The Grand Alliance (87 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

The Grand Alliance

532

4

The Atlantic Charter

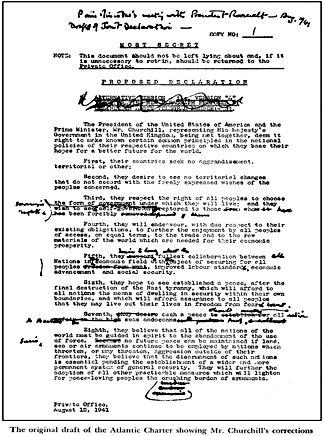

My Original Draft of the Atlantic Charter — President Roosevelt’s Proposed Alterations — Our

Discussions of August

11 —

Need to Safeguard

Imperial Preference — My Reports of August

11

to the Foreign Office and the Cabinet — The

Cabinet’s Prompt Reply — The Atlantic Islands —

Our Agreement About Policy Towards Japan —

Final Form of the Atlantic Charter — A Joint Anglo-American Message to Stalin — My Memorandum

About American Supplies — Mr. Purvis Killed in a

Plane Accident — Report of August

12

to the

Cabinet — Congratulations from the King and

Cabinet — Report to Australian Prime Minister —

Voyage to Iceland — I Return to London, August

19.

P

RESIDENT ROOSEVELT told me at one of our first conversations that he thought it would be well if we could draw up a joint declaration laying down certain broad principles which should guide our policies along the same road. Wishing to follow up this most helpful suggestion, I gave him the next day, August 10, a tentative outline of such a declaration. My text was as follows: JOINT ANGLO-AMERICAN DECLARATION OF

PRINCIPLES

The President of the United States of America and the Prime Minister, Mr. Churchill, representing His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom, being The Grand Alliance

533

met together to resolve and concert the means of providing for the safety of their respective countries in face of Nazi and German aggression and of the dangers to all peoples arising therefrom, deem it right to make known certain principles which they both accept for guidance in the framing of their policy and on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world.

First, their countries seek no aggrandisement, territorial or other.

Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned.

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live. They are only concerned to defend the rights of freedom of speech and thought, without which such choice must be illusory.

Fourth, they will strive to bring about a fair and equitable distribution of essential produce, not only within their territorial boundaries, but between the nations of the world.

Fifth, they seek a peace which will not only cast down for ever the Nazi tyranny, but by effective international organisation will afford to all States and peoples the means of dwelling in security within their own bounds and of traversing the seas and oceans without fear of lawless assault or the need of maintaining burdensome armaments.

Considering all the tales of my reactionary, Old-World outlook, and the pain this is said to have caused the President, I am glad it should be on record that the substance and spirit of what came to be called the “Atlantic Charter” was in its first draft a British production cast in my own words.

August 11 promised to be a day of intense business.

The Grand Alliance

534

Prime

Minister

to

11 Aug. 41

Admiralty

Utmost strength to be put on deciphering telegrams

from here during next twenty-four hours.

At our meeting in the morning the President gave me a revised draft, which we took as a basis for discussion. The only serious difference from what I had written was about the fourth point (access to raw materials). The President wished to insert the words, “without discrimination and on equal terms.” The President also proposed two extra paragraphs.

Sixth, they desire such a peace to establish for all safety on the high seas and oceans.

The Grand Alliance

535

Seventh, they believe that all the nations of the world must be guided in spirit to the abandonment of the use of force. Because no future peace can be maintained if land, sea, or air armaments continue to The Grand Alliance

536

be employed by nations which threaten, or may threaten, to use force outside of their frontiers, they believe that the disarmament of such nations is essential. They will further the adoption of all other practicable measures which will lighten for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments.

Before we discussed this document, the President explained that his idea was that there should be issued simultaneously in Washington and London, perhaps on August 14, a short statement to the effect that the President and the Prime Minister had held conversations at sea; that they had been accompanied by members of their respective staffs; that the latter had discussed the working-out of aid to the democracies under the Lend-Lease Act; and that these naval and military conversations had in no way been concerned with future commitments other than as authorised by Act of Congress. The statement would proceed to say that the Prime Minister and the President had discussed certain principles relating to the civilisation of the world and had agreed on a statement of them. I deprecated the emphasis which a statement on these lines would lay on the absence of commitments. This would be seized on by Germany and would be a source of profound discouragement to the neutrals and to the vanquished. We also would not like it. I very much hoped therefore that the President could confine the statement to the positive portion which dealt with the question of aid to the democracies, more especially as he had guarded himself by the reference to the Lend-Lease Act. The President accepted this.

