The Grand Ole Opry (37 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

MICHAEL MCCALL,

journalist, in the

Nashville Banner:

A typical live Opry broadcast in 1957 might feature current hits by Kitty Wells, Hank Snow, Ray Price, Jim Reeves, Faron Young,

Webb Pierce, Marty Robbins, the Everly Brothers, and a dozen other leading hit-makers. [This year] 1987, a Saturday night

roster at the Opry bears little resemblance to a Top 40 chart. On February 7, for instance, the line-up included only one

act—the Whites—that had achieved a major hit in the 1980s. Today, with television, video, and other means of promoting a new

act, live radio does not carry the same strength. And the discrepancy between the Opry’s modest stipend and the income from

a solo concert has grown ever larger.

The Ryman Remembered. From left: Pee Wee King, Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, Minnie Pearl, Grandpa Jones, Little Jimmy Dickens,

and Grant Turner.

HAL DURHAM:

Of course, the Opry doesn’t have the impact on careers that it once did. At one time, the Opry represented the only game in

town. Today, the artist has a lot of other doors open to him or her, mainly through the business of records. When the Opry

was booming in the 1930s and ’40s, the record business, especially country records, was very limited. Very few stations played

country records, except at odd times, like five o’clock in the morning. Today, with thousands of country radio stations, it

has opened the doors to so many people, and the Opry, as a live music place, is rare. So the Opry isn’t the only game in town

any more, but it is the only game in town that can offer that tradition, going back to the roots. Hank Williams, Patsy Cline,

Red Foley, Roy Acuff. My experience has been that, at every show at the Opry, those spirits are there.

BUD WENDELL:

When road dates got so lucrative, you couldn’t ask an act to come in and play the Grand Ole Opry for $100 or $200 when they

were making $20,000 or $30,000, and now they’re making $100,000, so it now becomes a situation, in my judgment, where, if

they really want to be part of the tradition or the family, they’ll cut out enough dates, or balance their schedule, where

they’ll be there on Saturday nights and make it worth their while and worth the Opry’s while.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, country music and the Grand Ole Opry were reinvigorated by artists with a deep respect

for all that the Opry represented. Emmylou Harris and Ricky Skaggs had kept tradition-based music alive through some lean

times, but suddenly they were joined by Randy Travis, Reba McEntire, Vince Gill, Clint Black, Patty Loveless, Alan Jackson,

Marty Stuart, and Garth Brooks. These new artists didn’t

need

the Opry as earlier generations had, but

wanted

it for all it symbolized.

RICKY SKAGGS:

Mister Acuff said something to me the night I joined the Opry. He said, “Yeah, we’ll make you a member, but you’ll never show

up. You’ll be like all the rest of ’em.” And I said, “I’m gonna make you eat those words.” And so every weekend I was at the

Opry, I’d knock on his door, and I’d say, “Hey, Mister Acuff, I’m here again.” Finally, it got to a point where he said, “I

don’t want to hear it anymore.”

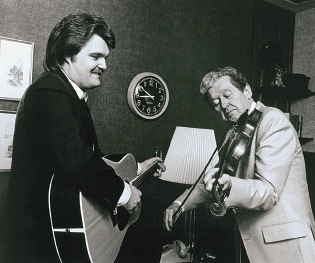

Ricky Skaggs picks with Roy Acuff backstage.

STEVE BUCHANAN,

president of the Grand Ole Opry Group:

There was one time that Vince Gill played on Roy Acuff’s portion of the Opry. Vince was singing “When I Call Your Name,” and

Roy Acuff was sitting off to the side on a stool. Roy was listening so intently to Vince, and tears were running down his

cheeks. It spoke to his love of the music. He was very unselfishly engaged in the song. To me, that perfectly symbolizes the

Opry, handing it down from generation to generation.

Garth Brooks joined on October 6, 1990, the same night that Alan Jack-son first appeared on the show. Introduced by Johnny

Russell, Brooks performed “Friends in Low Places,” “If Tomorrow Never Comes,” and “The Dance.”

CAROL LEE COOPER,

Opry star:

Garth Brooks said that when he went out there it was so touching to stand in that circle where all of these people had stood

before, people that are no longer with us, and he said that all he could do was stand there and cry. Johnny Russell was the

one who introduced him that night, and Garth said, “I’ll never forget Johnny Russell for this. He hugged me, and put the microphone

down at his side where no one could hear what he said, and he said, ‘Just enjoy it. Enjoy the moment.’ ”

HAL DURHAM:

There was an occasion in the 1960s at the Ryman when the audience reacted to a performance by Johnny Cash. They stomped their

feet on those wooden floors, and the sound of a full house stomping their feet on those floors was unbelievable. When we moved

to Opryland with its concrete floors, it was a whole different sound. But there was one time when Garth Brooks appeared. He’d

been on the Opry for a good while, but he had a period of achieving great success very suddenly. And he came back to the Opry

for the first time after maybe a couple of big records, and the noise in the Opry House reminded me of the noise I’d heard

at the Ryman in the 1960s.

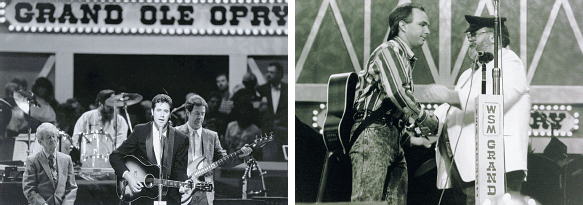

left: Roy Acuff looks on as Vince Gill performs.

right: Johnny Russell inducts Garth Brooks.

ROY CLARK

to the Opry audience, following Garth Brooks:

Twenty years ago, your mothers used to scream like that for me.

The new members joined the Opry just in time for the older members to pass the torch. Grant Turner died on October 14, 1991,

and the following year the Opry lost one of its most iconic performers.

