The Greek Islands (24 page)

Authors: Lawrence Durrell

Some of the monks are ex-brigands – it is (or was) a

convention

in Greece that brigands, when they are getting on and have no pension, abruptly repent and become monks of great

splendour

. In most monasteries there is a brigand picture taken in the good old days when the ambushes and purse-slittings were good. The transformed brigand often has it framed and hung on the walls of his cell. I have seen a dozen of these pictures in various places in Greece, and the posture of the band has some of the diffident solemnity of a football eleven of adolescents. The camera has only recently been accepted in Greece; in the thirties it was widely regarded as a machine for casting the Evil Eye on people who were unwary enough to allow their souls to be snatched by the contrivance. I remember a group of monks on Mount Taygetus in Laconia running for shelter and ducking behind a rood screen as I unleashed my old Rolleiflex. After the last war, the superstition was conquered, and everywhere I was badgered by people – especially monks – to take their photographs. But some of the old fear still exists in the remote

villages of Crete, where a peasant woman will shield her face, or else, having been snapped, will spit into her breast and repeat the magic formula against bewitchment. In the last century, before the daguerreotype was invented, draughtsmen who wanted human portraits ran into this problem in Greece, though it was not perhaps so ingrained here as in Moslem countries. Now you even meet people who have been

photographed

with Sophia Loren – which they rightly remember as a great event.

One of the great tragic events of the modern history of Chios is the massacre of 1822, which inspired some of Victor Hugo’s choicest rhetoric and a magnificent picture by Delacroix, a copy of which is to be found in the museum. The little islet of Psara, which lies quite near, was similarly devastated by the Turks and inspired a lapidary poem by Solomos, who wrote the national anthem for the Greeks. The two most uplifting and noble national anthems are the Greek and the French, which embody the feelings of an entire epoch and a whole race. Other national anthems seem dead by comparison. Listen to the Greek one sung with the words. The only song in English which

comparably

ignites the heart and uplifts the soul is the Blake oratorio ‘Jerusalem’. Even Mozart could do nothing memorable with ‘God Save the King’, though he meant to pay a compliment, for he admired England (because of Hume).

The history of Chios is not significantly different from that of the neighbouring islands. The same succession of piratical nations have held it, alternatively sacking it or securing for it a few years of peace and prosperity. For such a pretty island, it is odd that its image is more industrial than romantic. You feel that both Samos and Chios were always stepping-stones to the continent; even in winter, they were not blocked up by heavy seas as the central group of Cyclades are even to this day. They traded in winter; and of course once on the mainland, the

islanders easily touched the tail end of the spice routes and the caravan highways to India. Hence a certain sophistication of outlook, which they shared in ancient times with Lesbos. Nowadays, the rich absentee landlords prefer Paris or London as a place of residence; but summer brings them back.

In its respect for the seasons the pattern of Greek life is constant. Families, even in ancient times, possessed a little house or a big property by the sea. Here they set up shop for the sunny weather, held court and invited all their friends and their children. I remember one holiday on an island, where I had arrived with letters of introduction to an old lady of wealth and distinction, an obscure, Venetian countess who still guarded her long-extinct title. The family was just loading up to go to the summer property which lay on the other side of the island. I was at once invited to join them – a merry band of cousins and aunts and uncles, with their children, and hampers loaded with enough food to sink a ship. The setting-off was impressive. Seven or eight

fiacres

or gharries were lined up at the door and solemnly loaded with all that might be necessary for three or four months’ stay on the other side of the island. The country property was a fine, unkempt old villa with wrought-iron gates which squeaked abominably; it was pitched on a headland above a lion-coloured beach. Two mad monks were the

caretakers

, one deaf and one lame; they fed the pigeons and kept the hunting dogs in trim.

I set off with my hosts – the long line of

fiacres

raising a white plume of dust along the white roads. The trip took about two hours, not more. We moved like a column of infantry, with the old lady in the leading

fiacre

. We were waved goodbye by the grandmother, who had supervised the loading with great care, standing on the steps clicking the house-keys in her hand and admonishing, criticizing, or praising. (She kept the

food-cupboards

well locked and every morning dished out supplies

for the day.) The grandmother was staying behind but would be coming over to join us and take up her family duties in the other house within a couple of days. The baggage-train

contained

everything necessary for the family’s health and

well-being

in the weeks to come – toys, pets, nannies, cutlery, pots and pans, phonographs, a boat, easels and colours, and even a small upright piano, which occupied a

fiacre

to itself and jogged contentedly along behind the column uttering from time to time a plangent whimper. (On the morrow a piano-tuner would ride across the island and set it to rights in its new abode.)