There followed a detailed discussion of the revised text of the declaration. Several minor alterations were easily agreed. The chief difficulties were presented by Points 4

and 7, especially the former. With regard to this, I pointed

The Grand Alliance

537

out at once that the words “without discrimination” might be held to call in question the Ottawa Agreements, and I was in no position to accept them. This text would certainly have to be referred to the Government at home, and, if it was desired to maintain the present wording, to the Governments in the Dominions. I should have little hope that it would be accepted. Mr. Sumner Welles indicated that this was the core of the matter, and that this paragraph embodied the ideal for which the State Department had striven for the past nine years. I could not help mentioning the British experience in adhering to free trade for eighty years in the face of ever-mounting American tariffs. We had allowed the fullest importations into all our colonies. Even our coastwise traffic around Great Britain was open to the competition of the world. All we had got in reciprocation was successive doses of American Protection. Mr. Welles seemed to be a little taken aback. I then said that if the words, “with due respect for their existing obligations,” could be inserted, and if the words, “without discrimination,” could disappear, and “trade” be substituted for “markets,” I should be able to refer the text to His Majesty’s Government with some hope that they would be able to accept it. The President was obviously impressed. He never pressed the point again.

As regards the generalities of Point 7, I pointed out that while I accepted this text, opinion in England would be disappointed at the absence of any intention to establish an international organisation for keeping peace after the war. I promised to try to find a suitable modification, and later in the day I suggested to the President the addition to the second sentence of the words, “pending the establishment of a wider and more permanent system of general security.”

The Grand Alliance

538

Continuous conferences also took place between the naval and military chiefs, and a wide measure of agreement was reached between them. I had outlined to the President the dangers of a German incursion into the Iberian Peninsula, and explained our plans for occupying the Canary Islands –

known as Operation “Pilgrim” – for countering such a move.

I then sent to Mr. Eden a summary of this discussion.

Prime

Minister

to

11 Aug. 41

Foreign Office

The President has received a letter from Doctor

Salazar, in which it is made clear that he is looking to

the Azores as a place of retreat for himself and his

Government in the event of German aggression upon

Portugal, and that his country’s age-long alliance with

England leads him to count on British protection during

his enforced stay in these islands.

2. If however the British were too much occupied

elsewhere, he would be willing to accept assistance

from the United States instead. The President would be

well disposed to respond to such an appeal, and would

like the British in the circumstances foreseen to

propose to Doctor Salazar the transference of responsibility. The above would also apply to the Cape Verdes.

3. I told the President that we contemplate the

operation known as “Pilgrim”; that we might be forced

to act before a German violation of the peninsula had

occurred, and that while this was going on we should

be very busy. I pointed out that “Pilgrim” would almost,

though not absolutely certainly, provoke a crisis in the

peninsula, and asked whether our having set events in

train by “Pilgrim” would be any bar to his acceptance of

the responsibility indicated in paragraph 1. He replied

that as “Pilgrim” did not affect Portugal, it made no

difference to his action.

4. He would feel justified in taking action if the

Portuguese islands were endangered, and we agreed

that they would certainly be endangered if “Pilgrim”

The Grand Alliance

539

were to take place, as the Germans would have all the

more need to forestall us there.

5. In these circumstances he would none the less be

ready to come to the aid of Portugal in the Atlantic

islands, and was holding strong forces available for that

purpose.

I have shown foregoing to President, who agreed

that it was a correct representation of the facts.

We then, on the same day, turned to the Far East. The imposition of the economic sanctions on July 26 had caused a shock in Tokyo. It had not perhaps been realised by any of us how powerful they were. Prince Konoye sought at once to renew diplomatic talks, and on August 6 Admiral Nomura, the Japanese Special Envoy in Washington, presented to the State Department a proposal for a general settlement. Japan would undertake not to advance farther into Southeast Asia, and offered to evacuate Indo-China on the settlement of “the China incident.” (Such was the term by which they described their six-years war upon China.) In return the United States were to renew trade relations and help Japan to obtain all the raw materials she required from the Southwest Pacific. It was obvious that these were smoothly worded offers by which Japan would take all she could for the moment and give nothing for the future. No doubt they were the best Konoye could procure from his Cabinet. Around our conference table on the

Augusta

there was no need to argue the broad issues. My telegram sent from the meeting to Mr. Eden gives a full account of the matter: