The Grand Ole Opry (7 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

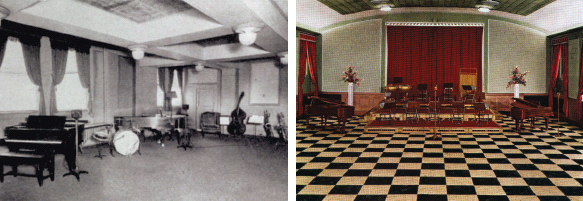

left: WSM’s Studio B. The instruments show that WSM was programming pop music in addition to country.

right: WSM’s Studio C. The attractively decorated studio prompted Armstrong Flooring to feature this colorized photograph

in an ad campaign. Jack DeWitt: “[Studio C] was a big conference room. They put chairs in it for the Opry, but the National

Life officials didn’t like that at all.”

An even larger, auditorium-style space, Studio C was completed in Feb- ruary 1934, and could seat about five hundred audience

members. Buteven that larger capacity wasn’t enough to accommodate the Opry crowds.

JUDGE HAY:

The crowds stormed the wrought-iron doors of the home office building to such an p1ent that our own officials could not get

into their offices when they felt it necessary to do so on Saturday nights. The payoff came one Saturday night when our two

top officials were refused admission to their own offices. Ouraudience was very politely invited to leave the building, and

for some time we did not know if the Grand Ole Opry would be taken off the air. We broadcast for some time without any audience,

but something was lacking. It seemed that a visible audience was part of our shindig.

But that wasn’t quite the way WSM’s news service reported it.

WSM

press release, October 21, 1934:

The Grand Ole Opry has outgrown its old clothes. Last February [1934] when the new WSM auditorium-studio was completed, WSM

officials felt they had solved the problem of accommodating the crowds which assemble every Saturday night. From February

to July, the audience was admitted to the Opry in the new auditorium-studio, which has a capacity of 500. Three color tickets

were issued, each admitting a person to one hour of the Opry. Thus 1,500 were taken care of on Saturday night. After a summer

of no audiences, the Opry again opened its doors and this time even the large auditorium studio of WSM proved inadequate.

The Opry cast on the stage of the Hillsboro Theater, 1935.

GRANT TURNER:

Scouts were sent out to find an auditorium that would accommodate a few hundred to one thousand people. The struggling Nashville

community playhouse at Hillsboro and Belcourt rented out their quarters [October 3, 1934]. A makeshift control room was constructed

in one corner of the stage. The bands could never keep to the time slots. They would perform a song, and all of a sudden,

before the Judge could thank them and get them off, they’d burst into another song. Judge told Harry Stone of his trouble,

so Harry suggested that they get a musical contractor to come assist the Judge and put some muscle into the show. Vito Pellettieri

was that man.

VITO PELLETTIERI,

Opry stage manager:

I don’t think there will ever be a man who could go in front of a microphone like Mr. Hay. Never, never will be another one.

I went to see Mr. Hay, and he laughed. “What are you doing out here?” I said, “I want to help you on the Opry tonight.” He

said, “What are you going to do?” I said, “Your guess is as good as mine.”

I’d told Harry Stone I didn’t know a thing about those damn hillbillies. That first night, I saw all these open, horse-drawn

wagons. The beds were filled with hay to make it easier on the backside. There were only a few cars and most of them were

Fords. The acts were string bands. Fiddles, banjos, and basses. They would come in off the road and half of them were full

of mountain dew. They’d show up when they felt like it. I’d take four numbers from them, which would be about ten minutes,

then I would pass it over to Mr. Hay, and he’d announce the numbers, and we tried to keep it up until twelve midnight.

It wasn’t unknown for Vito Pellettieri to phone a top Opry entertainer and say, “Hey, you no-good hillbilly. What kind of

garbage are you going to dish up this week?”

