The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City (24 page)

Read The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City Online

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Rome

VESPASIAN, acquiescent senator and able general under Nero, led the AD 67 Roman counteroffensive in Judea designed to put down the Jewish Revolt. He too would become emperor of Rome. (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen)

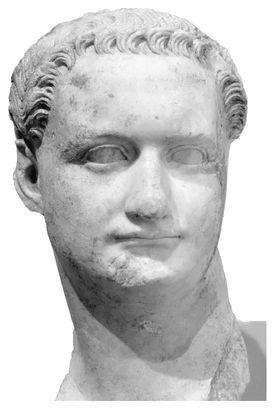

DOMITIAN, youngest son of the cash-strapped senator Vespasian, was a thirteen-year-old chariot-racing fan in AD 64. He would live to see his father, brother, and himself become emperor of Rome. (Capitoline Museum, Rome)

XVI

THE SUICIDE OF SENECA

E

arly this same day, April 19, the day that the chariot racing was due to take place in celebration of the Festival of Ceres, Lucius Seneca and his wife Pompeia Paulina traveled in from a country estate in Campania and arrived at the villa of one of Seneca’s friends—Novius Priscus, apparently—just four miles south of Rome. Joined by Seneca’s doctor, Statius Annaeus, the party prepared to spend the night at the villa.

arly this same day, April 19, the day that the chariot racing was due to take place in celebration of the Festival of Ceres, Lucius Seneca and his wife Pompeia Paulina traveled in from a country estate in Campania and arrived at the villa of one of Seneca’s friends—Novius Priscus, apparently—just four miles south of Rome. Joined by Seneca’s doctor, Statius Annaeus, the party prepared to spend the night at the villa.

That evening, Seneca, his wife, his doctor, and his host had commenced dinner when a large party of Praetorian soldiers came marching down the road from Rome and surrounded the house, having tramped for upward of an hour after leaving the capital. The detachment’s senior officers were on horseback. The officer in charge, the tribune Gavius Silvanus, dismounted and went inside the house to address the emperor’s questions to the former chief secretary. He found Seneca, his wife, and two friends in a dining room, spread on couches around a low dining table. Seneca had lost a great deal of weight since the tribune had last laid on eyes on him. “His aged frame,” said Tacitus, was “attenuated by frugal diet.”

1

Standing before the diners, Silvanus put his questions to the former chief secretary.

1

Standing before the diners, Silvanus put his questions to the former chief secretary.

“Yes, tribune, Natalis was sent to me,” the gaunt Seneca nonchalantly acknowledged in reply, leaning on one elbow with his wife reclining beside him, “and he complained to me in Piso’s name because I had refused to see Piso.”

2

2

The tribune asked why Seneca had refused to see Piso.

“I excused myself on the grounds of failing health and the desire to rest,” Seneca replied. “I had no reason for preferring the interests of any private citizen to my own wellbeing. I have no natural aptitude for flattery; no one knows that better than Nero, who more often experienced my outspokenness than my subservience.”

3

3

The tribune withdrew. Leaving his troops around the villa, Silvanus rode back into the city to report to the emperor. He found Nero at the Servilian Gardens, where the emperor was now accompanied by his wife Poppaea and Praetorian Prefect Tigellinus. The empress and the prefect had become, in this grave situation, “the emperor’s most confidential advisers,” said Tacitus.

4

4

After the tribune repeated Seneca’s answers to the questions put to him, Nero asked, “Was Seneca considering suicide?”

“No, Caesar,” Silvanus replied. “I saw no sign of fear, and perceived no sadness in his words, or in his looks.”

5

5

Nero deliberated with Poppaea and Tigellinus on what course to follow. Authors Tacitus and Suetonius were adamant that Nero wanted Seneca dead, fearing both his influence and his ability. Tigellinus would have reminded Nero that Seneca’s last words to Natalis incriminated him—the comment that his safety depended on Piso’s safety. This, the adviser would have said, proved that Seneca was aware of the assassination plot and the plan to install Piso in Nero’s place once the emperor had been murdered, but Seneca had not attempted to warn the emperor that his life was in grave danger from Piso. Even if Seneca had not been an active member of the conspiracy, his failure to disclose the plot to Nero represented treason.

“Inform Seneca that sentence of death has been passed on him,” Nero told Silvanus.

