The Grand Ole Opry (31 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

“THE OPRY WAS A COMFORT”

O

ften, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it seemed as if the nation was polarized to the point that it might disintegrate

into civil war. An institution such as the Grand Ole Opry had to take its stand. In November 1969, President Nixon made a

televised speech about Vietnam. Concluding, he called upon “you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans,” and the

Opry would entertain that silent majority. It would conjure up images of a more harmonious time and place, and its adaptation

to social and musical changes would be measured.

BILL ANDERSON:

The Opry wasn’t cutting edge. It wasn’t designed to be cutting edge. The Opry was comfort. It took people’s minds off protests

and riots. It was a refuge for people who weren’t caught up in the upheaval that was going on.

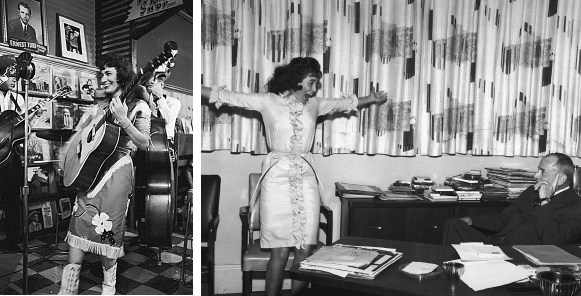

Charley Pride at WSM’s forty-first birthday celebration in 1966.

MINNIE PEARL:

In an insecure world, the Opry doesn’t change. Our jokes, many of our songs, and the customs we portray stay the same. People

like it because it gives them a sense of security, a happy recollection of the way they were told things used to be in the

good old days.

Nevertheless, change made its way to the Opry’s door. Charley Pride became country music’s first African American star since

DeFord Bailey, and several groups, including the Byrds and Flying Burrito Brothers, blended sixties’ rock with traditional

country music. Just as Elvis gave the Opry audience of October 2, 1954, a sneak preview of rock ’n’ roll, so the Byrds provided

the Opry audience of March 15, 1968, with a preview of country rock. No one in the audience or even onstage could have foreseen

it, but the Byrds and Burritos would influence the Eagles and many southern-rock bands, and those bands in turn influenced

country music in the 1990s and beyond.

In March 1968, the Byrds were in Nashville to record what many regard as the first country-rock album,

Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

They asked for a guest spot on the Opry, believing the audience would embrace their music.

ROGER MCGUINN,

leader of the Byrds:

[Group member] Gram Parsons figured we could win over the country audience. He figured that once they dig you, they never

let you go. So we were shooting for the Opry. We even played there. First rock group ever to do so. Columbia Records had to

pull some strings to get us on the bill.

Opry band members Jimmy Capps and Hal Rugg observe as the Byrds—Kevin Kelley, Gram Parsons, Roger McGuinn, and Chris Hillman—make

their Opry debut.

EMMYLOU HARRIS,

Opry star and Gram Parsons’s duet partner:

Gram wanted to be a country artist. He really wanted to bring country music to his generation and he wanted to be accepted.

There was that country boy yes-ma’am, no-sir about him. I think he wanted to be accepted by the Grand Ole Opry because it

meant a lot to him. But he never got accepted. They were just too rock ’n’ roll.

RANDY BROOKS,

journalist, in the

Vanderbilt Hustler:

The Byrds of “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Turn, Turn, Turn,” and “Eight Miles High” fame were in last minute preparation for their

Grand Ole Opry debut. An unidentified man suggested that, for the sake of public relations, they use the current number one

song, “Sing Me Back Home,” for their encore. The boys had other ideas, and even after the MC introduced that song, guitarist

Graham [sic] Parsons began to play “Hickory Wind,” a very pretty and very country tune. In performance the Byrds were a far

cry from their earlier days. The unbearable volume of amplified instruments, which has impaired the hearing of stalwart Byrds

fans in the past, was gone. In its place was the lazy twang of steel guitar and three very pleasant voices, actually audible

over the accompaniment. Both “Hickory Wind,” and “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” drew polite but unenthusiastic response from an

audience which only minutes before has cheered heartily for the Glaser Brothers and displayed unabashed adoration for Skeeter

Davis. Following their appearance at the Opry, the Byrds came to Vanderbilt. The studios of WRVU were crowded with onlookers

as each member of the group played disc jockey and answering service during an informal interview conducted by Gary Scruggs

and Speed Hopkins. In reply to a telephoned question, Parsons said that he feels that the next sound in pop music will be

an “exploitation of country music.” One caller who accused the Byrds of being “dirty Commies” turned out to be group member

Chris Hillman phoning from downstairs.

Less than one month later, Opry audiences were forced to confront the turmoil of the late 1960s head-on. On April 4, 1968,

Martin Luther King was killed and riots erupted spontaneously in 130 cities.

The

Tennessean,

April 6–7, 1968: Opry to Miss 1st Live Program in Past 43 Years

The 7 p.m. curfew imposed by Mayor Beverly Briley interrupted the normal routine for thousands of the city’s residents, and

brought complaints from both negro and white. Several persons who phoned the Nashville

Tennessean

complained that they were frightened to go home from work because police officers were given the authority to stop anyone

on the street for questioning. One man called to say that the closing of bars and taverns put him on the wagon for the weekend.

Briley proclaimed a civil emergency existed in the city as a result of scattered violence in North Nashville. For the first

time in 43 years there’ll be no live Saturday night Grand Ole Opry. Instead of a live show, radio listeners will hear tapes

of past performances. The Opry would have performed for the 2204th consecutive time tonight.

