The Grand Ole Opry (21 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

Dollie Dearman. Early in her career, Dollie had been a dancer with Roy Acuff and Minnie Pearl, and she entertained the troops

on USO tours. After the war, she worked for the Grand Ole Opry selling songbooks.

Harry Stone left WSM in August 1950 and, in January the following year, moved to KPHO in Phoenix, Arizona. Jim Denny and Jack

Stapp now ran the Opry, but Jack DeWitt was determined to keep Denny on a short leash.

In the late 1930s, when Ira and Charlie Louvin saw Roy Acuff near their hometown in northern Alabama, they were already perfecting

the unerring sibling harmony that later influenced Emmylou Harris, the Everly Brothers, and many others. Working at various

radio stations throughout the mid-South, their goal was always to join Acuff on the Grand Ole Opry.

CHARLIE LOUVIN:

We had a neighbor a mile away that had a radio. He owned a grocery store, and there were pretty good crowds in his living

room on Saturday night, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five people, just to listen to the Opry. We’d stay until he’d say it’s goin’

home time, and someone ran us off. Mr. Acuff came to our neighborhood. It was the first year he came to the Opry. He was drivin’

that car. Block and a half long. It was an air-cooled Franklin. Three doors on each side. There was places he had trouble

going ’cause the car almost needed hinges to make the curve. It was ten cents for kids and twenty cents or a quarter for adults.

We didn’t have no money to get in, but it was warm weather and they had the windows up so we heard and seen the show as good

as anybody. It looked like a good life. I was twelve years old, and from that point we earnestly prepared ourselves to be

on the Opry.

Ten years later, Ira and Charlie decided it was time for them, too, to be Opry stars. Charlie Louvin’s story of how hard it

was to get on the Opry proves how crucial Opry membership had become.

The Louvin Brothers treat the audience to some of their close harmony singing on the Prince Albert Opry.

CHARLIE LOUVIN:

We were working Memphis, and every time we’d have a day off on the weekend we’d come to the Opry. We’d corral Jim Denny in

what was known as the tool shed at the Ryman. We’d take him in there and sing him a song. We got that “Don’t call us, we’ll

call you” for years. It got rough after I got back from Korea, so we called Ken Nelson at Capitol Records and said, “Do you

know anybody at the Opry?” He said, “Well, I’m pretty good friends with Jack Stapp.” I said, “Well, Ira and I, we decided

that we’re gonna quit the business if we can’t get on the Opry.” ’Cause we just weren’t makin’ a living, you see. I was on

the street at a payphone. Ken Nelson called Mister Stapp and told him he had a duet that was on his label, and he’d like to

have ’em on the Opry. Evidently, Mister Stapp give him a discouraging message, and Mister Nelson said, “Well, if you don’t

want ’em, the Ozark Jubilee does.” And Mister Stapp said, “Now, wait a minute, we don’t want no more people going up to the

Ozark Jubilee. Tell ’em to show up this Friday.” So we went up and we were introduced to Vito Pellettieri and Jack Stapp,

and we were taken to Mister Denny’s office. He totally ignored us for ten minutes. He talked to everybody in town that his

secretary could find. Finally, my brother, who had a much shorter fuse than me, said, “Well, Mister Denny, we’ll see you tonight

on the Grand Ole Opry.” Mister Denny pulled his half-glasses down to the end of his nose and looked up over what he wasn’t

busy at, and said, “Boys, you’re in tall timber. You’d better shit and git it.” My brother looked him in the eye and said,

“We got the saws. Jus’ show us where the woods are.”

The Grand Ole Opry was not only drawing the top country stars to Nashville; it was drawing the music business in their wake.

Record producers knew that their artists would be there on the weekend; song plug-gers knew that the record producers would

be in town; and bookers knew that they could pitch show dates to artists’ managers. Many of the deals were done backstage

at the Opry, or in the alley beside the Opry, or at what is now Tootsies Orchid Lounge across the alley. Before the Second

World War, the hubs of the business had been Chicago, Cincinnati, Dallas, and Los Angeles, but within a few years the country

music business centered itself in Nashville.

Roy Acuff and Fred Rose had started Acuff-Rose Publications in 1942, and its success inspired Jack Stapp to follow suit. The

fact that Stapp went into partnership with a New Yorker shows the fast-growing impact of country music. Country songs like

Pee Wee King’s “Tennessee Waltz” and Hank Williams’s “Cold, Cold Heart” (both published by Acuff-Rose) became hits for pop

singers and gave others the idea that there was money in country music.

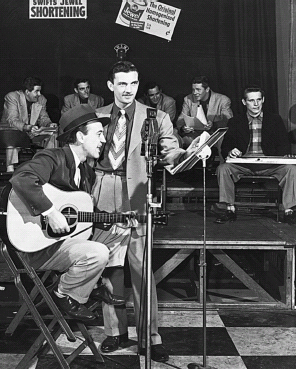

The Louvin Brothers with their producer, Ken Nelson.