6

6

“Yes, Caesar.” The tribune hurried away to comply. But he did not return to the villa outside the city directly. Instead, in the summer twilight, Silvanus went to the second Praetorian prefect, Faenius Rufus, whose association with the conspiracy was still a well-guarded secret. Tribune Silvanus was also a party to the plot, having joined it during its second surge of recruitment, and was aware of Rufus’ involvement. Silvanus informed Rufus of Nero’s orders concerning Seneca and asked what he should do.

Rufus admonished the tribune for coming to him and instructed Silvanus to follow the emperor’s orders without further delay. Silvanus took his leave and set off back to the villa outside Rome, where he had left Seneca. Tacitus said of Rufus, Silvanus, and other Praetorian officers involved in the assassination plot: “A fatal spell of cowardice was on them all.”

7

Recording these happenings several decades later, Tacitus based his account, he revealed, on the writings of Fabius Rusticus, the historian who had been both a friend and a client of Seneca and who seems to have had particularly good contacts within the Praetorian Cohorts.

7

Recording these happenings several decades later, Tacitus based his account, he revealed, on the writings of Fabius Rusticus, the historian who had been both a friend and a client of Seneca and who seems to have had particularly good contacts within the Praetorian Cohorts.

Tribune Silvanus was mightily troubled by the turn of events. It would transpire that his fellow Praetorian tribune Sabrius Flavus, one of the originators of the assassination plot, had not been happy with the other conspirators’ choice of Gaius Piso as Nero’s replacement. In Flavus’ soldierly opinion, it was just as disgraceful to make a tragic actor emperor of Rome as it was to endure a harp player on the throne. Flavus had another candidate in line for the throne—Seneca. The tribune felt that Seneca was “a man singled out for his splendid virtues by all men of integrity” and would make a much better ruler than either Nero or Piso.

8

Seneca had experience in the job, after all, having been virtually a de facto emperor, ruling through Nero during the early years of the boy emperor’s reign. Flavus’ plan was to initially go along with the civilian conspirators, up to the point that Nero was slain. Flavus and several of his centurions, whom he had already brought into this subplot, would then murder Piso and hand the empire over to Seneca, who would take the throne as next emperor.

8

Seneca had experience in the job, after all, having been virtually a de facto emperor, ruling through Nero during the early years of the boy emperor’s reign. Flavus’ plan was to initially go along with the civilian conspirators, up to the point that Nero was slain. Flavus and several of his centurions, whom he had already brought into this subplot, would then murder Piso and hand the empire over to Seneca, who would take the throne as next emperor.

While this twist in the original plot had been inspired by Tribune Flavus, Seneca was apparently well aware of it. This was why he had come up to the house just outside Rome this day, to await news of Nero’s death, and of Piso’s death, and then to be conveyed to the Praetorian barracks and hailed as Rome’s next emperor. Tribune Silvanus was also aware of this plan, but with Nero still alive and with Prefect Rufus unwilling to show his true colors, Silvanus did not have the courage to set the plot in motion himself. Nor did he have the courage to face Seneca. After riding back to the villa and arriving after dark, the weak-kneed tribune instructed one of his centurions to go into the villa and inform Seneca of the death sentence passed on him by Nero.

Inside the villa, Seneca, his wife, and his friends had waited tense hours for this verdict to be delivered from the emperor, although it is likely that Seneca had guessed that his time was up, and he was only living in hope that the Praetorian officers involved in the conspiracy would declare their hands and set the plot in motion and complete Nero’s overthrow. The centurion who now delivered Seneca’s death sentence was not involved in the conspiracy and was loyal to Nero, and as far as the messenger was concerned, the old man before him was a convicted traitor. As the centurion spoke, his hand would have rested on the hilt of his sheathed sword, to emphasize both his capital authority and his mission.

“Will you allow me to have [wax] tablets brought in so that I might write my will?” Seneca asked him.

“No,” the centurion gruffly replied.

With a sigh, Seneca turned to his wife and friends. “As I’m forbidden to reward you, I bequeath you the only possession, but still the no-blest possession, that I am still able to give—the pattern of my life.”

