The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (68 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

In a conventional army the commanding general did not have to concern himself with such matters, properly the concern of sergeants and lieutenants. Washington had few officers worthy of the name, and hence his general orders issued on a daily basis were filled with details about matters which should have been reserved for noncommissioned and junior officers. All betray two related concerns. The welfare of the troops: the quartermaster general is to investigate complaints that the bread is "sour and unwholesome"; company officers are to inspect the men's food and the camp kitchens; the men should have clean straw for their bedding; "the necessaries to be filled up once a week, and new ones dug; the Streets of the encampments and Lines to be swept daily, and all offal and Carrion, near the camp, to be immediately burned." The discipline of the men and the standards of performance were also much in Washington's orders. Hence he informed his soldiers immediately that with his command they were now under Congress as the Troops of the UNITED PROVINCES of North America, that since they were fighting for their liberty much was expected of them. They should refrain from "profane cursing, swearing and drunkenness"; they should know that he required "punctual attendance on divine Service, to implore the blessings of heaven upon the means used for our safety and defense." A flood of orders followed forbidding waste of powder, talking with the enemy, and slovenly standing of the guard and requiring company officers to crack down on unsoldierlike practices. Lest there be doubt about how seriously Washington took these common affairs, he convened courts-martial to drive home the point. Drumming out, cashiering of officers, fines and lashes followed With a grim regularity. The officers who allowed their troops free rein were soon departing the camps in disgrace as Washington "made a pretty good slam" among them, a phrase he used which reveals the anger he felt toward dereliction.

48

While Washington strove to create an army from the free spirits of the militia, operations had to be conducted against the British. Diggingin commenced at once all along the line. The British were doing the same thing, and the two sides watched one another warily. By the end of August the American fortifications were virtually complete, and Washington soon after proposed an assault up the Neck from Roxbury and by boats across the bay, an idea the council of war he convened disapproved, Washington yielded to this group, believing that he was bound

____________________

48 | GW Writings |

by congressional instruction not to act without the approval of his senior officers. It was the first instance of several in which his regard for civilian authority and the advice of others inhibited action.

By early fall one treacherous problem had been solved -- the shortage of powder -- but another beckoned, a shortage of troops which would commence when the enlistments of those from Connecticut and Rhode Island expired in December and January.

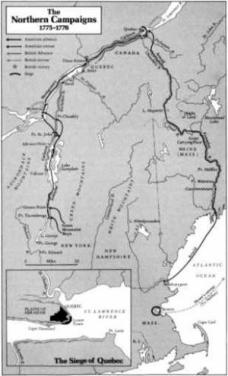

Even as Washington directed operations around Boston, he planned action against Canada in accordance with the wishes of Congress. Deciphering those wishes was no easy task in the early summer. For Congress did not make up its mind about an expedition until late June when it ordered Major General Philip Schuyler to take Canada if he found doing so "practicable" and not "disagreeable" to the Canadians. By far the largest number of Canadians were of French origin, and Congress may have doubted whether this group shared American principles.

While Schuyler prepared in western New York, Washington set Benedict Arnold in motion from Massachusetts. Arnold spent late August and early September collecting men and supplies and planned an expedition that would follow the rivers of Maine to Quebec. Arnold believed that in twenty days he would be demanding surrender from Sir Guy Carleton, the British general who served as governor of Canada. Arnold's optimism was equaled only by his ignorance of the geography of the Northeast -- he thought that he had only 180 miles to travel; in reality he had 350 that would take him forty-five days to cover.

Soon after setting out Arnold was forced to recognize that reaching Quebec would strain his men's bodies and spirits. During the first three weeks of his march into the Maine wilderness, he seems to have believed that his men could do anything. They sailed from Newburyport to the mouth of the Kennebec, a distance of 150 miles, on September 19. The river was wide enough and deep enough to accommodate their ships which reached Gardinerstown three days later. There most of the troops either embarked in bateaux, small boats capable of carrying six or seven men and provisions, or marched along the river's edge. A few of the troops remained in the smaller sailing vessels until the narrowness of the river compelled them to join the others on land.

The expedition forced its way up the river to the Great Carrying Place, a portage of twelve miles, by October 11. Long before reaching it, the boats began to leak and, according to Arnold, a "great part" of

the bread was ruined. To add to their food supply, the men fished for trout in several ponds at this portage and caught as many as "ten dozen" in an hour. Carrying the boats for twelve miles left arms and legs and backs aching -- each bateau weighed 400 pounds, and arms, ammunition, and provisions had to be carried too. Spirit remained high, Arnold reported, despite pain and fatigue.

The remainder of the march was even more difficult, so difficult in fact that the expedition almost collapsed. From the Great Carrying Place, the troops entered the Dead River. Perhaps no stream in America was so badly named. The Dead River was alive with a ferocious current and snags of sunken logs and brush that slowed and sometimes stopped all progress. The men had spent so much time in the water -- and under it -- while going up the Kennebec that Arnold likened them to "amphibious animals." Now they were constantly wet, especially after October 19 when a heavy rain which lasted for three days sent the river over its banks. Still they dragged themselves along, often with little or nothing to eat.

Near the end of October most of the expedition had covered the thirty miles of the Dead River to the Height of Land -- the watershed between the Kennebec and the Chaudière rivers. By this time many of the men were sick. They had been half-frozen for days -- snow had fallen -- and they were in need of food, clothing, and shoes. And they still had to cross Lake Megantic and from there sail down the Chaudière River to the St. Lawrence. On November 9, these desperately tired men made it to the St. Lawrence River. By this time they numbered 675; some 300 had turned back, others had been left sick or dead along the way.

The expedition found itself four miles from Quebec and of course across the river from it. A heavy storm stopped them from crossing until November 13; almost nothing else could have delayed Arnold, for after the misery of the march he craved battle. He did not get it until the end of December.

Quebec boasted no formidable garrison, but it could not be taken by the sick and badly equipped force Arnold commanded. The city sat on a high point of land cut out by the St. Lawrence and its tributary the St. Charles River. This point -- it actually resembles a swollen thumb or several fingers pressed tightly together -- looks to the northeast. On the 3southeastern side, Cape Diamond rises more than 300 feet above the St. Lawrence River. Along the St. Charles, to the northwest, the land slopes downward.

Slightly to the northeast of Cape Diamond, Lower

Town huddled along the narrow band of land on the water's edge. At its southern side fortifications had been built, two rough palisades and a blockhouse. There was also a wall at the northern part of the Lower Town and outside it small clusters of suburbs.

The main part of the city, Upper Town, stood astride the high ground, protected by its height, the steep cliffs on three sides, and to the west by a wall thirty feet high which extended from river to river. The wall looked toward the Plains of Abraham, where Wolfe and Montcalm had fought and died. There were six strong points along the wall and three gates. Quebec's defenders concentrated their artillery at the six strong places. Within Upper Town the British assembled about 1800 troops, a strange mixture of militia, Scottish soldiers, a handful of marines, and large numbers of sailors drawn from ships in the harbor.

Arnold's force made a brave show in front of the wall for a few days and then pulled back twenty miles to Pointe aux Trembles. There early in December, Richard Montgomery, Schuyler's second-in-command in western New York, joined them. Montgomery, an attractive man in every respect, as handsome and brave as the most splendid heroes of eighteenth-century romances, had fought his way to Montreal which fell to his forces in November. He had then led his soldiers, some 300 in all, carrying provisions, heavy winter clothing, cannon, and ammunition to where Arnold's men lay suffering. Arnold greeted Montgomery with joy, and in about three weeks the two were prepared to assault Quebec.