The Grand Ole Opry (14 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

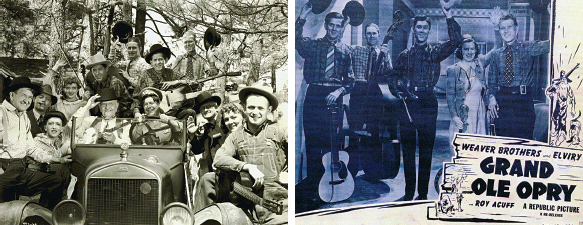

Stills and a lobby card from Republic Pictures’

Grand Ole Opry

movie, directed by former railroad worker Frank McDonald. Critic Evelyn Keyes said, “I’ve never seen anyone as terrified of

directing as Frank McDonald.” Regardless, he directed over a hundred movies, mostly low-budget westerns.

The Opry also attracted the attention of Republic Pictures, and in 1940 several Opry members were in a Republic feature,

Grand Ole Opry.

To secure Republic’s commitment, Judge Hay brought the producer to Uncle Dave Macon’s house near Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

JUDGE HAY:

After dinner, Uncle Dave invited us to be seated under a large tree in his front yard, where we discussed the possibility

of a Grand Ole Opry picture. As the producer and [I] drove back to Nashville, that experienced executive said, “I have never

met a more natural man in my life. He prays at the right time. He cusses at the right time, and his jokes are as cute as the

dickens.”

Knoxville News Sentinel,

1940:

The other night, Acuff and the other Opry players were a bit spryer with their songs and wits than usual. The Hollywood scouts

were in the audience. Republic Pictures had a producer, director, and writer there listening. “Roy and the others will start

packing soon for California,” said Jack Harris, WSM publicity director.

“Cameras are to start grinding on May 1.” The WSM man said that the picture was originally scheduled with Gene Autry, but

that didn’t go through.

The movie was short (just over one hour), and the plot was flimsy and didn’t have much to do with the Opry, but it was significant

that the movie colony in Hollywood thought that

Grand Ole Opry

was a salesworthy title for a nationally released picture.

JUDGE HAY:

We got the contract to do a Republic picture. Uncle Dave Macon was in it, and he always said that he couldn’t get along without

his country ham. Uncle Dave and I went out to Hollywood on the train. Roy Acuff had a station wagon and drove all the way

along the southern route with very few stops. Uncle Dave told Roy, “I’m not sure we’re gonna get enough to eat out there.

I’ve got three country hams. I want you to put them on top of your bus so we’ll be sure to have something to eat.” Uncle Dave

would go into restaurants out there and tell the cooks that he wanted a large order of eggs to go with his country ham so

he wouldn’t get too lonesome. Then he insisted that Roy carry the crates back to Tennessee so that he could use them for chicken

coops. When Uncle Dave visited the shore of the Pacific Ocean, he took out a tobacco sack and filled it with wet sand. That

was a token of his visit to the West Coast. We worked, I guess, two or three days on the picture. It had two hundred scenes

and each scene was a minute or less. Finally the director told us we could come over to a little shed and watch the rushes.

After a couple of minutes, Uncle Dave came on. His son Dorris was standing beside him in the movie plunking a guitar, looking

like a wooden Indian. Uncle Dave looked up there at the screen, stood straight up, and said, “Wheeeeeeeee, that’s me!” Hollywood

has seen many unusual people, none more so than Uncle Dave.

ROY ACUFF:

Hollywood, I came to find out it was phony. I’d say seventy-five percent of Hollywood is phony and maybe twenty-five is pure,

whereas I’d say that our business with the Grand Ole Opry is maybe ninety percent pure.

Movies weren’t the only other industry to benefit from the rapidly growing Opry business. When World War II ended in 1945,

there were still no recording studios or record companies in Nashville, but there was one pioneering music publisher.

VITO PELLETTIERI:

The two men who are responsible for Nashville being Music City are Roy Acuff and Fred Rose. Fred was on WSM and he’d written

songs for Gene Autry. I says, “Fred, I’m having trouble clearing tunes. I just wish we had a publisher here that can do it.

Nobody will take the hillbilly tunes. Nobody wants them, and I’ve got to have them.” He said, “Well, I can help you out if

you get Roy Acuff interested in this thing.” So I went to Roy and I told him what Fred had said. Roy said, “Yes, I’ll be interested.”

He asked me what kind of fellow Freddie was, and I told him the finest there was. And that was the beginning of Acuff-Rose,

the publishing company.

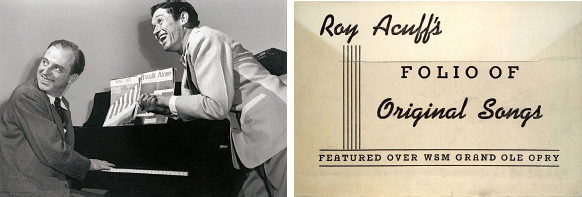

left: Fred Rose and Roy Acuff. Hank Williams: “Fred Rose came to Nashville to laugh, and he heard Roy Acuff and said, ‘By

God, he means it.’ ”

right: One of Roy Acuff’s first songbooks.

