The Grand Ole Opry (3 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

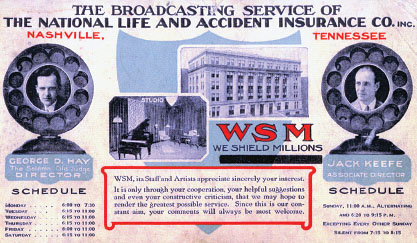

WSM went on-air at 7:00 p.m. on October 5, 1925. It began with an announcement by Edwin Craig, followed by a prayer from Dr.

George Stoves, pastor of the West End Methodist Church. The Shrine Band played the national anthem, and there was a dedication

program that lasted until two o’clock in the morning. Craig didn’t launch WSM with the idea of programming “folk” or country

music (in fact, country music and blues were the only types of music unrepresented in the inaugural gala), but he hired a

program director who’d already stumbled on the idea for the radio barn dance.

JACK D

E

WITT:

Edwin Craig and the people at National Life were first-class people, and they really understood the community. They wanted

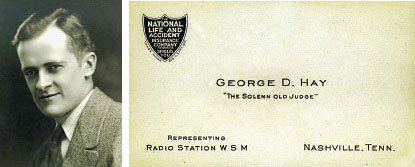

a radio station that reflected the community. That’s why they brought in George Hay as station manager, and that was the middle

of November 1925.

JUDGE HAY’S DAUGHTER, MARGARET:

George Hay was a Hoosier, born in Attica, Indiana, in 1895, son of a jeweler. His mother was widowed when he was ten and for

the most part allowed him to grow up on his own, never managing to overcome her depression over the loss of her husband. Unable

to complete high school in Chicago, where they had moved, he turned to supporting himself by way of many jobs.... He was basically

democratic. A gentle man with impeccable manners.

George D. Hay: “The Opry is built to entertain that eighty-five percent of our population sometimes vulgarly referred to as

‘the masses.’ The whole idea behind it is one of friendliness and not of smartness.”

GRANT TURNER, Opry announcer:

He told me that he wrote a column for the Commercial Appeal in Memphis called “Howdy, Judge.” He’d write about all the people

who’d been arrested over the weekend. Then the Commercial Appeal decided to build a radio station, and they told him, “You’re

the only one on staff who might be able to adapt himself to running this station.” Judge knew nothing about radio, but he

took it on.

JUDGE HAY:

I was on from eight’til nine o’clock every night. Just plain everyday talk, all ad-lib. Direct and simple and full of human

interest. At first I signed off with my initials, then one day, on the spur of the moment, I decided to sign off with my childhood

nickname. From that day, I closed every broadcast with “This is your Solemn Ol’ Judge, George D. Hay.”... I got the nickname

“Judge” as a child. I was such a solemn kid, relatives would say, “He’s solemn as a judge.”

The

Commercial Appeal

sent [me] to the Ozarks to cover the funeral of one of America’s World War I heroes. We rode behind a mule team thirty miles

up in the mountains from Mammoth Spring, leaving very early in the morning. The neighbors came from miles around in respect

to the memory of this United States Marine, who gave his life to preserve their way of life. The young man’s father welcomed

them as he stood on the crude platform in the country churchyard, but closed his brief remarks in this manner: “Let all those

who were against the government during the war pass on down the road.” We didn’t see anyone leave.

We lumbered back to Mammoth Spring and filed our story, and spent a day there. In the afternoon, we sauntered around town,

at the edge of which there lived a truck farmer in an old railroad car. He had seven or eight children, and his wife seemed

very tired with the tremendous job of caring for them. We chatted for a few minutes and the man went to his place of abode

and brought forth a fiddle and bow. He invited me to attend a hoedown the neighbors were going to put on that night until

the crack of dawn in a log cabin about a mile up a muddy road. He and two other old-time musicians furnished the earthy rhythm.

About twenty people came. There was a coal oil lamp in one corner of the cabin and another in the “kitty” corner. No one in

the world has ever had more fun than those Ozark mountaineers did that night. It stuck with me until the idea became the Grand

Ole Opry.

I never would have left the South if a Chicago station, WLS, had not offered so much more money. They asked me my price and

I said, “Seventy-five dollars a week.” It was so much more than I’d ever made in Memphis. That was 1924. Several weeks after

the WSM launch, I was in Dallas, and [WSM treasurer] Mr. Runcie Clements and Mr. Craig asked me to come to their new station.

Within a few weeks after it started, I came to WSM as director.

Edwin Craig’s old-money background didn’t prevent him from enjoying country music, and he shared Judge Hay’s enthusiasm for

preserving the old ballads. As a student at Branham-Hughes Military Academy in Spring Hill, Tennessee, Craig had played mandolin

in a string band, together with several classmates and, he said later, “a young Negro boy who was the janitor in our dorm.”