By the time we arrived, the country house had been

reactivated

, for the servants had walked across the island during the night and warned the mad monks. The rooms had been opened up and aired, beds made, staircases dusted, gutters, swollen with winter leaves, unplugged. Even the beds were made, with fine old linen sheets which smelled of lavender, and the dusty mirrors cleaned and angled. There had also been a huge delivery of ice-blocks, which were stacked in the

improvised

freezer – a sort of underground room or crypt, whose walls were insulated with the pulped flesh of the prickly pear. (For ordinary daily purposes, wine and butter were simply put down the well in a hamper.) Meanwhile, way below, in the sunken garden full of delightfully bad statuary, the blue sea prowled and sighed, impatiently waiting for its children and their boat.

The form of this summer migration has varied little throughout the centuries, though of course some details are different (today, for example, there is a refrigerator, either

electric

or, for remoter places, paraffin-operated). When you read of Nausicaa playing ball on the beach and discovering the naked Odysseus in the bulrushes, or of Sappho going into the country with her maids, this is the sort of background to

events. No piano, of course, but Sappho would have taken the harps and lutes necessary for her summer symposium, including the little one she invented.

The tradition, however modified, will continue, one feels, as long as the Greek summer remains what it has always been – hot, dry, touched by the island winds at sunset, and then

cool-to

-cold at night, with a sky of such clear brilliance that you can lie for hours watching it breathe, counting the shooting stars as they cross and recross the darkness, and then watching the Pleiades rise like the tiny horns of new born lambs or the first flowers opening upon the spring. On such occasions, one is aware of the big silences of the philosophers whom we have followed but never superseded, those men so deeply conscious of the slow-burning fuse of death which invisible fingers had lighted on their first birthday.

In the town, you never forget the presence of the mainland – the grim promontory of Karaburna – a name like a drumbeat – which faces you across the blue water. In ancient times, Chios must have seemed a haven of civilization and comfort lying just within the shoulders of the shaggy-bear continent of

Anatolia

. It is still rather like that today, and will be so until the Greeks and Turks decide to become good neighbours and indispensable friends.

In islands like these, one mentally thinks back to visitors who have already been here and left us a record of their impressions; sometimes they were not poets but business men or sedate travellers moving about for their health. All such impressions are precious, for they mark the passage of time for us. An example is that fabulous globe-trotter Lithgow who, after almost twenty years of trotting, left a monumental record of his journeys – as invaluable as it is lively, though there is not much humour in it.

The Total Discourse of the Rare Adventures of William Lithgow

is a great travel book, written with pain and

conscience, and providing a graphic account of travel in the Mediterranean during the seventeenth century. Himself rather a curious bird, Lithgow had every reason to stay abroad and indulge an induced perambulatory paranoia. He was caught behaving in an undeclared, amorphous manner with a pretty village girl who unfortunately had five disapproving brothers. In their quiet, undemonstrative, Scots way they lopped his ears and drove him from the parish to bury his humiliation in

foreign

parts. The locals called him ‘cut-lugged’ because of his cropped ears. Shame drove him to travel. One always thinks of him in Chios because he has left us a description of the island, whose women, he avers, are of exceptional beauty: ‘The women of the city of Scio are the most beautiful dames or rather Angelical creatures of all Greeks upon the face of the earth, and greatly given to venery. Their husbands are their panders, and when they see any stranger arrive, they would presently demand of him whether he would have a mistress; and so they make whores of their own wives.’ Although this may well have been true in the seventeenth century, it is difficult to imagine in the sedate Chios of today. There are a few nightclubs here and the sort of night-life which in its modest way attracts Nordic tourists – and why not, when the nights are so fine and crystal clear, and the sky like old lace? It seems a crime to go to bed early in Greece, and even the little children are allowed up very late, so that when they turn in they really sleep a dead-beat sleep, instead of spending the night whining and sucking their thumbs as so many northern children do. All habits, of course, stem from climate which, in a subtle, unobtrusive manner,

dictates

everything about the way we live, and often about the way we love.

