Authors: Pearl S. Buck

The Good Earth (41 page)

His sons were proper enough to him and they came to him every day or at most once in two days, and they sent him delicate food fit for his age, but he liked best to have one stir up meal in hot water and sup it as his father had done.

Sometimes he complained a little of his sons if they came not every day and he said to Pear Blossom, who was always near him,

“Well, and what are they so busy about?”

But if Pear Blossom said, “They are in the prime of life and now they have many affairs. Your eldest son has been made an officer in the town among the rich men, and he has a new wife, and your second son is setting up a great grain market for himself,” Wang Lung listened to her, but he could not comprehend all this and he forgot it as soon as he looked out over his land.

But one day he saw clearly for a little while. It was a day on which his two sons had come and after they had greeted him courteously they went out and they walked about the house on to the land. Now Wang Lung followed them silently, and they stood, and he came up to them slowly, and they did not hear the sound of his footsteps nor the sound of his staff on the soft earth, and Wang Lung heard his second son say in his mincing voice,

“This field we will sell and this one, and we will divide the money between us evenly. Your share I will borrow at good interest, for now with the railroad straight through I can ship rice to the sea and I …”

But the old man heard only these words, “sell the land,” and he cried out and he could not keep his voice from breaking and trembling with his anger,

“Now, evil, idle sons—sell the land!” He choked and would have fallen, and they caught him and held him up, and he began to weep.

Then they soothed him and they said, soothing him,

“No—no—we will never sell the land—”

“It is the end of a family—when they begin to sell the land,” he said brokenly. “Out of the land we came and into it we must go—and if you will hold your land you can live—no one can rob you of land—”

And the old man let his scanty tears dry upon his cheeks and they made salty stains there. And he stooped and took up a handful of the soil and he held it and he muttered,

“If you sell the land, it is the end.”

And his two sons held him, one on either side, each holding his arm, and he held tight in his hand the warm loose earth. And they soothed him and they said over and over, the elder son and the second son,

“Rest assured, our father, rest assured. The land is not to be sold.”

But over the old man’s head they looked at each other and smiled.

Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973) was a bestselling and Nobel Prize-winning author of fiction and nonfiction, celebrated by critics and readers alike for her groundbreaking depictions of rural life in China. Her renowned novel

The Good Earth

(1931) received the Pulitzer Prize and the William Dean Howells Medal. For her body of work, Buck was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Literature—the first American woman to have won this honor.

Born in 1892 in Hillsboro, West Virginia, Buck spent much of the first forty years of her life in China. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries based in Zhenjiang, she grew up speaking both English and the local Chinese dialect, and was sometimes referred to by her Chinese name, Sai Zhenzhju. Though she moved to the United States to attend Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, she returned to China afterwards to care for her ill mother. In 1917 she married her first husband, John Lossing Buck. The couple moved to a small town in Anhui Province, later relocating to Nanking, where they lived for thirteen years.

Buck began writing in the 1920s, and published her first novel,

East Wind: West Wind

in 1930. The next year she published her second book,

The Good Earth

, a multimillion-copy bestseller later made into a feature film. The book was the first of the Good Earth trilogy, followed by

Sons

(1933) and

A House Divided

(1935). These landmark works have been credited with arousing Western sympathies for China—and antagonism toward Japan—on the eve of World War II.

Buck published several other novels in the following years, including many that dealt with the Chinese Cultural Revolution and other aspects of the rapidly changing country. As an American who had been raised in China, and who had been affected by both the Boxer Rebellion and the 1927 Nanking Incident, she was welcomed as a sympathetic and knowledgeable voice of a culture that was much misunderstood in the West at the time. Her works did not treat China alone, however; she also set her stories in Korea (

Living Reed

), Burma (

The Promise

), and Japan (

The Big Wave

). Buck’s fiction explored the many differences between East and West, tradition and modernity, and frequently centered on the hardships of impoverished people during times of social upheaval.