Of course, the Opry had been canceled or preempted several times in its history, but this was the first and only time it was

canceled because of civil unrest.

BUD WENDELL:

Nashville was closed down. You just were not allowed out. The streets were to be cleared. I called [the mayor] and I said,

“I understand all this, but you must mean for everybody except for us,” and he said, “No, you’re included.” So we had no alternative.

We couldn’t get artists together, bands together, even if we had wanted to do something. There was no way for people to get

out. So we did the best thing we could. It was during that period of time that we had bomb scares. People would call schools

and businesses and say a bomb was going to go off in ten minutes, so we had a standby tape that we made ahead of time, and

we played that tape. It was a sad night, but we survived it.

Roy Acuff addressed the fans, many of them from out of town.

Friends, can I have your attention a minute. There’s something I’d like to say. We all know there’s a curfew on in Nashville.

It starts at seven o’clock, and there’s not going to be an Opry tonight. It seems a shame that so many people have come in

from out of town and won’t be able to see it. Let’s see if we can’t find a place and give them a show.

Roy Acuff brought the crowd to his museum on Broadway. Upstairs in a square dance hall, Acuff’s impromptu Opry started at

2:00 p.m.

At a time when many believed that the country was drifting toward anarchy, the senselessly brutal slaying of Grand Ole Opry

and

Hee Haw

star David Akeman, known as Stringbean, on November 10, 1973, seemed to bring the era’s troubles inside the Opry House itself.

BUD WENDELL:

String and Estelle had been there on Saturday night. I had coffee with them sitting around some of those little ol’ drugstore

tables I had put in there. These guys were out there ransacking the house and listening to the Opry knowing that they weren’t

going to get caught because they could hear Stringbean pickin’ on the show. I remember one thing String said. He and Grandpa

Jones were discussing their hunting expedition, and String looked at me and he said, “How y’all gonna make it around here

next week with both of us gone, Bud?”

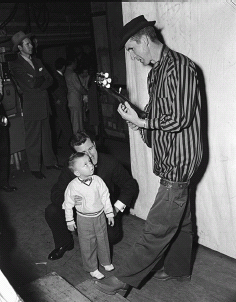

Stringbean

GRANDPA JONES,

Opry star:

The next morning, I was all packed for hunting and went over to pick up String. As I drove up the lane, I thought I saw a

coat lying about seventy-five yards in front of the house. When I got closer, I saw it was a person. I stopped the car and

went over. It was Estelle; she had been shot in the back and in the head. I felt her, and she was cold. I rushed to their

little house and hollered for String. His banjo he had played the night before was sitting on its side on the little porch.

I opened the screen. The other door was already open. String was lying in front of the fireplace. Shot in the chest. The phone

had been pulled off the wall, so I jumped in my car, drove to my house and called the Metro Police Homicide Division.

Stringbean had come home to find the robbery in progress and entered his house shooting.

BILL HANCE,

journalist, in the

Nashville Banner:

Stringbean was shot once and fell dead in the living room. Police said Estelle attempted to flee but was gunned down about

forty yards away, near a wooden cattle guard. The couple had lived on the farm 17 years and were extremely happy and content

living the simple life. They could have had more, but didn’t want more. Stringbean never drove a car; his wife did all the

driving. Roy Acuff stood staring at the little house where his longtime friend had been a shot a few hours earlier. “You know,”

he said, “String would sit in that chair over there and be content for hours just to look up at the top of the mountain watching

the birds, squirrels, and rabbits. I’ll tell you what the trouble is, the damn laws are too lax. The judges are too lenient

with criminals, and because of this the country is unsafe.”

There had been rumors that Stringbean didn’t believe in banks and kept a large amount of cash in his home, but the thieves

found nothing, nor did the police. John A. Brown and Marvin Douglas Brown were charged, and in October 1974, they were convicted

of Stringbean’s and Estelle’s murders. In 1996, twenty thousand dollars in cash was discovered behind a brick in the chimney

of the Akemans’ home. Marvin Brown died in jail in 2003, and John Brown was denied parole that year.

Lawlessness, civil rights, and Vietnam were just some of the issues that divided the nation in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

“Women’s lib,” as it was called at the time, was another. Tammy Wynette’s 1968 hit, “Stand by Your Man,” became a polarizing

record. Tammy, who had five husbands, might not have stood by her men for very long, but she certainly gave voice to those

who did. When she sang her song on the Opry stage, she was speaking for millions of women who weren’t burning their bras,

and for their husbands, who weren’t burning their draft cards. Even so, the Opry had to confront the issues raised by the

women’s movement. Change would be subtle and measured, but it would come.

Patsy Cline had changed the way women dressed on the show, and some of her songs hinted at a sexuality that might have shocked

or surprised earlier generations of Oprygoers, but Patsy didn’t live to see her protégé, Loretta Lynn, address burning social

issues head-on. Loretta not only saw a lot of changes on the Opry and in the entertainment business, but ushered in some of

them. Newly signed to Decca Records in 1960, she was billed as the “Decca Doll from Kentucky,” but within a few years no one

would ever be billed like that again. In 1966, at the Third Annual Conference on the Status of Women in Washington, D.C.,

the National Organization for Women was formed to campaign for equal rights. Two years later, protesters demonstrated in front

of the Miss America pageant. Loretta, though, brought controversial issues down to a personal, nuts-and-bolts level, allowing

her listeners to make up their own minds.