JACK STAPP:

Lou Cowan was my superior during the war in England. We were involved in propaganda broadcasting to Europe. He’d made a reputation

in radio with shows like

Stop the Music, Break the Bank,

and so on. We stayed in touch, and one day he called me from Chicago. “Jack, you’re starting to make some noise down there

with that country music.” He had an idea for a country music show and he came down. After the audition we went across the

street for a sandwich, and that’s where the idea for Tree Music was born. Lou suggested it, thinking that with my contacts

at the Opry and the station I’d be able to get a lot of songs recorded.

Tree Music started in 1951, and Stapp’s songwriters would eventually include Roger Miller and Willie Nelson. Jim Denny launched

Cedar-wood Music in 1953, and his company went on to sign Mel Tillis, John D. Loudermilk, and many others. But Acuff-Rose,

which had been established almost ten years earlier, remained the major player in Nashville’s music publishing scene with

Hank Williams, Pee Wee King, Don Gibson, Marty Robbins, and later Roy Orbison and the Everly Brothers.

A few recording sessions had been held in Nashville in the 1920s, but Eddy Arnold’s first-ever recording session at the WSM

studios in December 1944 is generally reckoned to mark the birth of the recording business in Nashville. Almost three years

later, several WSM engineers launched the first professional studio in Nashville. They located it near WSM in the Tulane Hotel,

and named it the Castle Recording Laboratory because WSM was known as the Air Castle of the South. When Ernest Tubb and Red

Foley recorded at Castle in August 1947, the recording business in Nashville was underway. Tubb and Foley recorded for Decca

Records, and Decca’s Paul Cohen relied heavily on WSM’s musicians, especially pianist Owen Bradley, to arrange the sessions.

Bradley would later take over from Cohen and sign Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn, and many others to Decca.

The music industry in Nashville grew so quickly in the years after the Second World War that WSM announcer David Cobb coined

the phrase “Music City U.S.A.”

DAVID COBB:

I wish I could remember the exact date, but I’m sure it was circa 1950 because we celebrated Red Foley’s fortieth birthday

that same year. We originated some sustaining (that is, noncommercial) programs for the NBC network. One of them was

The Red Foley Show,

and I was the announcer. One morning, I felt that my opening words would require something that placed a little more emphasis

on Nashville, so one morning it came out. “From Music City U.S.A., Nashville, Tennessee, WSM presents

The Red Foley Show.”

It fell trippingly from the tongue and felt right, like a good billboard should. Right after the show I got word that Jack

Stapp wanted to see me in his office. When I walked in, he was beaming. “Where did you ever get an idea like Music City U.S.A.?”

He thought it was the greatest thing since George Hay had named the Grand Ole Opry. From that day, whenever Jack Stapp wanted

a catchy phrase, he would come to me for it, but I was never able to equal “Music City U.S.A.”

The Red Foley Show,

where David Cobb (standing at mic) coined the name that stuck, Music City U.S.A.

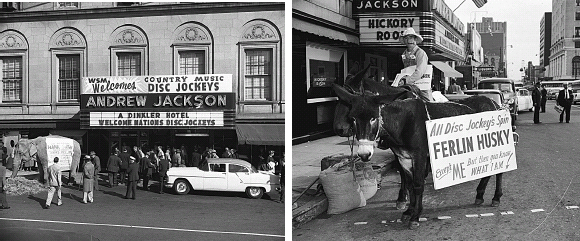

In 1951, Harianne Moore in WSM’s advertising department suggested bringing all of the disc jockeys around the country who

spun records by Opry stars to Nashville for a celebration. Fewer than fifty came, but the event was enough of a success for

it to become the annual Disc Jockey Convention, which itself metamorphosed into Country Music Week. It was a chance for the

artists to thank the disc jockeys and for the disc jockeys to tape spots with the artists that could be played on their local

stations.

Although the Grand Ole Opry represented the pinnacle of the country music business, the cast was rarely stable for long. Several

artists from the show’s earliest days, including Sam and Kirk McGee and Uncle Dave Macon, were still there; in fact, as Uncle

Dave grew older, he worked fewer road dates and became the Opry mainstay he always said he’d been. He celebrated his eightieth

birthday at the Opry, and passed away eighteen months later on March 22, 1952.

WSM press release:

Uncle Dave Macon, known to millions of radio listeners as “Dixie Dewdrop” of WSM’s Grand Ole Opry, died at Rutherford Hospital

after an illness of several weeks. He was 81 years old last October 7. He was one of the small group of entertainers who,

a quarter of a century ago, joined George Hay in the Grand Ole Opry, creating a new interest in folk and hillbilly music which

today has grown nationwide, making Nashville known as the folk music capital of the country. His last appearance on the Grand

Ole Opry was on Saturday March 1. He traveled with Opry road troupes until 1950.