JUDGE HAY:

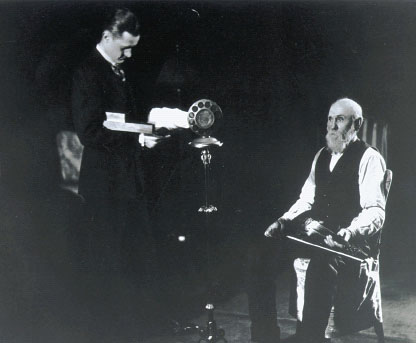

The Grand Ole Opry is a very simple program, [and] it started in a very simple way. WSM discovered something very fundamental

when it tapped the vein of American folk music, which lay smoldering in small flames for about three hundred years. Realizing

the wealth of folk music material and performers in the Tennessee Hills, [I] welcomed the appearance of Uncle Jimmy Thompson,

who went on the air at eight o’clock Saturday night, November 28, 1925. Uncle Jimmy told us that he had a thousand tunes.

He was given a comfortable chair in front of an old carbon microphone, while his niece, Miss Eva Thompson, played his piano

accompaniment.

Uncle Jimmy was about eighty years of age. He told us that he had recently come out with a blue ribbon in a big fiddlers’

contest and shindig in Dallas, which had lasted about a week. WSM’s studio was rather small and beautifully decorated in a

quiet way with red drapes, suggesting a very dignified type of music. Uncle Jimmy was somewhat amazed, but by no means rattled

or thrown for a loss. He was the p1rovert type and nothing about the radio seemed to bother him, not even the fact that it

was a new proposition. After he had played for about an hour, we suggested very softly on account of the microphone that perhaps

he had played enough. His reply came back not so softly: “Why shucks, a man don’t get warmed up in an hour.”

George D. Hay introduces Uncle Jimmy Thompson.

Uncle Jimmy was cantankerous and hard-drinking, and although he wasn’t quite as old as Hay thought (seventy-seven, not eighty),

he’d begun fiddling before the Civil War. He claimed that his fiddle, “Old Betsy,” had come with his ancestors from Scotland.

Despite his advanced years, he immediately saw the potential of radio. “I want to throw my music out all over the Americee,”

he told his niece. Seated in front of WSM’s microphone, he’d yell out, “Tell the neighbors to send in their requests, and

I’ll play’em if it takes me all night.” Like Judge Hay, Uncle Jimmy believed his music needed no more sophistication than

it already had.

JACK D

E

WITT:

A guard at the National Life building said, “Hey, Uncle Jimmy, [classical violinist] Fritz Kreisler is in town. Would you

like to hear him perform?” They gave him a ticket, and Uncle Jimmy went down to where Fritz Kreisler was performing. Anyway,

Uncle Jimmy stayed down there about thirty or forty minutes, and the guard said, “How’d you like Fritz Kreisler?” Uncle Jimmy

said, “Aw, he just kept practicin’ and practicin’. He never did strike up a tune, so I left.”

But as Hay’s new barn-dance show became popular, Uncle Jimmy became more of a liability than an asset, and by 1928, he’d almost

stopped appearing.

SAM KIRKPATRICK,

Uncle Jimmy’s neighbor:

I’ll never forget the last night Uncle Jimmy played. He kinda liked his bottle pretty well. He was playin’, and before he

finished, there was this stopping, and we didn’t hear nothin’ for a minute. Then George Hay come on, and said Uncle Jimmy

was sick tonight. Come to find out he’d just keeled over and passed out.

The unpolished performers led to unrelenting criticism of Hay’s Barn Dance, and the fact that it stayed on the air infuriated

Craig’s country club friends. WSM, they argued, should enhance Nashville’s reputation as the “Athens of the South,” a place

of commerce, culture, and learning. If anything, WSM should try to educate the “hillbillies,” not pander to them. Craig, though,

stood his ground.

JUDGE HAY:

Edwin Craig saved the Opry. He’s the man who kept me from being run out of town and the Opry with me during those early days

when we didn’t know from week to week whether this community would let the Opry live. Every Monday morning brought a crisis.

Conservative elements of Nashville’s population railed against hillbilly music taking such a prominent place in the programming

of this new station. Every week, I’d take my troubles to Mr. Edwin Craig, and he handled them in some way unknown to me. All

I know is that the Barn Dance, as it was called then, stayed on the air.

Almost as soon as it went on the air, WSM’s Barn Dance attracted performers from in and around Nashville. They weren’t paid,

but didn’t care because music was a pastime, not a profession. One of the show’s early mainstays was a genial country physician

from Sumner County, Tennessee, Dr. Humphrey Bate.

Dr. Humphrey Bate (left) led his band on WSM before the Opry started and was on one of Nashville’s first stations, WDAD, before

that.

Just a dozen or so long-unavailable recordings are the only tangible reminders of Dr. Bate, but his importance to the Opry

in its early days was inestimable. He traveled widely and had a good ear. If he heard someone he liked, he’d recommend them

to Judge Hay. Bate himself played the harmonica, and, as soon as he heard DeFord Bailey, he knew he’d found one of the instrument’s

finest practitioners.

D

E

FORD BAILEY:

Dr. Bate wouldn’t take no for an answer. They had a hard time getting me to go down there. I was ashamed of my little cheap

harp and them with all them fine, expensive guitars, fiddles, and banjos. But Dr. Bate told me, “We’re going to take you with

us if we have to tote you.” He told the Judge, “I will stake my reputation on the ability of this boy.” The Judge knew at

once he wanted me. He give me twodollars and told me to come back np1 week.