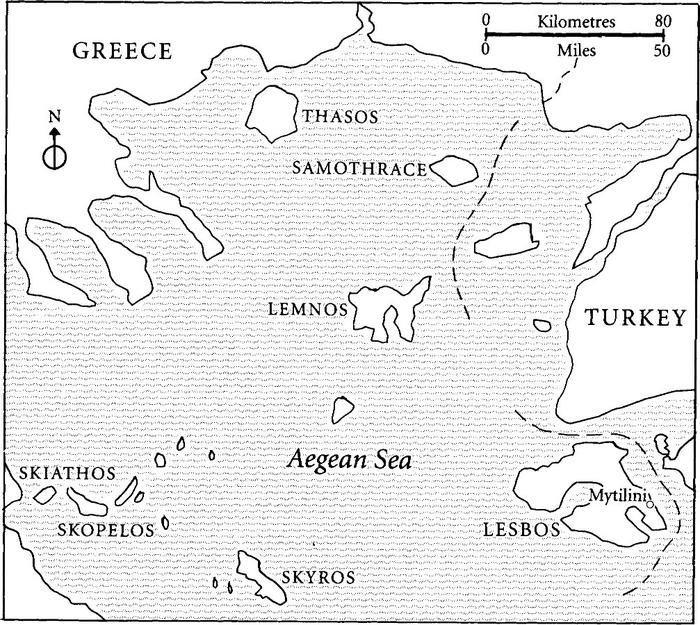

Spacious and gentle is Lesbos â but how to escape from the net of ancient associations which make everything to do with the place memorable? But then, why try? Lesbos vibrates like a spiderweb with the names of high antiquity â the greatest of all being Sappho. Here, in the shadow cast by slate-grey Olympus, Sappho lived and worked, though, if Eressos is really her native hamlet, she worked with her back to the present Turkish

mainland

. In contrast, the modern capital of Lesbos, Mytilini, which is perched on its long irregular promontory in the eye of the wind, faces the mountains across the water. A glance at the map will show how queer its shape is â like a half-enunciated

geometrical

problem. Its lozenge form is abruptly carved into by two great landlocked bays, Kalloni and Iera, the former nearly ten miles long, a haven of clam water to delight the heart of a sailor. Each of these natural estuaries has a narrow entrance drilled like a sinus into the landscape. Entering them, you receive your first impression of Lesbos as a place offering

tranquillity

and beauty and a sort of repose which seems even to silence the

cicadas

at noon. Perhaps this impression is the result of finding such safe anchorages, where one can sleep on deck under the stars, conscious of rich glades close by, which are densely clothed in olives as hairy and untutored as those of Corfu. Lesbian fruit and olives find their way to the Athens market; so do the Lesbian

ouzo

and white wine.

Mytilini is a breezy and pleasantly animated little township without any special, awesome antiquities, and just a sufficiently

mixed style of architecture to divert the traveller. It is cool in summer because of its orientation; but the whole island has a singular charm which is hard to analyse since Lesbos is not as beautiful as Rhodes or Crete or Corfu. Is one being seduced by the literary association connected with its famous name? Even if I am accused of romancing I would say âNo', and insist that Lesbos belongs to a special category of place which holds a secret magic of its own. No matter how shattered by tourism or despoiled by promoters' taste, these select places (even if they are mere holes in the ground) still echo with a sort of message that the visitor receives. âOnce a star, always a star,' says Noël Coward very rightly. There is a radiance and a throb in names like Taormina, Avignon, Delos, Tintagel, Mycenae, which will never be extinguished â or so one hopes. I would put Lesbos into this category even though it is outclassed in natural beauty by other and bigger islands to the south and east. It is hard to describe the scenery objectively when one knows that for

Daphnis and Chloe

, that delightful novel, this place was chosen as a stage for its young lovers to walk, bemused in the

passionate

self-discovery that first love brings and time will never repeat. The subject matter of the book is divine innocence and pure joy â for which Greece provides an appropriate backcloth; these vernal glades and combes with their fruit-blossom, oleanders and olives is the perfect setting for such a theme.

