The Grand Ole Opry (11 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

Despite their success as a team, the split between Bill and his brother Charlie was far from amicable.

Bill Monroe.

MINNIE PEARL:

They say that if Bill had to travel east to get a booking, he would go out of his way to go by his brother’s house in Kentucky

and get him out of bed in the middle of the night just so they could have a fight.

CHARLIE MONROE:

He won’t last on the Opry. Wait’til people find out how difficult he is to get along with.

The Monroe Brothers had been a partnership in which Bill was the junior partner, but he never again took a backseat. His opinions

on how his Blue Grass Boys should look and play were unbending. He dressed soberly and required that his band members did

likewise. Unlike other country acts at that time, they did little or no comedy and barely moved onstage

BILL MONROE:

After Charlie and me broke up, I was searching for a name for my group, and I wanted a name from the state of Kentucky. Before

I come to WSM, I’d already decided on using the name “bluegrass,” because that’s what they’d call Kentucky, the Bluegrass

State, so I just used Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys. I showed up at WSM on a Monday morning, and I met the Solemn Ol’

Judge. David Stone and Harry Stone was there. They was all goin’ out to get some coffee and something to eat. They told me

that Wednesday was the audition day. So they come back and I sang “Mule Skinner Blues,” “Bile Them Cabbage Down,” numbers

like that, and a gospel song.

CLEO DAVIS, Bill Monroe’s guitarist:

They put us in one of the studios, and we really put on the dog. We started out with “Foggy Mountain Top,” then Bill and I

did a duet with duet yodel, fast as white lightning. We came back with “Fire on the Mountain” and “Mule Skinner Blues.” That

sewed it up.

BILL MONROE:

They said I could go to work for’em that Saturday, or I could go on lookin’ for another job. Maybe I could make more money.

I told’em I wanted to be at the Grand Ole Opry. They said, “Well, you’re here, and if you ever leave, you’ll have to fire

yourself.”

One of the earliest incarnations of the Blue Grass Boys, around late 1939 or early 1940. From left: Art Wooten, Bill Monroe,

Cleo Davis, and Amos Garren.

Bill Monroe was the only Opry performer not to admit to nerves on the first night.

BILL MONROE:

I wasn’t a bit nervous that first night because I knew I could do what I was up there to do. I sung “Mule Skinner Blues,”

and it got three encores. The management just stood and looked at us. They knew the music was altogether different. They didn’t

know me, but they knew I had a music that would fit in at the Grand Ole Opry. It would be fine for the farm people, the country

people. It had a hard drive to it. Back then, they just drug the music out. Our music was pitched up at least two or three

changes higher than anyone had ever sung it at the Opry.

CLEO DAVIS:

Performers such as Roy Acuff, Pee Wee King, and Uncle Dave Macon who were standing in the wings could not believe when we

took off so fast and furious. Those people couldn’t even think as fast as we played. There was nobody living who had ever

played with the speed we had.

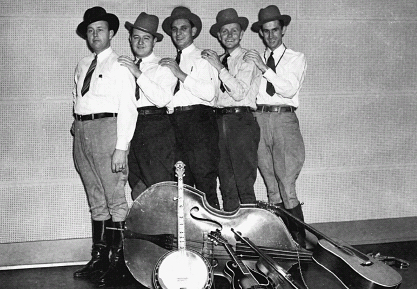

From left: Bill Monroe, Howdy Forrester, Clyde Moody, Cousin Wilbur (Wesbrooks), David “Stringbean” Akeman. Cousin Wilbur:

“Sometimes we’d go to bed one night a week, and it was a good thing we didn’t go to bed more often, because if we had, we

wouldn’t have had no money to pay the bill.”

One of the very few surviving photos of the classic lineup of the Blue Grass Boys. Onstage at the Opry for Purina, from left:

Lonzo Sullivan of Lonzo and Oscar clowning to the side; Chubby Wise, Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, and Earl Scruggs.

BILL MONROE:

I dress the way a lot of Kentuckians used to dress years ago. I think it was a help to the music to dress as we did. I never

would have dressed up like the other bands. I wanted to let people know that my music was up where I wanted it. It wasn’t

no low, down-to-earth music. I want people to listen to it. I want people to know I’m playing it for them, right from my heart

to theirs.

In 1945, Bill Monroe hired Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, and bluegrass music began to take shape on the Opry stage.

