The Grand Ole Opry (30 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

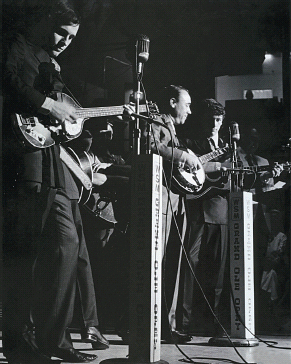

Lester Flatt (left) with Louise and Earl Scruggs.

The

Esquire

article by folklorist Alan Lomax appeared in October 1959. Lomax coined the phrase “folk music in overdrive” to describe

bluegrass. Late the previous year, the Kingston Trio had taken an old mountain song, “Tom Dooley,” and made an international

pop hit out of it. “Tom Dooley” ignited a folk craze on campus, and Lomax’s article refocused interest on bluegrass as a repository

of American folklore. At first listen, bluegrass appeared to have been unaltered for hundreds of years; in fact, of course,

Bill Monroe had formulated the style just fifteen years earlier. Some of the songs were ancient, but many more were modern.

Flatt and Scruggs sensed an opportunity, and on LPs like

Folk Songs of Our Land,

began tailoring their repertoire to their new audience. For one thing, college students bought LPs, not singles, and quite

suddenly bluegrass LPs didn’t sell only eleven thousand copies anymore.

Bill Monroe felt slighted, and when Ralph Rinzler, then a student at Swarthmore College, asked him for an interview, he snapped,

“If you want to know about bluegrass, ask Louise Scruggs.” But Rinzler persisted and eventually took over Monroe’s management.

RALPH RINZLER:

Recognition for bluegrass and for Flatt and Scruggs as its significant exponents began with Scruggs’ 1959 appearance at the

Newport Folk Festival, followed by Flatt and Scruggs’ joint appearance in 1960. It was February 1963 that Bill made his first

college appearance at the University of Chicago Folk Festival, followed by his first New York concert appearances and his

first folk club date at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles. Bill Monroe became the patriarch of bluegrass just as his rural and

urban followings began to come together at festivals and concerts, united tenuously by their love for his music.

SHARON WHITE

of the Whites:

Those festivals started, and you could tell that there were many bluegrass groups that Bill wasn’t approving of. It worried

me. I thought, If he doesn’t let go of this music, he’ll choke it to death.

RALPH RINZLER:

That he didn’t smile on LP jackets is wholly consistent with his personality and symbolizes the degree to which he held himself

apart from those around him, musically, socially, and personally. A man more easily persuaded would likely not have succeeded

in so formidable an undertaking as bucking the rushing cultural and economic tide of the country music industry.

Flatt and Scruggs’s career received a considerable boost from the television series

The Beverly Hillbillies.

They backed Jerry Scroggins on the show’s theme song, “The Ballad of Jed Clampett,” and their version became a hit single.

The show’s writer/producer later brought them onto the show for cameo appearances, boosting their profile yet again.

LESTER FLATT:

That song wasn’t our favorite, but we learned to love it when it hit number one on the trade charts. Working with

Beverly Hillbillies

is different from what we’re used to. On our own TV show for Martha White, we cut three or four shows as fast as we can. Out

there, it takes them a week to cut a thirty-minute film.

Lester Flatt with Granny in a

Beverly Hillbillies

publicity shot.

A new record producer wanted them to record Bob Dylan songs and other contemporary material. Scruggs embraced the challenge;

Flatt did not. Success had enabled Flatt and Scruggs to set aside their artistic differences . . . for a while.

PAT WELCH,

journalist, in the

Tennessean:

On the night of February 22, 1969, when [Flatt and Scruggs were] supposed to perform at 10:15 on the Grand Ole Opry, Flatt

simply walked out without consulting Scruggs. Since that occasion, Flatt has not spoken to Scruggs, and the next information

Scruggs had concerning him was on February 25 when he was advised that Flatt was trying to obtain bookings through an agency

in violation of his contract with Scruggs Talent Agency. Scruggs charged that Flatt lived on his [Flatt’s] farm in Sparta,

Tennessee, since 1960 and devoted a minimal amount of time to the business of the partnership. On some occasions, Scruggs

said he had to use tapes on road trips to familiarize Flatt with the new material.

