The Grand Ole Opry

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

Copyright © 2006 by The Grand Ole Opry

®

, Gaylord Entertainment

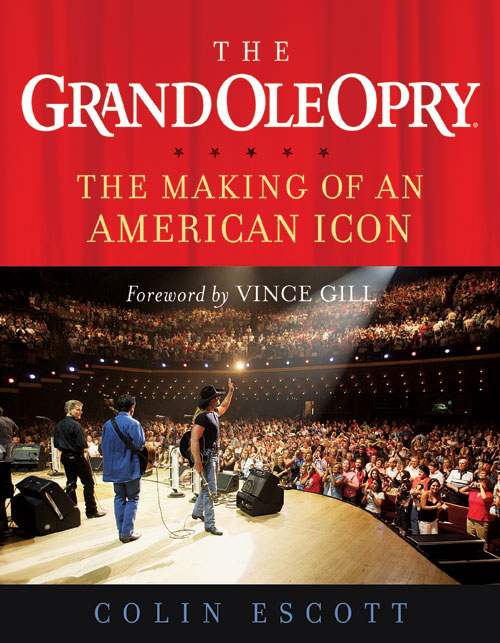

Front Cover photo: Grand Ole Opry member Trace Adkins receives a standing from the Opry audience, 2005. Copyright Grand Ole

Opry

®

. Photo by Chris Hollo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

Center Street is a division of Hachette Book Group.

The Center Street name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group.

First eBook Edition: November 2006

ISBN: 978-1-599-95248-2

CONTENTS

3: “G

REATEST

S

HOW ON

E

ARTH FOR THE

M

ONEY

”—T

HE

O

PRY

H

ITS THE

R

OAD

10: “A F

RIEND OF A

F

RIEND OF

M

INE IS A

F

RIEND OF

O

TT

D

EVINE

”

11: “A

LL

M

Y

H

IPPIE

F

ANS

”—T

HE

B

LUEGRASS

R

EVIVAL

14: W

HO

’S G

ONNA

F

ILL

T

HEIR

S

HOES

?

A NOTE FROM THE GRAND OLE OPRY

The Grand Ole Opry has always had that special something that separates it from every other form of American entertainment:

its people.

This book is dedicated to the dreamers who, for going on a century, have made their way to the Opry stage, aspiring to lend

their voices to the Opry’s song. Country music’s home has been built upon their dreams, their performances, and their undying

commitment.

This book is dedicated as well to those in the pews, cars, and living rooms around the world who have dropped by or tuned

in over that same course of time, sharing in the Opry dream while laughing and clapping along.

Indeed, the Opry is set apart by its people. Good people.

FOREWORD

by Vince Gill

People call the Grand Ole Opry a “family show,” and that’s exactly what it is. A lot of my deep appreciation and reverence

for the Opry is attributable to my parents, and the generation of my family that came before me. My mom was born the year

the Opry started, 1925. My dad taught me how to play guitar and my mom played the harmonica, and my grandmother played the

piano in church. That was the generation that sat around the radio on Saturday night listening to the Grand Ole Opry. Even

though that era was disappearing by the time I was born, all the records I heard were by Opry stars. Jim Reeves, Patsy Cline,

Chet Atkins, and so on. Respect for the Opry and all it stood for was bred in me.

Thankfully, I got to know several of the performers who carried the show from the 1930s and’40s until quite recently: Minnie

Pearl, Roy Acuff, Grandpa Jones, Bill Monroe, Jimmy Dickens, and Hank Snow. Every opportunity I got to sing with stars like

Roy Acuff was a moment of pride for me because those were the heroes of my parents and my family. There’s something so much

deeper in my connection with those artists than the fact that we’re all singers. I feel that I’m respected by the generation

of Opry performers that came before me because I have reverence for them, and I back it up by being at the Opry every chance

I can.

When you bring as many artists onto a stage every Saturday night as the Opry does, it’ll never be right for everybody all

the time. I hear people saying that the show isn’t what it used to be, but you’ve got to take the long view. History alters

what we think of as country music, and that’s why the Grand Ole Opry is so important, because it’s every era of country music

together on one stage. You can even make a case for saying that “country music” as we know it didn’t come along for maybe

twenty years after the Opry was born. Before that, it was string bands, and those of us who love string band music and have

some of that in our style—Alison Krauss, Ricky Skaggs, Marty Stuart, myself—owe the Opry a debt of gratitude for keeping that

music alive through some pretty lean years.

In these pages you’ll find the story of the Grand Ole Opry in the words of those who were there. As you’ll see, it wasn’t

always smooth sailing, but if the Opry had always been perfect and well-oiled, I don’t think it would have lasted. The turmoil

and struggles made people fight to keep it alive and keep it vibrant, and those struggles are the way in which every generation

redefines what the Opry is.

There are so many lessons that every artist can learn from the Grand Ole Opry. I started out as a picker, and I already knew

the backup musicians there, and I saw at once that it wasn’t all about the stars. That’s why you treat everyone the same.

Artists, musicians, backstage people. It takes a village, and the Opry taught me that.

The Opry also helped me understand the difference between what’s really important and what’s trivial when it comes to making

music. These days, our culture has become disposable. What’s the hip, cool, and groovy thing right now? The engaging thing

about the Opry is that it doesn’t buy into that theory, and I don’t think it ever will. You can go out there and see fifty

years of what’s truly important in country music history. What our music has been and what it is today. That’s a great way

to spend an evening. Then there’s the unpredictability of the Opry. Jazz singer Diana Krall came out and sang with me, and

no one expected it. Some nights there’ll be giant train wrecks. Someone will say, “Hey, come out and do a number with me,”

and it just won’t work, but then you’ll get those moments that only happen at the Grand Ole Opry... and there have been so

many. One night I remember in particular came toward the end of Roy Acuff’s life. He couldn’t see too well, so he’d get right

up np1 to you while you were performing. He loved my song “When I Call Your Name,” and asked me to sing that, and he had a

big tear running down his cheek. I still choke up thinking about it.