9

9

Seneca had made a name for himself as a philosopher, particularly with his writings during his exile on Corsica. Many of his sayings have passed down to present day. Yet, Seneca had frequently failed to live up to the high standards he set in his own philosophy. Far from living a simple life, he had amassed great wealth, had lived in luxury, and had charged exorbitant rates of interest on the money he had loaned out. It was said that in summarily calling in his massive loans to British tribes in AD 59- 60, he had contributed to resentment in Britain that had led to Boudicca’s bloody revolt. He had been convicted of committing adultery with one daughter of Germanicus Caesar, Julia, and was accused of being the lover of another, Nero’s mother, Agrippina the Younger. A case can also be put that Seneca had even been involved in the murder of Germanicus, to win favor with Sejanus, Tiberius’ powerful and ambitious Praetorian prefect. And there was no denying that Seneca had colluded with Nero in the final stage of the murder of the young emperor’s mother and had orchestrated the subsequent cover-up. Blameless and virtuous his life had not been.

The pattern of Seneca’s life, then, was far from worthy of emulation. Yet, Seneca had come to believe his own publicity, which had been propagated during his years in power, and believed himself to be a man of splendid virtues. Like many sinners, he felt that in being sinned against, he was the victim. He seems to have genuinely believed that he was ending his life as a martyr to tyranny, even though he had for many years been the tyrant’s accomplice.

“If you remember it [the pattern of his life] after I am gone, you will win a name for your moral worth and steadfast friendship,” he grandly added.

10

10

Seneca’s wife and his friends were in tears. Paulina was much younger than her husband, possibly less than half his age. Seneca’s first wife and a young son, his only child, had died while he was in exile. Paulina, daughter of a former consul who was one of three men entrusted by Nero with the management of the public revenues, had been a loyal and loving wife to Seneca. Not long before this, Seneca had written as much to a friend: “She is forever urging me to take care of my health, and indeed as I come to realize the way her very being depends on mine, I am beginning, in my concern for her, to feel some concern for myself.”

11

11

Now, as tears flowed around him, Seneca urged his friends to dry their eyes and face what was to come with “manly resolution.” And then he rebuked himself for allowing matters to come to this. “Where are your maxims of philosophy, Seneca, or the preparation of so many years’ study against future evils? Who did not know of Nero’s cruelty? After murdering his mother and his brother, all that remains is to add the destruction of his guardian and tutor.”

12

12

The centurion, watching and listening to all this, would have impatiently patted his sword. He was under orders from his tribune to permit Seneca to take his own life, but there was a limit to his patience. As Seneca embraced the sobbing Paulina, “he begged and implored her to spare herself the burden of perpetual sorrow.” She should instead, he said, console herself with remembrances of the virtuous life they had spent together.

13

13

It was clear that Seneca intended to commit suicide, despite the fact that he had recently written to a friend, “A good man should go on living as long as he ought to, not just as long as he likes. The man who does not value his wife or a friend highly enough to stay on a little longer in life, who persists in dying in spite of them, is a thoroughly self-indulgent character.”

14

But the situation he now found himself in made a self-induced demise a more attractive prospect. Few Romans declined the opportunity to take their own lives rather than submit themselves to the executioner once they had been condemned to death. More than a fear of the pain of decapitation, these men took the option of suicide because their fate was still in their own hands to the end, whereas with execution as a bound prisoner, their fate was surrendered to another. This was why Romans considered suicide, far from being a crime, an honorable act.

14

But the situation he now found himself in made a self-induced demise a more attractive prospect. Few Romans declined the opportunity to take their own lives rather than submit themselves to the executioner once they had been condemned to death. More than a fear of the pain of decapitation, these men took the option of suicide because their fate was still in their own hands to the end, whereas with execution as a bound prisoner, their fate was surrendered to another. This was why Romans considered suicide, far from being a crime, an honorable act.

Out of the blue, Seneca’s wife announced, “I too have decided to die.” She looked at the now startled Praetorian officer. “Take off my head, centurion.”

The centurion responded that he had no orders regarding her execution and could not oblige her.

Other books

The Silken Edge (Silken Edge 1) by Paige, Laci

Healing (General's Daughter Book 5) by Breanna Hayse

Best Friends With Benefits (Most Likely To) by Candy Sloane

Starfist: A World of Hurt by David Sherman; Dan Cragg

Breaking the Line by David Donachie

Unraveled by Sefton, Maggie

Her Counterfeit Husband by Ruth Ann Nordin

The Necromancer by Scott, Michael

Las Montañas Blancas by John Christopher