In 1934 Buck left China for the United States in order to escape political instability and also to be near her daughter, Carol, who had been institutionalized in New Jersey with a rare and severe type of mental retardation. Buck divorced in 1935, and then married her publisher at the John Day Company, Richard Walsh. Their relationship is thought to have helped foster Buck’s volume of work, which was prodigious by any standard.

Buck also supported various humanitarian causes throughout her life. These included women’s and civil rights, as well as the treatment of the disabled. In 1950, she published a memoir,

The Child Who Never Grew

, about her life with Carol; this candid account helped break the social taboo on discussing learning disabilities. In response to the practices that rendered mixed-raced children unadoptable—in particular, orphans who had already been victimized by war—she founded Welcome House in 1949, the first international, interracial adoption agency in the United States. Pearl S. Buck International, the overseeing nonprofit organization, addresses children’s issues in Asia.

Buck died of lung cancer in Vermont in 1973. Though

The Good Earth

was a massive success in America, the Chinese government objected to Buck’s stark portrayal of the country’s rural poverty and, in 1972, banned Buck from returning to the country. Despite this, she is still greatly considered to have been “a friend of the Chinese people,” in the words of China’s first premier, Zhou Enlai. Her former house in Zhenjiang is now a museum in honor of her legacy.

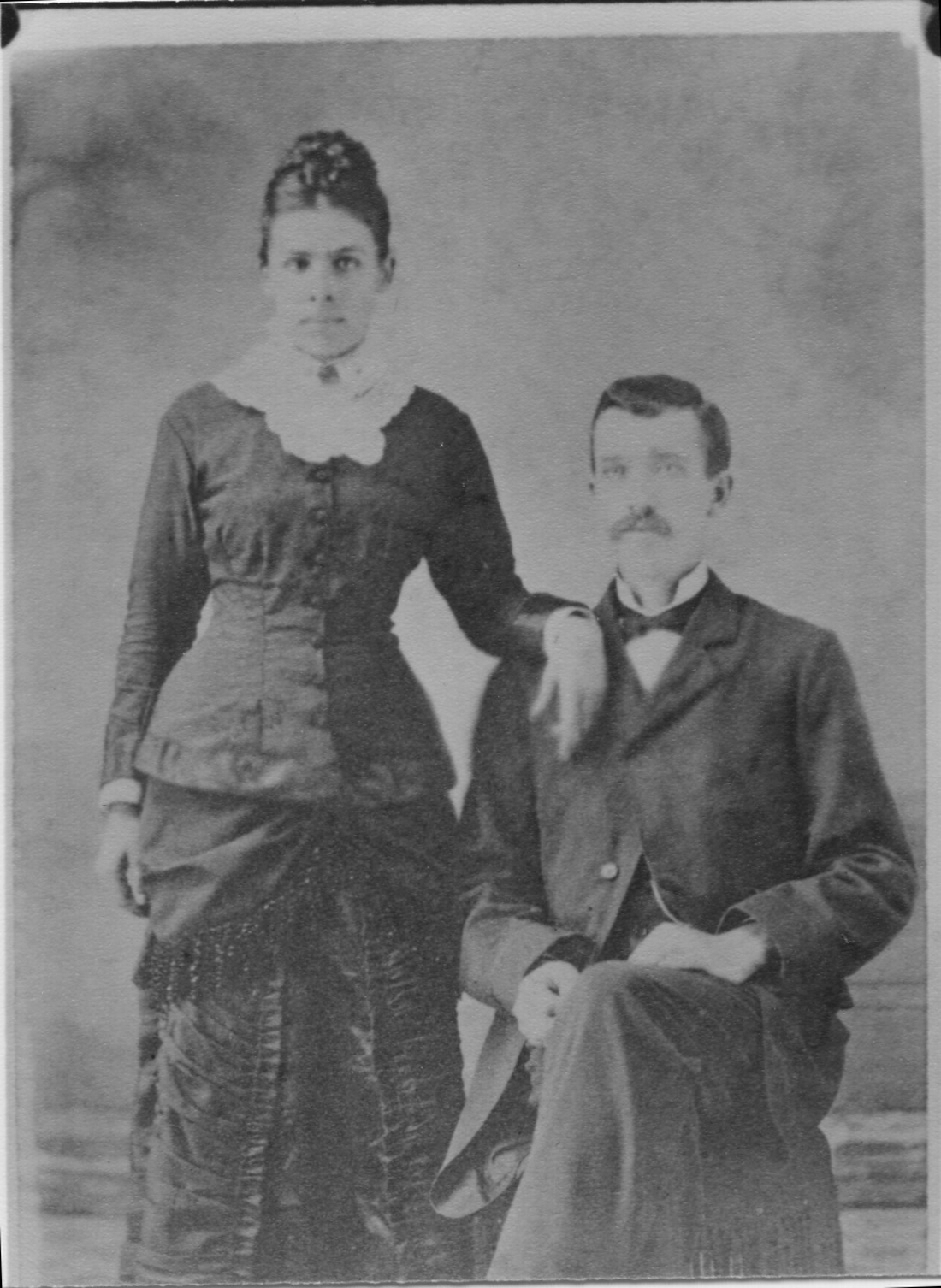

Buck’s parents, Caroline Stulting and Absalom Sydenstricker, were Southern Presbyterian missionaries.

Buck was born Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker in Hillsboro, West Virginia, on June 26, 1892. This was the family’s home when she was born, though her parents returned to China with the infant Pearl three months after her birth.