It hurts me to see country artists who think they don’t need the Grand Ole Opry. On one level, I get it. Things are different

today than they were sixty years ago. But the Opry can and will stay relevant because enough people have reverence for it

and care about its future as much as its past. I had an afternoon with Roy Acuff many years ago and he shared things with

me that I’ll probably never tell anybody, but he said, “I was a real big star back in the forties. Hollywood was after me,

but the Opry

needed

me.” That stuck with me. I thought, “That’s what it takes sometimes. Somebody willing to set aside their best interests,

and do something for the good of the cause.” When I do the Opry, they give me Mr. Acuff’s dressing room. I think it’s because

I always leave the door open.

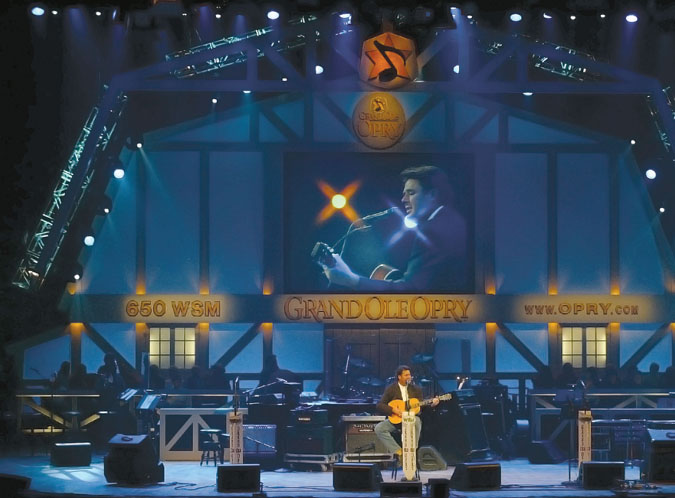

Vince Gill at the Grand Ole Opry.

For the Grand Ole Opry’s eightieth anniversary, we took it back to Carnegie Hall. The Opry had been there twice before, in

1947 and 1961, and people asked us how it felt to stage the Opry there. I’ve always found that people respond to great music

wherever they are, but I was so proud to see our music in that venue. Carnegie Hall has an amazing weight to it. Even the

few country LPs recorded at Carnegie Hall are landmark recordings. When you think how derided and looked down upon this music

was at the time the Opry was born, it makes you realize how far we’ve come, and it makes you realize the Opry’s role in getting

us there.

Even today, the Grand Ole Opry is the first thing people think about when they think of country music. It conjures up the

history of our music. In this book, you’ll hear the words of those who went before us, and the words of those who make the

Opry what it is today. When you step onto the Opry stage or sit in the audience, you feel the presence of those who went before

and created the music that we’re carrying on. I embrace the ghosts. If they’re hanging out in the rafters, they’re most welcome.

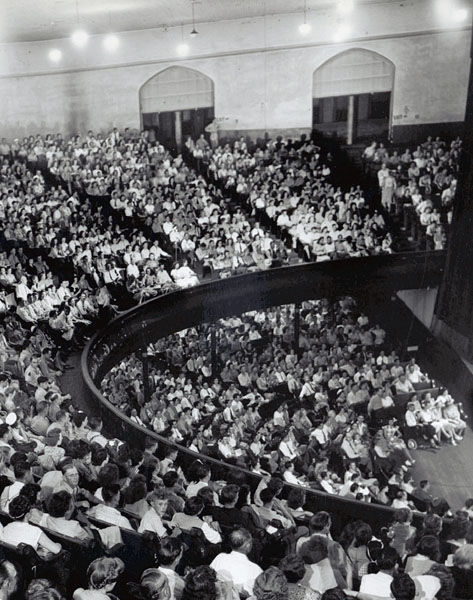

There wasn’t an empty seat at the Grand Ole Opry’s eightieth birthday celebration in October 2005. Among the cast members

onstage that night, there was one—Little Jimmy Dickens—who’d first appeared on the show in 1948. Back then, he’d mingled with

veterans of the show’s earliest days. At the eightieth, he stood backstage with Opry stars from the last fifty years. In the

half-light, they formed a ragged, unbroken circle.

Today’s Opry members coexist happily with the ghosts. No one who plays bluegrass can forget that Bill Monroe introduced the

music from the Opry stage. Today’s Opry members know that the torch has been passed to them, and that they in turn must pass

it on. Away from the Opry, today’s top stars can play to stadiums full of fans; at the Opry, they play to four thousand people,

some of whom have little idea who they are. They have just a few minutes to win over the crowd while artists from the last

fifty years watch from the wings. That’s what makes the Grand Ole Opry one of the premier stages in American music.

Through the years, the legends of the Grand Ole Opry have become known by one name. Cash, Acuff, Hank, Patsy, and so on. At

the eightieth anniversary, Garth was there. He emerged from a brief self-imposed retirement, and, in case he, or anyone else,

was wondering, he’s still the most powerfully iconic presence in country music. Before joining Steve Wariner for some duets,

he went onstage as the fourth member of a quartet alongside Little Jimmy Dickens, Porter Wagoner, and Bill An-derson. Backstage,

every hand was shaken and every photo taken. Old-timers used to call it “shake and howdy,” and it’s a tradition that has almost

disappeared. Garth, though, seemed genuinely pleased to carry it on. Ernest Tubb, who personified shake and howdy, would have

smiled his big benevolent smile and approved.