I got out of there. I went home, took me a big drink, and told my wife there weren’t enough devils in hell to ever drag me

back. She says, “You stay with it. That’s your job. You stay with it.” So I went to Harry, and I says, “Harry, I can’t do

it the way you’ve got it. I want to block that show off in fifteen-minute blocks. I want to tell each one of the fellows when

they’re supposed to be here, and if they’re not here... that’s it.” Np1 Saturday night, why, I blocked them off in fifteen-minute

blocks and put them on. I told each one of them, “Np1 Saturday night, you’re on at a certain time.”

JEANNIE SEELY,

Opry star:

Vito was a wonderful dirty old man. He loved it when I said suggestive things to him. But he was full of good advice. Little

things, like he told me, “Never turn your back on the audience, even if you’re taking a bow.” He taught us all like that.

Until Vito Pellettieri came into the picture, the Opry’s only advertiser (or sponsor) was National Life, but after Vito divided

the show into segments, he came up with another idea.

VITO PELLETTIERI:

After I guess maybe three or four months, I told Harry, “Now, it’s all right, but I’m very commercial. Why can’t we sell this

stuff?” He said, “Well, if you feel we can do it, why, we’ll just sell it.” So he sold fifteen minutes, then thirty minutes

to the Crazy Water Crystals. So I got a format up. The fact of the matter is that the show that’s on the Opry right now is

the same format I gave’em.

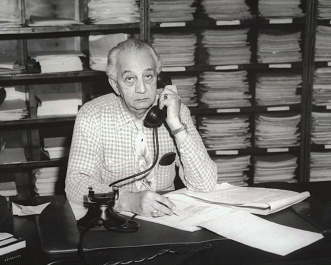

Vito Pellettieri with the La Dells. Bill Anderson, Opry star: “He was the dirty-talkingest, filthy-mouthed old man I ever

was around in my life, and I say that with more love and respect than you could ever imagine.”

Crazy Water Crystals was a Texas company that claimed its product could cure an unlikely number of ailments. Analysis revealed

that the crystals were mostly horse salt and laxative, and the Federal Communications Commission eventually closed the airwaves

to them, but by then Vito Pellettieri had established the Opry’s “sponsored segment” format. In the late 1930s, thirty-minute

segments could be had for $350. And Pellettieri, the son of Italian immigrants and a former “sweet” band leader, came to appreciate

both the Opry and its performers.

VITO PELLETTIERI

When I was in the bands, somebody would get sick or be in financial trouble. I’d go around to the other musicians and they’d

say, “Hell, no, I work as hard for my money as he does for his. He didn’t have to go out and blow it all’til he was broke.”

But then I got with the hillbillies. One of them would get sick and you’d go tell the others, and they’d say, “Damn, is that

right?” And they’d haul out their fifties and hundreds. I never saw any of them back away from one of their own people in

trouble. When I saw that, I said to myself, “Well, from now on, I’m going to be a hillbilly.”

Vito Pellettieri and his saxophone orchestra . . . in business until the Depression.

With Harry Stone in the front office, Vito Pellettieri backstage, and Judge Hay auditioning the artists and emceeing the show,

the Grand Ole Opry was poised to become radio’s leading barn dance.

“GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH FOR THE MONEY”—THE OPRY HITS THE ROAD

T

he grand Ole Opry’s home turf, the South and Southeast, was especially hard hit by the Depression. As personal incomes fell,

the country music record business almost disappeared, and records by top artists sold as few as five hundred copies. Offering

free entertainment, the Opry prospered, but faced stiffer competition as an increasing number of stations devoted airtime

to hillbilly music. Meanwhile, the music itself was changing. The first nationwide country star, Jimmie Rodgers, died in 1933

without once playing the Opry, and his success made it clear that Judge Hay’s concept of amateur string bands was out-of-date.

The Opry needed stars, but stars wanted to make a living from their music. With that in mind, Hay organized the Artists Service

Bureau to book and coordinate shows around the mid-South.

Grand Ole Opry tent show, “The Greatest Show on Earth for the Money.”

PEE WEE KING,

Opry star: