The Grand Ole Opry (29 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

HAL DURHAM,

Opry announcer and later manager:

For many years, the Opry manager was a part of the radio station staff, and the Opry was simply another program of the radio

station. It was not a separate entity. It was just another live music program. Up until the 1960s, WSM had live classical

music, live pop music, and the Opry. The manager of the Opry was also a program staff member of WSM. Only after Bud Wendell

took over the management of the Opry in 1968 did the Opry become a separate entity. Then the manager of the Opry reported

to the president of National Life.

JACK D

E

WITT:

Bud Wendell was my executive assistant. When I retired in 1968, Irving Waugh took over as president of WSM. He fired Ott Devine

as manager of the Grand Ole Opry, and he made Bud Wendell in charge of the Opry. Irving was always afraid of Bud Wendell.

He was afraid that I would make Bud president of WSM, but I didn’t do it because Irving had been vice president and ought

to be promoted. Bud called me and said, “Jack, I’ve been put aside. I’m in charge of the Grand Ole Opry. What should I do?”

I said, “Bud, it’s the best thing in the whole company. Just hang in there and do it,” and he became very good at it.

Bud Wendell cuts the Opry birthday cake, 1969.

JEANNIE SEELY:

Bud Wendell developed a vision for the Opry, a very important vision. Bud had a strong business background, but he came to

understand what made it click between us and the audience. He was easy to work with. During that time, we had the credit system

where you had to work a certain number of dates at the Opry to earn credits or be suspended. One year, Jack Greene and I were

out on the road together. We were both on the charts, and we were working all the time. I got to figuring out what we had

on the books and we were going to come out a credit and a half short. I went in to talk to Bud and asked him if we could make

up this credit after the first of the year. He just listened and raised his eyebrow, and he said, “You tried, and I think

we can bend the rules here. We’ll see what next year brings.” He knew that sometimes you couldn’t go strictly by the rule

book, and he knew we were sincere.

Bud Wendell’s vision would take the Opry into the twenty-first century, but, one month after he took over, the man who’d had

the original vision for the Opry died. On May 11, 1968, at 10:00 p.m., Opry announcer and Hay protégé Grant Turner, along

with the rest of the Opry, paid tribute to founder George D. Hay, who had passed away three days earlier.

GRANT TURNER:

George Hay not only created the Opry out of the fabric of his imagination, he nurtured and protected it during its formative

years. He heard the heartbeat of a nation in the country music he loved. He taught us to measure our music by this golden

yardstick: it must be eloquent in its simplicity. He called himself the Solemn Old Judge. If he was solemn, it was only to

the face of those who sought to change or corrupt the purity of the barn dance ballads he sought to preserve. We, the performers

and friends of the Grand Ole Opry, salute the memory of one whose influence is felt on the stage of the Opry tonight—the Solemn

Old Judge, George D. Hay.

Among other contributions to the country music community, Bud Wendell (left) launched Fan Fair.

Five months later, on October 8, Judge Hay’s longtime nemesis, Harry Stone, died. The last years weren’t good for either of

them. Judge Hay felt that the Opry had turned its back on him and his concept of the show. He left Nashville and died in Virginia.

Harry Stone had returned to Nashville to help start the Country Music Association, but was working as an advertising salesman

for a magazine published by the Tennessee Electrical Cooperative Association at the time of his death.

And then, on June 26, 1969, WSM’s founder, Edwin Craig, died. The three men who had steered the Opry through its earliest

years had died within thirteen months of each other.

“ALL MY HIPPIE FANS”—THE BLUEGRASS REVIVAL

O

pry stars like Bill Anderson and Marty Robbins were in the pop charts, and the “Nashville Sound” was on everyone’s lips. No

one quite knew what the “Nashville Sound” was (producer Chet Atkins famously rattled his change when asked), but everyone

knew what it

wasn’t.

It wasn’t bluegrass.

Country music had irrevocably changed, but bluegrass hadn’t and wouldn’t. Until the mid-1950s, bluegrass records had been

played alongside other country records and bluegrass stars toured alongside country stars, but, as country music changed,

blue-grass held fast to its old ways and distanced itself from country music. Several blue-grass artists, including the Stanley

Brothers, lost their major-label deals, and the music retreated to smaller record labels, smaller stations, and smaller venues.

Only Flatt and Scruggs were doing well, while Bill Monroe struggled along with everyone else.

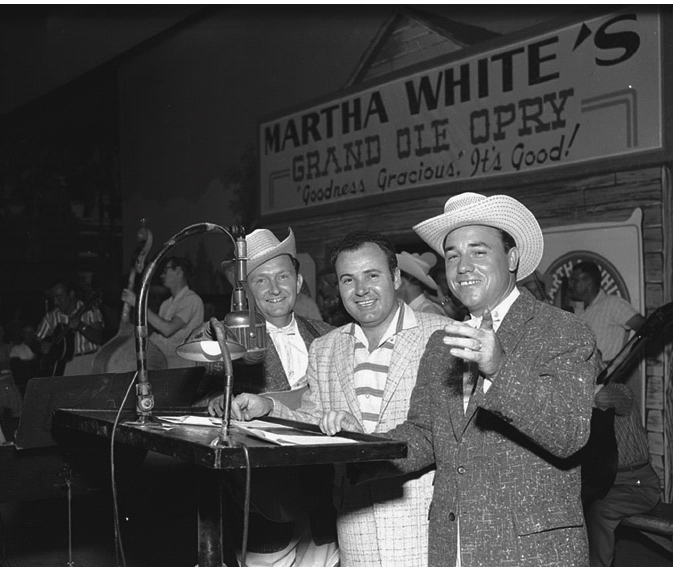

Lester Flatt (left) and Earl Scruggs (right) on stage for Martha White with announcer T. Tommy Cutrer.

KENNY BAKER,

Bill Monroe’s fiddler player:

There was a few years there, about the time this rock ’n’ roll came in. It wasn’t only bluegrass music, but all of country

music shot its wad. Why they just disbanded left and right there in Nashville. Bill kept an outfit going, but he damn sure

didn’t make no money with it.

BUCK WHITE

of the Whites, Opry stars:

I saw Bill Monroe in Wichita Falls right around that time. He could only afford to bring two men. We got a boy from the Light

Crust Doughboys to play banjo with him, and you gotta believe he played a different kind of banjo. But Bill put on a show.

He never complained. He was sufferin’ along with a lot of others.

RALPH RINZLER,

musicologist and later Bill Monroe’s manager:

Bill Monroe was in the dumps because of rock ’n’ roll. Another factor was that Flatt and Scruggs had cornered the market on

what was left. Bill was left behind because he stuck hard with what he believed in, and he had no business organization behind

him. Mrs. Scruggs managed their business and gave the impression that bluegrass began and ended with Flatt and Scruggs.

Although it was commonly believed that Bill Monroe hadn’t spoken to Flatt and Scruggs since the duo left his employment in

1948, they’d worked together in the early 1950s, and it wasn’t until Flatt and Scruggs’s sponsor, Martha White Flour, began

pressing for the duo’s inclusion on the Opry that the fallout occurred.

JAKE LAMBERT,

bluegrass musician:

Knowing WSM always paid attention to the amount of mail a group could pull, Cohen Williams [of Martha White Flour] collected

a huge mail bag full and took it to WSM. He dumped it out on the office floor of Jack DeWitt. Either they put Flatt and Scruggs

on Martha White’s half hour of the Opry or he would pull his company’s advertising off the station.

Bill Monroe’s case was that the Opry wouldn’t hire someone who sounded like Roy Acuff or Ernest Tubb, so they shouldn’t hire

another bluegrass act. He tried to get up a petition to keep Flatt and Scruggs off the Opry, and insisted that his sidemen

not talk to Flatt and Scruggs or their sidemen. It wouldn’t be the last time Bill Monroe acted in that way, but while others

like Flatt and Scruggs edged the music in new directions, Monroe kept it pure and simple for future generations.

Surviving Nashville. Bill Monroe on WSM-TV with host Smilin’ Eddie Hill to his left.

RICKY SKAGGS:

If it hadn’t been for Bill Monroe and his tenacity, bluegrass music might have died. He set his face like flint. He kept it

alive. Flatt and Scruggs took the music onto television, but Bill Monroe’s hang-in-there-like-a-rusty-fishhook attitude really

kept the music alive. He survived rock ’n’ roll, and he survived Nashville.

In the late 1950s, few would have given good odds on the survival of bluegrass; it was hard to find on the radio and on records.

But it not only survived; it found an entirely new audience, an audience that most Opry stars hadn’t even thought about.

RALPH EMERY,

WSM deejay:

Sonny Osborne told me that there used to be eleven thousand bluegrass fans in the United States. I asked him how he knew,

he said, “We recorded bluegrass for years and we sold eleven thousand copies every time out.”

Look

magazine, August 27, 1963:

Serious students of folk music, always seeking genuine ethnic sources, are rediscovering the spirited “Blue Grass” style,

which is perhaps closer to the majority of Americans than any other musical form.

DOUG GREEN

of Riders in the Sky, Opry stars:

I was in college in the sixties, and we played bluegrass. There was something so plaintive and approachable about it. When

you’re nineteen, you haven’t seen your share of honky-tonks and broken hearts. The country music experience you find in those

kind of songs is remote, but songs about the mountains, missing home, and the straightforward honesty of the emotions resonated

with a lot of college-age kids.

SHARON AND CHERYL WHITE

of the Whites, Opry stars:

The kids weren’t about materialism. They looked for something honest and real, and bluegrass was it. You can’t help but be

drawn to it. The purity of it. Louise Scruggs managed Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, and she was the one who began booking

Lester and Earl into campuses. They said it couldn’t be done, but she was right.

D. Kilpatrick was still in charge of the Opry in 1959 when Louise Scruggs called him because she’d received some interest

from college campuses. Opry stars had never played campuses; in fact, never even thought of playing there.

D. KILPATRICK:

Louise told me that Davidson College in North Carolina had called them and wanted to schedule a performance on campus, and

she wanted to know if they should do it. I said, “What do you mean whether?” She said, “Well, we don’t want anyone laughing

at us.” I said, “They’re not going to laugh at you.” It wasn’t three months and they were over at Duke University. Then before

long that

Esquire

magazine article came out on them.