If I turn away from Sappho for the present, it is to remind myself that in the long scroll of Lesbian history her name is only one of many illustrious names. Pittacus, tyrant of the island, was among the Seven Sages of Greece and enunciated the two brief maxims which were inscribed upon the porch of the Delphic temple. Theophrastus, who lived to be 107 years old, and spent thirty-five years as the head of the Athens

Academy

, was a pupil of Plato and Aristotle; his long reign shows him to have been justly popular in an epoch marked by political

and intellectual upheavals. Among philosophers and moralists who lived on the island were Aristotle, who taught here for two years, and the sadly neglected and traduced Epicurus, whom we are just beginning to appreciate at his true worth once more. Epicurus's philosophy exercised so widespread an influence that for a long time it was touch-and-go whether Christianity might not have to give way before it. But the poor in heart won out, don't ask me why â it is one of the great mysteries of the world. The Lesbian intellectual was held in high esteem in the ancient world. There is an anecdote about Aristotle appointing a successor to a teacher in his school. The choice lay between Menedemus of Rhodes and Theophrastus of Lesbos. The great Athenian philosopher deliberated long, and finally asked for the wines of the two islands to be served to him; he sipped them as he reflected. Then, pronouncing them both excellent, he gave the palm to the Lesbian, saying that it had more body. So Theophrastus was chosen for the post.

Plutarch has told us how famous the island already was in antiquity both for its musicians and for its poets; and the musical tradition was emphasized in mystical fashion by the fact that here the singing head of Orpheus was washed up and recovered after the Bacchantes had tossed it into the River Hebros. The famous âdolphin-charming' Arion was a native of Methymna (now Melyves), and Terpander of Lesbos was the first to string the lyre with seven strings â an invention which for the ancient world was as decisive as the jump from

clavichord

to piano was for us. (Sappho went so far as to invent her own small version of this lyre, upon which she accompanied herself.) The opulence of Lesbos's intellectual history is matched only by the opulence of its soil, and even today you can sense this. It would be a good place to work in, and quite a number of modern writers have been sufficiently impressed to spend a year or two in the island composing their books.

Lesbos has known nothing but the best in poetry, music and philosophy â a very rich heritage for one small place!

Its geographical strangeness also plays a part, for as you enter the narrow gullet of Iera or Kalloni the fissure closes behind you, sealed by the turning mountain. You lose sight of the

narrow

channel by which you have entered this anguish of silence and calm; a sense of unreality supervenes and you feel panicky.

Sappho is beginning to emerge from the haze which the dark ages cast over her. For a long time she seemed almost a mythical figure, perhaps some escaped Olympian, footloose on earth. Now we know that she was a real person and are gradually finding out more about her. Even her work is slowly coming to light, though we still have only about one-twentieth of what she actually wrote. For a long time this venerated ghost of antiquity existed only by hearsay and the chance quotation of phrases from her poems which were embalmed in the work of critics and grammarians. From these crumbs it was hard to show

convincing

evidence of her genius, and the few biographical

anecdotes

were either vague or implausible. Between 1897 and 1906, however, by a stroke of luck, at a place in Egypt called

Oxyrhynchus

, a great find was made by the scholars of the Egypt Exploration Society.

The sand is a wonderful preserver of objects and writings, and the find consisted of a hoard of mummy-wrappings

fabricated

from papyrus. These writings, presumably regarded as expendable by their owners, were used as wadding for coffins, or even as stuffing for ritually embalmed animals like small crocodiles. They ranged in period from the first century

BC

to the tenth

AD

. All this workshop rubbish had been thrown on to a garbage-tip, from which the scholars managed to rescue it. Among so many ancient texts, quite a number were Sappho's poems. Our earliest papyrus is from the third century

BC

, some three hundred years after her death â though there is one small

piece of pottery inscribed in a fourth-century hand. At the time of writing, however, not everything has been deciphered and released, so some new poems may yet emerge. Her great

popularity

in the lands where Greek was spoken ensured that her texts were jotted down by many different hands â which provides a fertile field for scholars of variant readings.

If we are to trust reports she was small and swart, and was compared to the nightingale, which is a particularly ugly little bird. âSmall and dark, with unshapely wings enfolding a tiny body'; this was the poetess whom Plato called the Tenth Muse. The little portrait of her â made long after her death â on the red-figured hydria by Polygnetus, which is in the National Museum of Athens, depicts a slender woman with a

disproportionately

big head and a long, reflective nose. She might be the sister of Virginia Woolf, so close is the resemblance.

Her poems were accessible to everyone; they were not

alembicated

and difficult. Moreover they were sung or danced or mimed before the general public. So great was their simple and vehement force that their author was treated almost as a

goddess

and statues to her were erected all over the civilized world. More than a thousand years of ancient testimony â 600

BC

to

AD

600 â insisted that she was the greatest poetess the world had ever known. Then a chill wave of doubt and sanctimoniousness set in and gradually her work was almost totally destroyed, while allegations as to her sexual proclivities began to be bandied about, largely under the influence of Ovid's satyrical allusions.

Born in 615

BC

, Sappho was married to a rich businessman from Andros, who, however, is not mentioned in any of the fragments of her verse which we have today. That she was wealthy and from an aristocratic background there seems little doubt. She presumably played her part in the political life of Lesbos, for twice she was banished. She seems to have travelled

a good deal in Greece, and to have made a great impression on the celebrated men she met; Alcaeus, her contemporary, called her âpure and holy Sappho', which has prompted the great scholar C. M. Bowra to speculate on whether she was the prime mover in a

Thiases

or semi-religious college of women centred upon the cult of Aphrodite and the Muses. Priestess, director, and living muse, she marshalled her group of girls and

organized

the celebrations which marked the seasons. Looking back from today, it is hard to realize how much this old religion formed part and parcel of the Greek corpus of belief.

I suspect that Greek religion, looked at through the smoked glasses of Pauline Christianity, shows a somewhat distorted

version

of itself. But in a world where the gods meddled so actively in the life of men, and where men could actually celebrate a ritual marriage with a goddess, the effective life of the ordinary people must have been vastly different from our own. You never knew, when there was a knock on the door, whether it was Aphrodite herself in human form outside. Often it was; though you did not usually realize this until after she had gone. Man's soul moved easily between earth and sky, and it is not really possible for us to appreciate the sort of religious considerations which dictated the ancient Greek's order of priorities. Today, it is only the poets who have not lost the faculty of sensing the Aphrodite under the disguise of an old shepherdess or a wrinkled crone. It is likely that the Greeks had developed

different

faculties of awareness from our own â an immediacy of recognition of things cosmic, or even of states like death. Conversely, they would have found it impossible to read St John of the Cross without amazement and perhaps disgust; and a crucifix would have taken some understanding, even though they were cheerfully accustomed to animal-sacrifice in the name of one of their gods. One has to keep all this in mind when trying to feel one's way into the hearts and minds of

ancient peoples. As for Sappho, how much was she goddess and how much poet? We shall never perhaps know. But that she was very much a woman, and a passionate one to boot, there seems little doubt from the poems we have of hers.

One senses, too, what it was in her attitude which struck such a chord in the heart of the whole civilization which bore her. The poetry was at once fine and energetic as a vision of her feelings; people found it unusual, in an epoch of classical

invocation

to abstract personifications, to come upon verse which was in touch with the universal as well as commonplace

emotions

like vexation, passion, pathos, desire. A whole personality was actualized in her work; hers was not simply a superlative but frigid technique. An original and unexpectedly touching person emerges from the supple verses, from the music. That is why old Strabo calls her âa miracle of a young woman', and that is why the older Solon admired her. I think too that it is fair to sense behind this praise an acceptance of her moral excellence as a muse and earth representative of Aphrodite. There is, at any rate, no suggestion of lubricity or impropriety in private

conduct

in these early references â whatever the state of morals in Lesbos at that time. The suggestions of lesbian predispositions and illicit loves come later from Ovid; but even he goes back on them, and says that she lost her taste for girls by falling in love with a man. What does it all matter?

There is no reason to doubt the popular story of her death, though serious scholars have always treated it as intrinsically improbable. Why? She followed a lover, Phaon, through the islands and, when he refused her love and left her, jumped from the White Cliff in Lefkas to her death. She would have been about fifty, for in a fragment she mentions her wrinkles and the fact that she is past the age of child-bearing. The visitor to Lesbos will find such tales as this one of her death, and the problems they raise of truth or legend, tease his mind, whether

he is travelling across the jade water of Iera at sunset with the slither of flying fish at his prow, or whether tucked against a tavern wall at Castro in Mytilini â a wall which shelters him from the wind, as he watches the shadow-play of vine-leaves upon the courtyard walls of the pink, blue and white houses of the town. There have been some digs at Eressos, her home town, but nothing really spectacular has been uncovered which might serve as a link with the forgotten epoch when Lesbos was one of the most civilized islands of the Greek archipelago.