The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (67 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

George Washington admired European military doctrine. He had begun reading the European authorities while serving as commander of the Virginia militia and soon confirmed their judgments for himself. That books told the truth -- sometimes -- did not surprise him," but his own experience with the militia did, and discouraged him as well. Under arms his fellow Virginians resembled those in civilian life -- stubborn, undisciplined, and lacking in public spirit. Those citizen-soldiers he found in the lines around Cambridge were from New England, but they might have come from Virginia. "Discipline is the soul of an army," the young Washington had written in 1757, and now in 1775 he had to find a way to convert what he considered to be the rabble around Boston into an army. A week after he arrived in Cambridge, he was writing Richard Henry Lee that "The abuses in this army, I fear, are considerable and the new modelling of it, in the face of an enemy, from whom we every hour expect an attack, is exceedingly difficult and dangerous." The weakness of his army, he believed, was inherent in any nonprofessional force -- its members, officers and men alike, had interests and ties which could not be reconciled with the purposes of a professional army. To a certain extent then, a militia would always remain unreliable simply

____________________

42 | Saxe and Frederick the Great were cited by both British and American writers. |

because of what it was, a collection of civilians on temporary duty.

43

Washington, a Virginian with the conventional prejudices of the eighteenth-century breed, detected still another sort of weakness in the New England army. Its soldiers were for the most part from Massachusetts, a colony well known in Virginia for its leveling democracy, and democrats did not make good soldiers. Washington found "an unaccountable kind of stupidity in the lower class of these people," which "prevails but too generally among the officers of the Massachusetts part of the Army who are nearly all the same kidney with the Privates."

44

Unaccountable as this "stupidity" may have seemed, Washington felt quite able to account for it as the inevitable result of equality. The Massachusetts privates elected their officers, with predictable consequences for their ability to command: "there is no such thing as getting of officers of this stamp to exert themselves in carrying orders into execution -- to curry favor with the men (by whom they were chosen, and on whose smiles possibly they may think they may again rely) seems to be one of the principal objects of their attention."

45

Although Washington had a clear conception of the kind of army he wanted, he was not so wedded to traditional European ideas as to be incapable of making do with what he had. At Cambridge in 1775 and throughout the war, though he strove to create a conventional army, he proved himself capable of departing from standard doctrine. He campaigned in the winter; he used irregulars -- as the militias surely were; he appealed to political principles and to the nation; and he did not attempt to confine the war to a few men of his class and to the dregs of society.

Washington's first acts in Cambridge revealed the practical intelligence that served him so well. The day after his arrival he asked for a return of information on the numbers of troops in the army and the gunpowder on hand. The week that elapsed before this simple accounting could be made gave him pause and more than a hint of how badly the army was organized and administered. Nor were the answers that finally came encouraging: the army numbered 16,600 enlisted men and noncommissioned officers, of whom not quite 14,000 were present and fit for duty. Washington believed that he needed over 20,000 men for the siege; the British, he thought, had 11,500, and of course the British controlled

____________________

43 | GW Writings |

44 | Ibid., |

45 | Ibid., |

the waters around Boston, and this control meant that they could concentrate their forces.

46

The next step was to take a look at the lines. This reconnoitering took two days -- not because the Americans were deeply entrenched in well-chosen positions, but because they were not. There were shallow redoubts on Winter Hill and Prospect Hill, on the north, overlooking the Charlestown peninsula; a crude abatis on the Boston Road and a trench across Roxbury's main street, presumably blocking Boston Neck; and a breastwork on Dorchester Road near the burying ground to the southeast. Dorchester Heights, which dominated Boston and the approaches from the sea, had not been occupied by either side. None of this provided reassurance to an anxious Washington, who almost immediately laid out new lines for fortifications.

If Washington were to conduct operations against the British in Boston and eventually drive them out, he had simultaneously to train an army. To train this army to besiege a city did not entail instruction in tactics -in how, for example, to wheel in columns of battalions or how to move from line of march to line of assault. Washington might have wished at times that he could afford such luxuries in training, but he could not even take the time to exercise his soldiers in siege operations. Training had to be conducted on a much simpler -- indeed primitive -- level. Training these men involved disciplining them, getting them to take orders and to do the simplest tasks without the shirking and slovenly behavior they were accustomed to. They slept away from their camps and entrenchments, apparently with the approval of their officers; those on guard left their posts before they were relieved; some crept out beyond the line of sentries to take long-distance shots at the British, a practice which made Washington writhe in embarrassment and shame; sentries and their officers talked with the enemy along the outpost lines. Furloughs were granted easily and in defiance of common prudence which required that units be kept at maximum strength; the camps themselves were filthy, latrines improperly placed and irregularly covered over after extensive use. Junior officers failed to inspect their men, neglecting what should have been first among their responsibilities -- supervision of food and quarters.

47

____________________

46 | Freeman, |

47 | Ibid., |

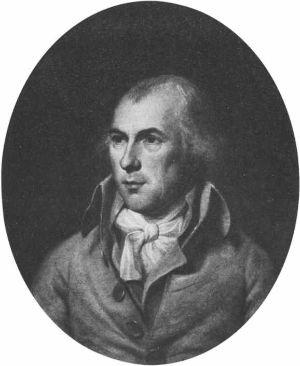

George Washington, after a miniature by Charles Willson Peale

Mount Vernon Ladies Association