JAY ORR,

journalist, in the

Nashville Banner:

On its 67th anniversary broadcast Saturday night [November 30, 1992], the Grand Ole Opry family mourned the passing of a stalwart

and celebrated the arrival of an exciting new member. A holiday weekend capacity crowd joined the Opry in marking the passing

of Opry legend Roy Acuff and in welcoming new member Marty Stuart. Opry manager Hal Durham said, “This is an evening of great

personal sadness for us all. For the first time in 54 years, the Grand Ole Opry will be going on without Roy Acuff. It will

simply never be the same without him, and there is no way to replace him. But while we will miss his presence, his music and

his spirit will forever be a part of this show.” Jimmy Dickens presided over the evening’s brightest moment, the televised

induction of Marty Stuart as the 70th [active] member of the Grand Ole Opry. He was announced as being the 71st member before

Acuff’s death.

MARTY STUART,

press conference, November 1992:

There’s a brand-new crop of country fans that haven’t a clue about the Opry. I think it’s our job to recruit ’em and introduce

them to how great the Opry can be. I worked the Opry with Lester Flatt, but I left the show when Lester died in 1979. I called

Hal Durham and told him that the prodigal son was ready to return. I’ve talked to

Saturday Night Live

bandleader G. E. Smith and

Letterman

bandleader Paul Shaffer, and I’m finding that people like that have always died to play the Opry, but never had a reason or

been asked. Hal’s agreed to let people like that come out and sit in with me.

Minnie Pearl had suffered a stroke in 1991; she died on March 4, 1996. Her husband didn’t tell her of Acuff’s passing.

When Bill Monroe was asked “Who will lead bluegrass music into the twenty-first century?” he replied without a moment’s hesitation:

“I will.” He knew, though, that his prodigious energy was failing, and he died on September 4, 1996, knowing that the music

he’d done more than anyone to create was more popular than at any time in its history.

BILL ANDERSON:

Mister Monroe mellowed a lot. I think he finally found that what he’d created was accepted and honored. He realized that it

had all been worthwhile and was justified. That served to mellow him tremendously. It was a complete metamorphosis, and it

was fun to watch. In earlier days, I’d pass him in the hallway backstage and I’d say hello and he’d walk right by you, but

it got to where he’d kid with you, and he’d put a quarter in your hand after you’d performed. He could put aside some of the

old animosities.

An all-star bluegrass band, including the Osborne Brothers, Earl Scruggs, Jim and Jesse, Bill Monroe, the Whites, Ricky Skaggs,

and Patty Loveless.

SHARON

and

CHERYL WHITE

of the Whites:

Ricky [Skaggs] played commercial country music but tried to show the bluegrass influence. He was competing with whatever was

on the radio, but he had Bill Monroe in the videos, and Bill began to appreciate that. Then when the Kentucky Headhunters

did his song “Walk Softly on This Heart of Mine,” the royalty checks made a believer out of him. It showed you could take

bluegrass and make something commercial out of it, just like Elvis had done thirty years earlier. They put us in a dressing

room with [Bill] at the Opry. We were on MCA Records then, and he’d pitch songs to us. He’d say, “Listen to this. Sing with

me.” We’d never heard it before! But when Bill Monroe says, “Sing with me,” you try. We’d watch his mouth, and try our best.

RICKY SKAGGS:

Seeing people like me and others showing him respect really started to break down some of the walls he’d put up for protection.

He was a very shy and very lonesome person, and I just pushed my way into his life. I think the love that I and Marty Stuart,

Vince Gill, Patty Loveless, and others showed him began melting a lot of the coldheartedness he’d had. Then he had open-heart

surgery, and that’ll get your attention. I’d go over to his place, and we’d just play for three or four hours. He’d listen

to me and he’d see that the music was going to live. Before he died, I promised him that I would tell the story of him and

his life and his music. He was able to rest after that. I told him that the music was much bigger than him.

His funeral was a sad day but a happy day. It was at the Ryman, and it was one of those moments that only seem to happen at

the Ryman. There’s a scripture in the Bible which says that if the seed does not die and fall to the ground, it cannot produce

fruit some thirty, some sixty, some hundredfold. Me and Marty and Vince Gill had been out to sing “Angel Band,” and we came

backstage. There was a digital clock backstage, and I looked at it. It had 11:11 on it. That number has followed me. So many

times, I’d look at a clock and it would be 11:11. The way a digital clock reads, it looks like a scripture. Eleventh chapter,

eleventh verse. There was an illumination around it, and I felt that my heart was being pulled toward that. I said to Marty,

“That’s a scripture. I’m gonna look that up.” God is trying to tell all of Mister Monroe’s seed something. We’d sung all these

somber songs—“Angel Band,” and so on—and Marty looked at me, and said, “Don’t you think we ought to send him home with a celebration?”

I said, “Absolutely.” He said, “Let’s do ‘Rawhide,’ ” and I said, “Yeah!” We got out there and played “Rawhide” at six hundred

miles an hour. I said to everyone, “If you have a problem with this, get over it. This is to honor Bill Monroe.” The place

came unglued. It was like you’d put an electric shock in every seat. It was a holy experience. When I got home, I got my Bible

out, and looked at different scriptures. I looked at Isaiah, chapter 11, verse 11. It says, “And it shall come to pass in

that day that the Lord shall set his hand again the second time.” Second time, you see. You can look, but from 1996, bluegrass

music has turned somersaults. It has grown and become so popular. People say, the revival in this music started with [the

film

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

]. Wrong!

O Brother

didn’t fire up our music. Our music fired up

O Brother.

When Mr. Monroe died, I felt that it was time for me to give up my career in country music and take my place at the table

to play this music I’d grown up playing.