been increased twice, but still it didn’t seem to go far enough. Bread had quadrupled in price. Coffee had become completely un-affordable. The Treaty of Versailles decreed that Germany had to pay reparations of two billion gold marks, in installments. Since Germany was virtually bankrupt, the reparations were to be paid in raw materials, in coal, iron, and wood.

Hanne had found a part-time job as an usherette in the Marmorhaus Cinema and managed to pay something toward the rent. It was only temporary, of course, she said. And besides, she could watch all the latest films for nothing. What she needed, she repeated over and over, was a way in, a break, a chance to prove herself.

Mr. Leyer’s secretary had informed them that she had told Mr. Leyer that they were still waiting. Another ten minutes passed. Suddenly, Hanne stood up and began to pull on her coat.

“If I go now, I’ll catch the two-o’clock train back into the city,” Hanne said. “I have to be back for the three-o’clock show anyway.”

Lilly did not knock and she did not apologize. On these two points Mr. Leyer was clear, when he told the story years afterward. As she stepped into the room, the sun momentarily blinded her.

“Mr. Leyer? We can’t wait any longer,” she said.

As her eyes adjusted to the light, she saw not one but four men inside the glass walls of Mr. Leyer’s office. She recognized two. One was the small figure of Mr. Leyer; the other was Ilya Yurasov. They all turned and stared at her.

“Oh, hello,” she said. “I thought . . .”

Ilya greeted her with a small incline of his head. In the letter he had written to her, the letter that the sad-eyed fat girl had lost, he had informed her that he had just been offered a new job. His prewar reputation had eventually caught up with him and he had been plucked from his lowly position as a negative cutter at Afifa and contracted by Deutsche Bioscop, a subsidiary of Ufa. In the letter, he had also explained that he had taken a new apartment, but he had given her his office telephone number and invited her out for lunch. As the weeks and then months had gone by and he had heard nothing from her, at first he had been bemused and then slightly angry and then relieved. He didn’t want to get himself entangled; he didn’t want any complications.

But he could not get her face out of his head. He had often wandered across to the typing pool and in all the frenzied activity had managed to watch her unobserved. He noticed that her typewriter keys stuck and it was he who had arranged for a new machine to be delivered. It was also he who had once found her asleep at her desk on a Saturday and had carried her to a divan and taken off her shoes. He had even mentioned her to his boss, the typing-pool girl who looked not unlike the actress Anya Gregorin, and might be worth considering.

Mr. Leyer, who was constantly being bombarded with casting suggestions by sisters, mothers, taxi drivers, had not bothered to follow up the lead. Ilya knew this and therefore was as surprised as Lilly was when she stepped into the producer’s office unannounced.

“Oh. Anyway, it’s about

Letters of Love

,” she said. “Casting

Letters of Love

, actually.”

Here, Lilly pulled Hanne out of the door frame, where she had been standing, and into the room. Mr. Leyer looked doubly surprised.

“Has the script been sent out already?” said one of the other men.

“No,” Lilly said. “I typed it. I work in the pool.”

“Well,” said Ilya Yurasov, “you must have read a lot of scripts. So, do you like it?”

It did momentarily cross her mind that she wasn’t supposed to admit that she read the work she typed. But Lilly did not pause before answering his question.

“Apart from the unoriginal ending,” she said, “and the tendency to dwell on the melodramatic, it isn’t bad.”

Ilya laughed. His whole face softened. She noticed for the first time the color of his eyes: green—green with flecks of blue. He was in Berlin, after all.The elation she felt within, however, had to be put to one side. She was here for Hanne.

“My point entirely,” he said.

The other men looked slightly dismayed. They were the writers. All four had met that day to discuss the script. Ilya had not been unforthcoming in his criticism.

“So, what do you suggest?” he said.

“Surely,” continued Lilly, “surely in scene thirty-four she needn’t actually pace up and down in front of her mailbox. A look would be enough.”

“A look,” he repeated. “A look?”

Without thinking twice, Lilly demonstrated. She knew how to use her face. The cabaret artist Wernher Siegfried, if nothing else, had been a good teacher.

Ilya nodded. Mr. Leyer nodded. The other two men folded their arms.

“So, what do you suggest for the ending?” Ilya asked.

Lilly glanced from him to Mr. Leyer. The blackboard was covered in writing.

“I really have no idea,” said Lilly. “But since it’s set in a city . . . maybe she throws herself from the top of a new apartment building.”

Mr. Leyer looked at his Russian director.

“The typing-pool girl?”

Ilya nodded.