After Flatt and Scruggs broke up, Earl Scruggs formed a revue with his sons Gary (left) and Randy (right).

After the rift, Lester Flatt returned to traditional bluegrass, and, in 1971, set aside longstanding differences with Bill

Monroe. Although they both played on the Opry, they had managed to avoid speaking to each other since 1953, but backstage

at the Opry one night Monroe sent his son, James, to ask Flatt if he would play at Monroe’s Bean Blossom Festival. Marty Stuart,

who had joined Flatt as a thirteen-year-old mandolin player, recalled the historic reunion.

MARTY STUART:

Bluegrass festivals were becoming a big thing. You’d see the Woodstock generation, mom and pops, bikers. Bean Blossom was

a major event, and Lester played there in 1971. Everyone knew there had been a row, but then Lester came out and did a duet

with Bill Monroe on “Will You Be Loving Another Man.” The crowd went berserk. John Hartford told me he watched it and bawled

like a child.

Lester became a rock star. We started working college campuses a lot. The first show was Michigan State. Gram Parsons and

Emmylou Harris opened for us. The Eagles were out touring with “Desperado” then, and Bernie Leadon wanted to meet Lester.

Lester said, “Aw, this ain’t gonna amount to nothin’.” But it did. I don’t really know what Lester thought about that crowd.

He and Earl had played for a lot of hippies in the sixties. It wasn’t brand-new to him. The hippies loved him. He didn’t get

what they were about, but he understood applause and he understood ticket sales and he understood encores.

Lester Flatt with Marty Stuart and the Osborne Brothers, 1975.

Ten years passed without much, if any, communication between Flatt and Scruggs.

MARTY STUART:

Spring 1979, Bob Dylan was playing Nashville. When I was introduced to him, he said, “Aren’t you the kid that plays mandolin

with Lester Flatt?” I said yes. Dylan asked, “How is Lester, anyway?” I said, “He’s dying.” He wondered if Lester and Earl

talked anymore. I told him I didn’t think so. He said this was sad because Abbott and Costello were always going to speak,

but they never got around to it before one of them died. Dylan kind of left it at that, but I went up to a payphone and called

Earl and asked him if I could come talk with him. When I got there, I told him that the end was real soon for Lester and I

wished he would consider going to see him one last time. Scruggs did, and that’s just one more reason why I love him.

The bluegrass revival broadened into a revival of traditional country music. At the forefront of this revival was the Nitty

Gritty Dirt Band’s three-LP set,

Will the Circle Be Unbroken,

which paired the rock ’n’ roll band with traditional artists and songs. Although Bill Monroe pointedly refused to be a part

of the album, it succeeded in reconciling rock musicians with heritage artists like Roy Acuff. At the same time, there was

a growing acknowledgment of the Opry’s role in preserving and showcasing vintage country music. Most nights at the Opry, fans

could still see the entire history of country music represented.

Other older artists—often to their surprise—found a new audience within the counterculture.

ERNEST TUBB:

When the hippies first started coming up to me, I was a little apprehensive, but they’ve turned out to be some of my biggest

fans. These kids are looking for down-to-earth realism. They’re looking for something our country’s lost over the years. They’re

sincere, and they could be more right than a lot of the rest of us. I don’t mind long hair as long as it’s clean, and all

my hippie fans have been clean and well-behaved.

G

RAND

O

LE

O

PRY

NEW MEMBERS:1970s

J

ERRY

C

LOWER

L

ARRY

G

ATLIN AND THE

G

ATLIN

B

ROTHERS

T

OM

T. H

ALL

D

AVID

H

OUSTON

J

AN

H

OWARD

B

ARBARA

M

ANDRELL

R

ONNIE

M

ILSAP

J

EANNE

P

RUETT

D

ON

W

ILLIAMS

T

AMMY

W

YNETTE