DAVID STONE:

Roy was selling songbooks. He had a little trailer home out on the east side, and he had girls come in daily and stuff them

in the mail. So he and Freddie got into the publishing business, and it blossomed from the first day. Roy advanced some money

to Fred. The money was put in five different banks, so Roy said nothing could happen to all five accounts at once.

ROY ACUFF:

We were like blind pigs searching for an acorn. I was selling a lot of songbooks and I had accumulated a little extra money.

I wanted to make some kind of investment, and I knew there wasn’t anyone publishing country music, at least not in a big way.

I talked to Harry Stone and Vito Pellettieri, who knew Fred real well and knew a lot about music. Finally, I went to Fred,

and he thought I was kidding. But it kind of got to him. I told him I had saved twenty-five thousand dollars and I took it

to the bank to put in his name. That’s how much I trusted him. That money didn’t come from personal appearances and it didn’t

come from playing the Grand Ole Opry. It came from selling songbooks because I knew my songs were hotter’n a pistol. I paid

eighty-five dollars for a spot on the Opry broadcast advertising a book of my songs with pictures, and by Wednesday there

were twenty-five thousand letters in the post office. People paid twenty-five cents apiece for them.

WESLEY ROSE,

Fred Rose’s son:

Nashville wasn’t a music town. But there was the Grand Ole Opry, and that was the reason we stayed. The fact that the Opry

was here made us decide to settle in Nashville permanently. The artists were available every weekend and we could take our

songs to them. Nowhere else in the world did artists congregate like that every weekend.

Despite the Opry’s ever-increasing crowds at home and on the road, it had yet to find a semipermanent base. The primitive

Dixie Tabernacle was already deemed unsuitable when the owner precipitated another move.

“THIS WILL RUIN EVERYTHING”—THE OPRY PLUGS IN

Electric steel guitars were introduced in the early 3333s and became popular in western swing bands and big bands where acoustic

instruments had to do battle with larger ensembles. One electrified instrument would have created an imbalance in the early

Opry groups, but that wasn’t the reason they weren’t on the show. Judge Hay was dead set against them, and his opinions were

shared by many within the Opry cast. If Hay was a pioneer, he was also a purist, and saw no contradiction there.

PEE WEE KING:

We proved that country music doesn’t have to sound old-timey. The first time Judge Hay heard me play my accordion, he said,

“What is that thing?” I said, “It’s an accordion.” He said, “That’s not a country instrument.” Every time we’d introduce a

new instrument on the Opry, Judge Hay would get upset. His glasses would come down on his nose. He would call me over, and

I knew I was in for a lecture. That’s what he did when we did a show with a drum for the first time. He said, “Pee Wee, there’s

no room on the Opry for that.”

Pee Wee King with the offending accordion.

SAM M

C

GEE:

Fellow by the name of McLemore had this electric steel guitar. I heard him play the thing and I thought it was pretty. Never

heard one before, so I bought it offa him. I got by with it for two Saturday nights on the Opry, and on the third I was ready

to play on our half hour, and Judge Hay came out and tapped me on the shoulder.

BASHFUL BROTHER OSWALD:

Judge looked at it, and he said, “We’re not ready for that thing yet, sonny boy. Take it back home.”

Ernest Tubb’s electric guitarist, Jimmie Short, didn’t make the journey to Nashville, and Harold Bradley subbed for him in

this 1943 shot. Toby Reese is on bass.

ROY ACUFF:

This will ruin everything.

KIRK MCGEE:

It wasn’t too long after, Judge Hay was gone. Then they had electrified instruments in every band.

JUSTIN TUBB:

My dad started using the electric guitar so people could hear him in the honky-tonks where he worked. He delivered beer for

a company out in west Texas, then he’d get up and play for tips, and you couldn’t hardly hear him over the drunks. Some of

those west Texas honky-tonks can be kinda noisy.

GRANT TURNER:

It was 1943 when promoter Joe Frank insisted that his new star, Ernest Tubb, be allowed to use electrified instruments. He

would not have sounded like his records otherwise.

DAVID STONE:

The owner of the tabernacle on Fatherland got fussy and wanted a big cut, so we had to move on.

HARRY STONE:

I don’t remember who was governor of Tennessee at the time, but I went to see him and asked permission to use the War Memorial

Auditorium just across the street from WSM’s offices. Despite the ruling against commercial use of the facilities, I convinced

him this was art and culture and [in July 1939] he let us have it.

PEE WEE KING:

When we arrived at the Opry in 1937, admission was still free. People would arrive early and eat dinners they’d brought from

home on the ground. [My manager] Mr. Frank was looking out at the throng of people waiting for the show to start, and he said

to David Stone, “You’re missing the boat. You should charge a small admission. Maybe a dime or a quarter.” Mr. Stone said,

“Why should we charge? We’re getting a lot of valuable advertising out of these free shows.” Mr. Frank said, “When you give

something away, people don’t value it as much as they should, but if you charge even a small amount, they know it’s something

special.”