“Not bad,” said Mr. Leyer. “Not bad at all. But I’ve never heard of any woman doing such a thing.”

Outside, a couple of men were shifting scenery. As they passed, a painted flat of a forest momentarily blocked out the sunlight. At that moment Lilly glanced at Hanne with such a look that the two men could be in no doubt that she did indeed know of a woman who had done such a thing.

“So?” said Lilly. “Will you at least consider . . . ?”

“Indeed I will,” said Mr. Leyer. “I suggest we do a screen test. . . . We could even do it now. We’re casting this afternoon for that Lang film.”

Lilly turned to her friend just as the sun filled the room again. But Hanne wasn’t smiling. Instead, she was staring blank-faced at Lilly, at the short blond hair that she herself had cut and dyed and the large gray eyes accentuated as she had suggested with just a smudge of black. And it seemed as if she suddenly saw her afresh.

“Me?” Lilly replied. “Oh, not me. It’s Hanne you want.”

But it was not.

The Russian

Y

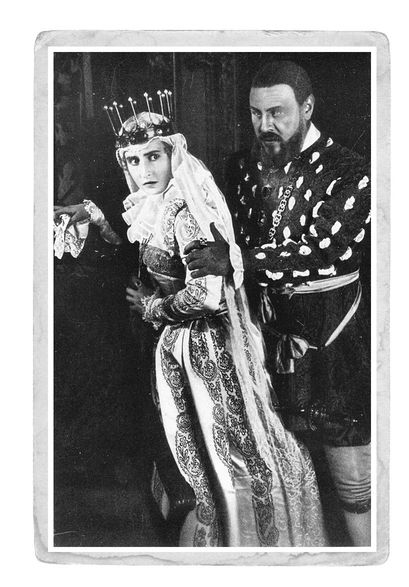

ou are English citizens,” the director tells the crowd through a megaphone. “It is the sixteenth century and you have come to watch the king’s coronation.”

They have hired four thousand extras, but they could have hired double or triple at half the cost. Nobody has a job anymore.Who can live on the government allowance? Everybody’s an actor in Berlin now.

“Action!” the director shouts. “Take one.”

They cheer until they’re hoarse, and then they cheer more, until they’ve reached the nineteenth take without a break. It’s the lighting, somebody says. It’s the acting. It’s Ebert, the president, on an official visit with his entourage. Ebert, the man they voted for but who has done nothing for them; Ebert, the one who cannot stop the strikes and shortages or the misery and the mayhem. From where they stand, it’s possible to watch as he sips a cup of tea and nibbles a sandwich from the catering stand the extras have not been allowed to visit. They start to swarm, wasps in a nest.

“Down with Ebert!” somebody shouts. “Down with Ebert!”

Lubitsch, the director, keeps on filming. He catches their faces, shouting, flushed and furious, until they are on the brink of revolution, on the brink of tearing down his flimsy sets and stringing up the president on the cardboard

flats of Westminster Abbey. And then he cuts. The film company has to abandon its schedule and loses a quarter of a million.The finished film, however, wins an award.

Lilly’s screen test at the Neubabelsberg studio was short and functional. She was told where to stand, her face lit by a bank of lights, and she was asked to look left, look right, look straight into the lens. The script was handed to her and she acted out a scene.

“Have you done this before?” asked Mr. Leyer.

“Not with all my clothes on,” she replied.

Leyer roared with laughter. Lilly barely smiled. And then she returned to the typing pool and stayed late to make up the time that she had missed.

On the way home, she went over and over what had happened that day. By the time she reached the boardinghouse, she had convinced herself that the whole thing was probably an elaborate joke. She would insist that they both go back to Mr. Leyer and try again. And yet, when she thought of the polite Russian and the way he had looked at her, she felt a jolt run straight from the top of her head to the ends of her toes. He hadn’t left Berlin, after all. But why hadn’t he been in touch?

Hanne was standing at the sink wearing nothing but an underslip and her French shoes. She was rubbing cream into her face with short, circular strokes.

“Did you get the part?” said Hanne.

“I don’t know,” said Lilly. “Hanne, I’m so sorry about this afternoon.”

“Why not? That’s what I always say.Why the hell not? If an opportunity comes along, then take it. I know I would.”

Hanne spat on a tablet of kohl and then started to underline her lashes in black with a tiny brush. As she did so, her eyes reddened and her face set, but she kept going, never losing eye contact with herself in the mirror.

“Hanne?” Lilly laid a hand on her shoulder. Hanne turned and stared at it. Lilly removed it.