Read The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire Online

Authors: John Freely

Tags: #History, #Biography

The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire (25 page)

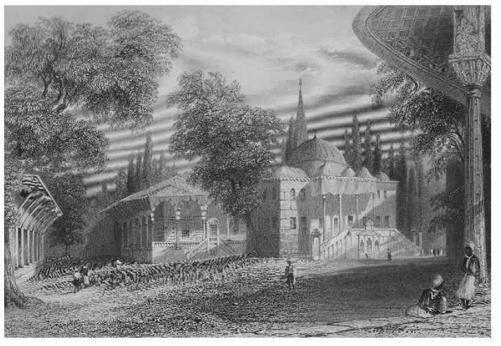

8b. Third Court of Topkapι Sarayι

When Mengli Giray tried to install Kirai Mirza as

tudun

in Kaffa there was strong resistance, particularly from Sertak’s mother, who bribed one of the Genoese committee, Oberto Squarciaficio, to support her son. Oberto put pressure on Mengli Giray by threatening to release his rebellious brothers, who had been imprisoned by the Genoese after they contested the khanate with him when their father Hacı Giray Khan died. Mengli Giray gave in and named Sertak as

tudun

, but most of the Tatar notables supported Eminek, and they sent an emissary to Sultan Mehmet asking him to intervene.

The Ottoman fleet left Istanbul on 20 May 1475 under the command of Gedik Ahmet Pasha, comprising 280 galleys, three galleons, 170 freighters and 120 ships carrying horses for his cavalry. The fleet reached Kaffa on 1 June, and on the following day it began bombarding the city. The defenders, most of whom were supporters of Eminek and favoured Turkish intervention, surrendered on 6 June, while Mengli Giray fled to his capital at Kekri with 1,500 loyal cavalry.

Gedik Ahmet had promised the townspeople that he would spare their lives if they paid the customary Ottoman

haraç

, or head tax. But in the next six days the conquerors seized all the wealth of the locals and plundered Kaffa, capturing some 3,000 of the townspeople as slaves. On 8 July Gedik ordered all the Italians in Kaffa, most of them Genoese, to board his fleet under pain of execution. The Italians were then resettled in Istanbul around the Seventh Hill of the city, where the census of 1477 recorded that they occupied 277 houses and had two churches.

Mengli Giray was captured and taken to Istanbul, where Mehmet pardoned him and sent him back to the Crimea as his vassal Eminek was installed as

tudun

in Kaffa, but now under Ottoman rather than Genoese rule. The Ottoman fleet then went on to capture all the other Genoese possessions in the Crimea, as well as the Venetian colony of Tana (now Azov) in the Sea of Azov. This ended the long Latin presence in the Crimea and its vicinity, which for the next four centuries remained under the control of the Ottomans, extending their dominions around most of the Black Sea.

That same year Malkoçoğlu Bali Bey led another Turkish raid from Serbia into Hungary, again plundering the countryside and killing or enslaving the local populace. A Hungarian force tried to cut the raiders off on their way back to Serbia, but Bali’s men virtually annihilated them, taking back several hundred severed heads that were sent to Sultan Mehmet in token of their victory. This seems to have provoked King Matthias Corvinus into mounting an expedition against the Ottomans, and on 15 February 1476 he took their fortress at Shabats in Serbia, capturing 1,200 janissaries, then advanced as far as Smederova, where he built three fortresses to blockade the city before he withdrew.

Mehmet himself led an expedition against Count Stephen of Moldavia in the spring of 1476. Hadım Süleyman Pasha led the advance guard, while the main army was commanded by Mehmet, a total of 150,000 troops, including a contingent of 12,000 Vlachs under Laiot Basaraba, whom the sultan intended to restore as voyvoda of Wallacha. Stephen commanded an army of 20,000 men, whom he positioned in a fortified wooded area on the expected Ottoman line of march, so that he could ambush them.

The two armies met on 26 July 1476 at the Battle of Rasboieni, during the first phase of which Stephen attacked the Ottoman vanguard under Süleyman Pasha. According to Angiolello, who was with the Ottoman army, Stephen’s troops charged out of the forest where they were hiding ‘and put Süleyman Pasha’s guards to flight… The Pasha mounted his horse and attacked. Some were killed on both sides but, because Süleyman Pasha had more men…, Count Stephen was forced to retire within his fortified wood, where he stood firm and defended himself with artillery, damaging the Turks, who withdrew to the outside.’

When Mehmet heard of this engagement he led the main army to attack Stephen, who tried to stop them with his artillery, but to no avail, as Angiolello writes in describing the course of the battle that ensued. ‘We put Count Stephen to flight, seized the artillery, and followed him into the wood. About two hundred were killed and eight hundred taken prisoner. If the wood had not been so dense and dark because of the height of the trees, few would have escaped.’

That effectively ended the campaign, as Tursun Beg notes in describing the aftermath of the battle. ‘The Prince [Stephen] fled and his camp was plundered by the Ottoman attackers. The Sultan pursued the fleeing Prince, pillaging and plundering his country and capital. Raids were carried out against Hungary, and then the army returned to Edirne laden with booty.’

Mehmet restored Laiot Basaraba as voyvoda of Wallachia, leaving him behind with his 12,000 Vlach troops. Matthias Corvinus sent an army into Wallachia after the Ottomans withdrew, and on 16 November 1476 the Hungarians deposed Laiot Basaraba and replaced him as voyvoda with the infamous Vlad III, the Impaler.

When Mehmet returned to Edirne he learned that Matthias Corvinus had invaded Serbia and blockaded Smederova by building three fortresses around the city. He realised the danger posed by the Hungarian incursion, and within ten days he turned his army around and headed for Serbia, ‘disregarding the fact that the soldiers and horses were exhausted by the journey and the hunger’, according to Angiolello.

When the Ottoman army arrived at Smederova the garrisons of two of the Hungarian fortresses around the city fled. But those in the third fort stood firm, and when the Ottomans attacked it they lost around 500 men. Mehmet then put the fortress under siege, which he knew he could not keep up for long because of the bitter winter weather. According to Angiolello, Mehmet had his troops cut down trees and throw them into the moat of the fortress until they were piled higher than its walls. He then prepared to set fire to the timber so as to burn down the fortress, but at that point the garrison agreed to surrender on promise of a safe conduct. Mehmet agreed, and for once he kept his word, allowing the 600 men of the garrison and their commander to leave the fort and set out on the road to Belgrade. Mehmet destroyed all three forts and then set his army back on the road to Istanbul.

Thus ended what came to be known as ‘the Winter War with Hungary’. Tursun Beg, after describing this difficult expedition, writes: ‘Out of consideration for the hardships to which his soldiers had been subjected during this winter campaign, in the following year, 882 [1477], Fatih did not go out on campaign.’

But, although Mehmet did not go to war himself in 1477, at the beginning of spring that year he sent Hadım Süleyman Pasha off on a campaign in Greece, his goal being to capture the Venetian fortress at Naupactos on the northern shore of the Gulf of Corinth. Süleyman’s forces besieged Naupactos for three months, during which time a Venetian fleet of twelve galleys under Antonio Loredano kept the city supplied with food and ammunition. Finally, after informing the sultan that he was unable to take the fortress, Süleyman lifted the siege on 20 June 1477, after which he returned to Istanbul. Mehmet then dismissed him as

beylerbey

of Rumelia, replacing him with Daud Pasha, who had been

beylerbey

of Anatolia, a post that was then given to Süleyman Pasha.

That same year Mehmet also sent an army of 12,000 men under Evrenosoğlu Ahmet to besiege the Albanian fortress city of Kruje, Skanderbeg’s old stronghold. The defenders were on the point of accepting surrender terms when a Venetian relief force arrived, forcing the Ottoman army to withdraw. The Venetians began plundering the enemy camp, but then the Ottoman army counter-attacked and defeated them, forcing them to take refuge within the fortress, which continued to hold out against the besiegers.

Meanwhile, a large force of Turkish

akincis

under Iskender Bey, the Ottoman

sancakbey

, or provincial governor, of Bosnia penetrated into Friuli beyond the river Tagliomento, which took them to within forty miles of Venice. The Venetian commander in Friuli, Geronimo Novello, gave battle to the

akincis

at the Tagliomento, but he and most of his men were killed. The Venetian chronicler Domenico Malipiero writes of the terror that gripped all of Friuli before the raiders suddenly withdrew.

There was great fear in the country. All the towns between the Isonzo and the Tagliomento were burned by the Turks. Three days after the battle, when they had collected the booty, the Turks pretended to leave. Then suddenly they turned round and put all the land on both sides of the river to fire and sword. Then, because there was a rumour that great preparations against them were in hand by land and sea, they collected their baggage and hastily left Italy.

The Venetian Senate decided to send 2,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry to Friuli, as well as arming an additional force of 20,000 troops to defend Venetian territory against Turkish raids. But the Turkish attacks continued nonetheless, one

akinci

force penetrating as far as Pordenone, pillaging and destroying everything in its path, the smoke of burning villages clearly visible to observers atop the campanile of the basilica of San Marco in Venice. According to Malipiero, the Venetian nobleman Celso Maffei cried out in despair to Doge Andrea Vendramin, ‘The enemy is at our gate! The axe is at the root. Unless divine help comes, the doom of the Christian name is sealed.’

The Senate decided in February 1478 that they would send Tomaso Malipiero as an envoy to Istanbul to seek a peace agreement with Sultan Mehmet. Tomaso returned on 3 May and reported that he had made no progress, since the terms proposed to him were unacceptable.

It soon became clear why Mehmet was not interested in a settlement, when word reached Venice that the sultan himself was leading an expedition against Shkoder, the Albanian fortress city whose capture had eluded him for years, along with Kruje. Gedik Ahmet Pasha had advised against trying to capture Shkoder, for he thought the fortress was invincible, and so Mehmet dismissed and imprisoned him, appointing Karamanı Mehmet Pasha to replace him as grand vezir.

Mehmet first stopped at Kruje, which Evrenosoğlu Ahmet had been besieging for a year, sending Daud Pasha on to Shkoder with most of the Rumelian army.

According to Angiolello, the defenders at Kruje had used up all their food supplies and had been reduced to eating cats, dogs, rats and mice, but still they would not give in. On 15 June 1478 the defenders sent emissaries to Mehmet to negotiate terms of surrender, and he agreed to give safe conduct to all who wished to leave and to allow those who remained to live in Kruje as Ottoman subjects. But when they surrendered only those who could pay a large ransom were allowed to leave unharmed, all the rest being beheaded. Mehmet then took possession of Kruje, thereafter known as Akhisar, which thenceforth remained in Ottoman hands until 1913.

Meanwhile, Daud Pasha and his Rumelian army had reached Shkoder on 18 May. They were joined there on 12 June by the Anatolian army under Mesih Pasha, the new

beylerbey

of Anatolia, brother of the late Hass Murad Pasha. The Ottoman artillery, which had been transported by camel caravan, was in place by 22 June, when the siege of Shkoder began with a heavy bombardment of the fortress.

Mehmet arrived from Kruje with his contingent on 2 July, by which time Shkoder had been bombarded daily by the artillery, while the Ottoman archers had been firing a constant hail of arrows at the defenders on the fortress walls. On 22 July Mehmet ordered an attack by his infantry, 150,000 strong, and when that was driven back he ordered another assault the following day, but that failed as well. Then at daybreak on 27 July the entire Ottoman army attacked the fortress, but the defenders once more drove them back.

The failure of this third attempt convinced Mehmet that Shkoder could not be taken by direct assault, and so he left a number of troops to continue the siege of the city, while he used the rest of his army to attack other Venetian-held fortresses in northern Albania. Mehmet sent Daud Pasha with the Rumelian troops to attack Zhabljak, on the northern shore of Lake Shkoder, while the Anatolian soldiers under Hadım Süleyman Pasha were to take Drisht (Drivasto), six miles east of Shkoder. Zhabljak surrendered with little resistance, while Drisht held out for sixteen days before it was taken by storm, whereupon its inhabitants were herded to Shkoder and beheaded in front of its walls to persuade the defenders there to surrender.

Mehmet then ordered Süleyman and Daud to attack Lezhe, where Skanderbeg had died in 1468, and after taking the town they burned it to the ground. They then went on to attack Bar, on the coast of what is now Montenegro, where the defenders under the Venetian governor Luigi da Muta put up such a determined fight that the Ottoman commanders finally abandoned the siege. Mehmet then ordered his army to withdraw from Albania, leaving enough troops behind with Evrenosoğlu Ahmet to continue the siege of Shkoder.

The Turkish raids in Friuli and the Ottoman advance in Albania, coming after sixteen years of warfare, finally convinced the Signoria to come to terms with Mehmet. The secretary of the Senate, Giovanni Dario, a Venetian who had been born on Crete, was sent to Istanbul late in 1478, empowered to make an agreement without receiving further instructions. The result was a peace treaty signed in Istanbul on 28 January 1479 ending sixteen years of war between the Venetian Republic and the Ottoman Empire. The Venetians ceded to the Ottomans Shkoder and Kruje in Albania, the Aegean islands of Lemnos and Euboea (Negroponte), and the Maina (Mani) peninsula in the south-west Peloponnesos. The Ottomans for their part agreed to return within two months some of the Venetian possessions they had taken in the Morea, Albania and Dalmatia. The Venetians promised to pay within two years a reparation of 100,000 gold ducats, agreeing also to an annual payment of 10,000 ducats for the right of free trade in the Ottoman Empire without import and export duties. Venice in return was allowed to maintain a

bailo

in Istanbul, with civil authority over Venetians living and doing business in the Ottoman capital. In addition, both parties were to appoint an arbiter to define the boundaries between the two states.