Bill Monroe: “The Opry goes out over WSM, and those are my initials, William Smith Monroe.”

Ricky Skaggs: “I think, on some

level, Bill really believed that the station needed a powerful good name, and they named it after him.”

BILL MONROE:

Back in the early days, Stringbean was the first banjo picker with me. I’d heard the banjo back in Kentucky, and I wanted

it in with the fiddle and the rest of the

,

instruments. Stringbean give us a touch of the banjo, but he quit. He went into

”

the service. When I heard Earl, I knew the banjo picking would fit my music. He could take lead breaks like the fiddle. Without

bluegrass, the banjo never would have amounted to anything. It was on its way out. Fiddlers would have been mighty scarce

without bluegrass, too

RICKY SKAGGS,

Opry star:

He was looking for a sound he could call his own, and with the addition of Flatt and Scruggs, his music had the drive that

he’d been looking for. It had taken a while, but he’d found his sound. It was old-time music on steroids. It was old, but

it was cutting edge. It would please the old-timers, but it appealed to a younger generation, too. The gospel quartet numbers

really solidified their following. They may not have lived the life they were singing about, but, man, could they sing about

it.

JAKE LAMBERT,

bluegrass musician:

Monroe’s band became one of the hottest groups working the Opry. Bill purchased a stretch automobile and they were on the

road almost seven days a week. When they finished a Friday night show they would head for Nashville and the Opry. Most of

the time they would leave as soon as the Opry was over and travel the rest of the night to do a Sunday matinee—maybe four

hundred miles away. Flatt said that there were many times [his wife] Gladys would bring his clothes to the Opry and he would

never go home. For both Lester and Earl, the road seemed to be endless. The personnel of the Blue Grass Boys in 1946 and’47

was Monroe, Flatt, Scruggs, Chubby Wise, and Howard Watts. This band would go down in bluegrass history as being probably

the best ever assembled.

After just two years, Flatt and Scruggs became disenchanted.

JAKE LAMBERT:

Flatt and Scruggs, as well as the rest of the boys, were making about sixty dollars a week, and that wasn’t bad money, except

for the long hours. Earl was the only one in the group with a high school education, and he took care of the money. He told

me that on many Saturdays, when the Blue Grass Boys rolled into Nashville for the Grand Ole Opry, he would be carrying between

five to seven thousand dollars. So both Flatt and Scruggs could see where the money was. They knew it would never be as sidemen.

In 1948, Flatt and Scruggs left to form their own band, but Bill Monroe recruited literally hundreds more Blue Grass Boys.

Many, like Flatt and Scruggs, would eventually lead their own bands, and some would attempt to take bluegrass in new directions,

but Bill Monroe’s vision of his music was unbending, and he would always remain caustic and dismissive of those who deviated

from it.

BILL ANDERSON,

Opry star:

The thing about Bill Monroe and his music is that he was very creative and flexible to a point, and then he became very rigid.

I watched him one time in the dressing room. He was working on a new song, an instrumental. The Blue Grass Boys were feeling

their way through it, improvising and changing it, but once they got it to where he liked it, he didn’t want it changed at

all. He let his guys be flexible until they got it to where he wanted it, then he set it in concrete.

Opry stars had told jokes... plenty of them, but there had been few comedians on the show until Sarah Ophelia Colley brought

her alter ego, Minnie Pearl, to the Opry stage. Born into a prosperous middle-class family, Sarah Colley aspired to be a professional

actor until she developed her Minnie Pearl character on the rural theater circuit. In the fall of 1940, she appeared as Minnie

Pearl at a bankers’ convention in her hometown, Centerville, Tennessee.

MINNIE PEARL:

I got a call from Harry Stone. He said that Bob Turner, a Nashville banker who was a friend of my father’s, had seen me do

a country girl character at a convention. “He says, you ought to be on the Opry. Would you like to audition for us?” I won’t

pretend that I always wanted to be on the Opry. I’d never thought about it one way or another, except I didn’t particularly

like the music. I auditioned in my street clothes. I still wanted to be Ophelia Colley, dramatic actress, doing a comedy part.

I wasn’t yet ready to be Minnie Pearl. The first night I was so scared. Judge Hay gave me the very best advice any performer

can get. “Just love them, honey, and they’ll love you right back.”