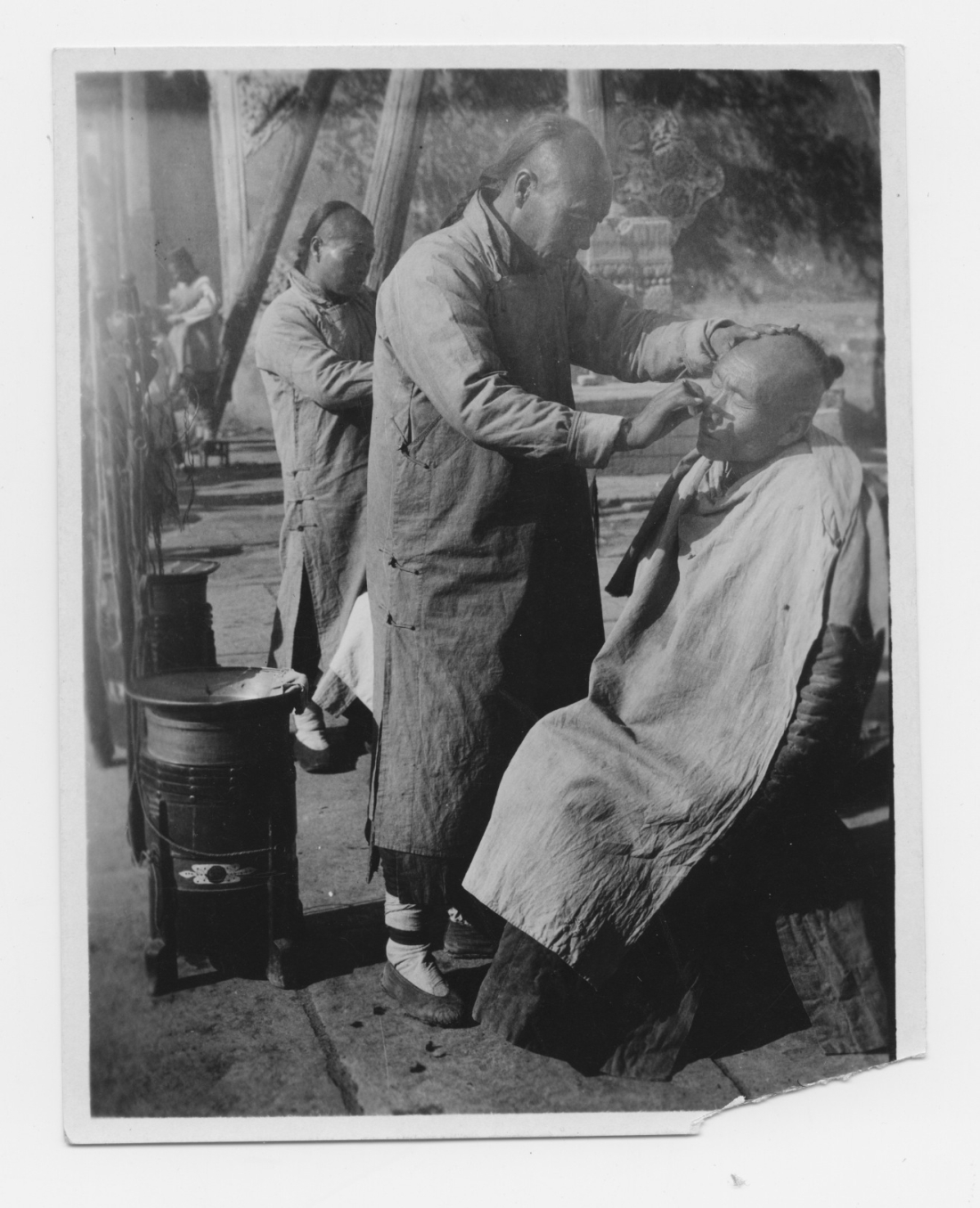

Buck lived in Zhenjiang, China, until 1911. This photograph was found in her archives with the following caption typed on the reverse: “One of the favorite locations for the street barber of China is a temple court or the open space just outside the gate. Here the swinging shop strung on a shoulder pole may be set up, and business briskly carried on. A shave costs five cents, and if you wish to have your queue combed and braided you will be out at least a dime. The implements, needless to say, are primitive. No safety razor has yet become popular in China. Old horseshoes and scrap iron form one of China’s significant importations, and these are melted up and made over into scissors and razors, and similar articles. Neither is sanitation a feature of a shave in China. But then, cleanliness is not a feature of anything in the ex-Celestial Empire.”

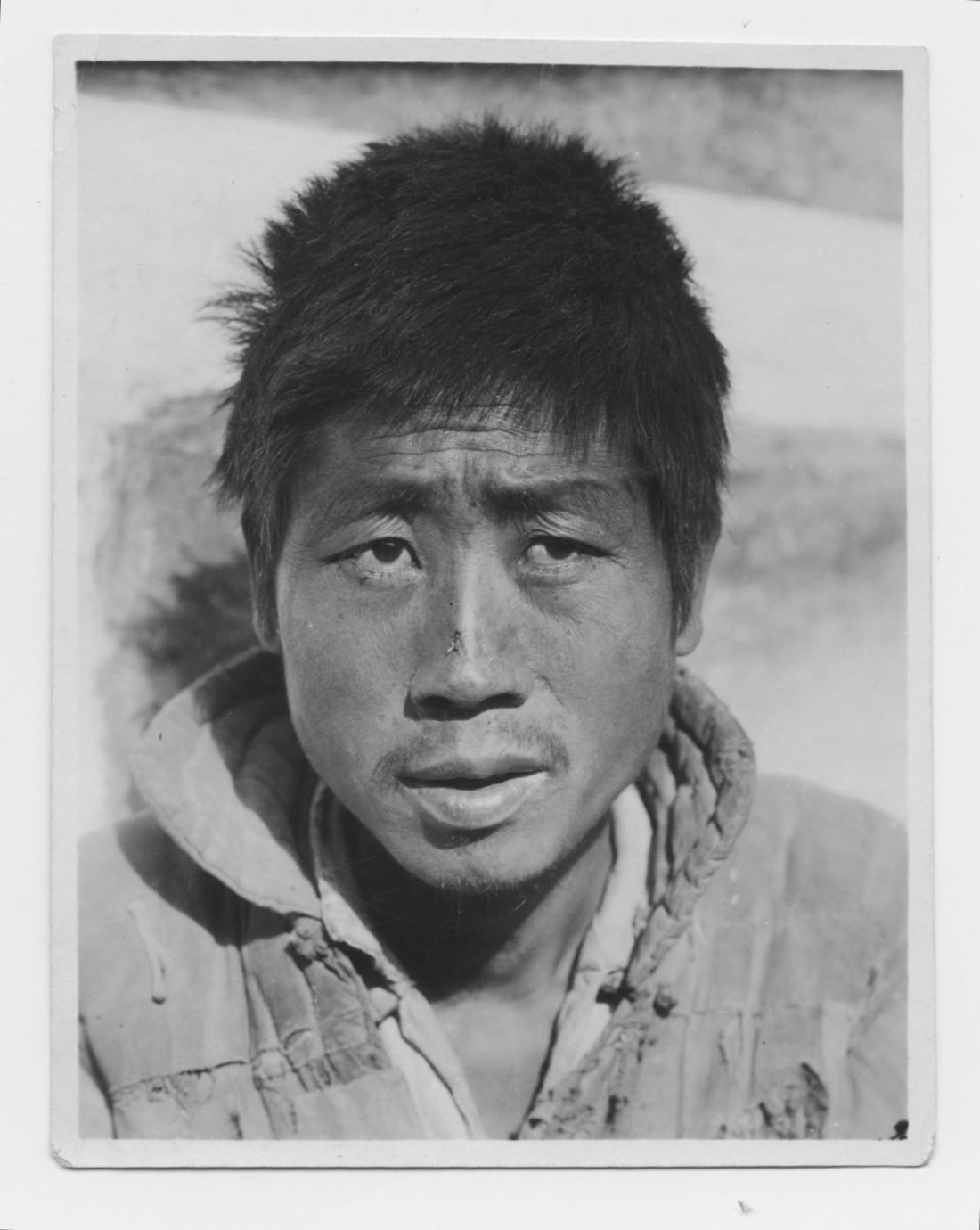

Buck’s writing was notable for its sensitivity to the rural farming class, which she came to know during her childhood in China. The following caption was found typed on the reverse of this photograph in Buck’s archive: “Chinese beggars are all ages of both sexes. They run after your rickshaw, clog your progress in front of every public place such as a temple or deserted palace or fair, and pester you for coppers with a beggar song—‘Do good, be merciful.’ It is the Chinese rather than the foreigners who support this vast horde of indigent people. The beggars have a guild and make it very unpleasant for the merchants. If a stipulated tax is not paid them by the merchant they infest his place and make business impossible. The only work beggars ever perform is marching in funeral and wedding processions. It is said that every family expects 1 or 2 of its children to contribute to support of family by begging.”

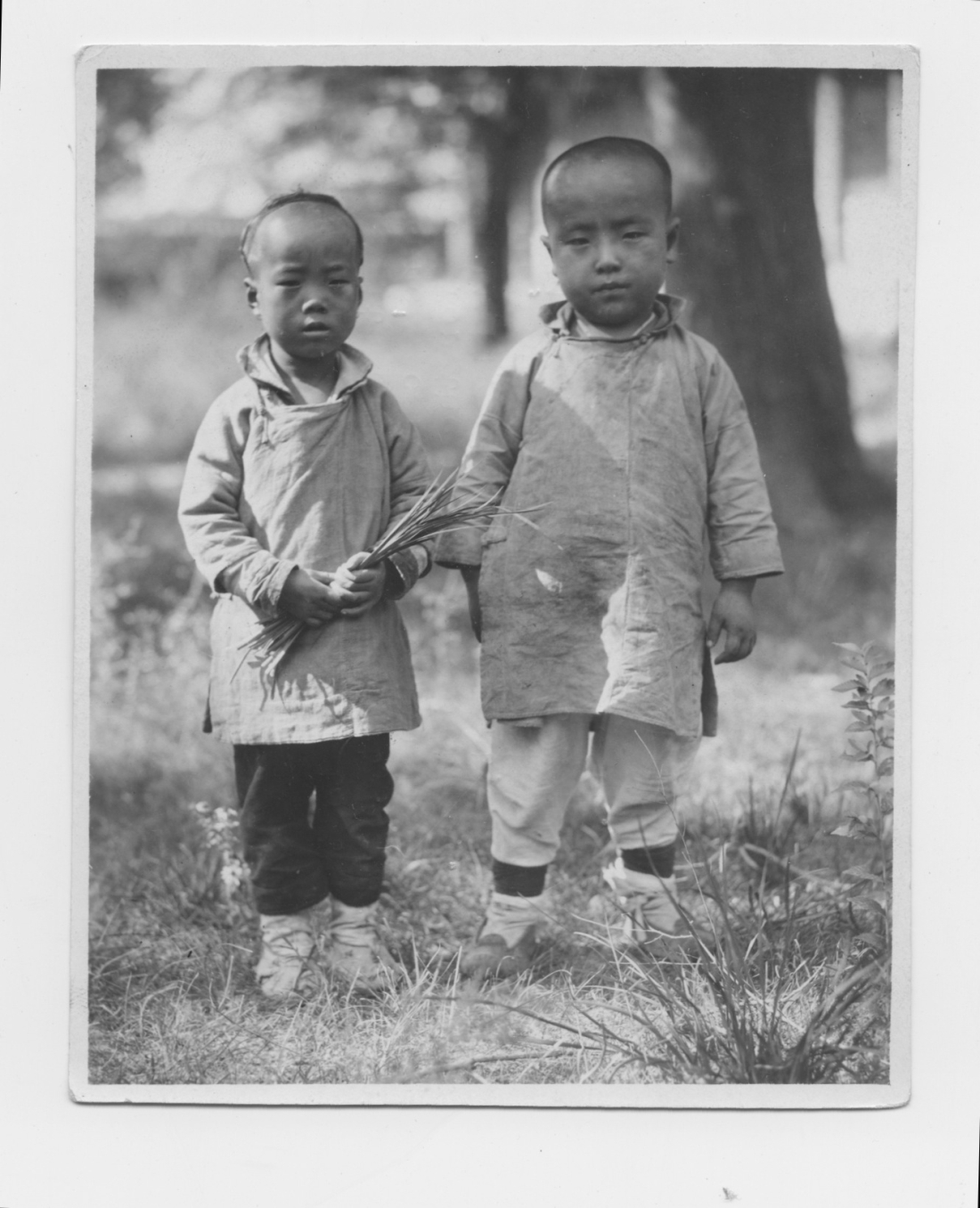

Buck worked continually on behalf of underprivileged children, especially in the country where she grew up. The following caption was found typed on the reverse of this photograph in Buck’s archive: “The children of China seem to thrive in spite of dirt and poverty, and represent nature’s careful selection in the hard race for the right to existence. They are peculiarly sturdy and alert, taken as a whole, and indicate something of the virility of a nation that has continued great for four thousand years.”

Johann Waldemar de Rehling Quistgaard painted Buck in 1933, when the writer was forty-one years old—a year after she won the Pulitzer Prize for

The Good Earth

. The portrait currently hangs at Green Hills Farm in Pennsylvania, where Buck lived from 1934 and which is today the headquarters for Pearl S. Buck International. (Image courtesy of Pearl S. Buck International,

www.pearlsbuck.org

.)